November 1, 2015

◆

Volume 92, Number 9 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 807

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is a time-limited, goal-oriented psychotherapy that has been extensively researched

and has benefits in a number of psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder,

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, obsessive-compulsive and tic disorders, personality disorders, eating

disorders, and insomnia. CBT uses targeted strategies to help patients adopt more adaptive patterns of thinking and

behaving, which leads to positive changes in emotions and decreased functional impairments. Strategies include iden-

tifying and challenging problematic thoughts and beliefs, scheduling pleasant activities to increase environmental

reinforcement, and extended exposure to unpleasant thoughts, situations, or physiologic sensations to decrease avoid-

ance and arousal associated with anxiety-eliciting stimuli. CBT can be helpful in the treatment of posttraumatic stress

disorder by emphasizing safety, trust, control, esteem, and intimacy. Prolonged exposure therapy is a CBT technique

that includes a variety of strategies, such as repeated recounting of the trauma and exposure to feared real-world situ-

ations. For attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, CBT focuses on establishing structures and routines, and clear

rules and expectations within the home and classroom. Early intensive behavioral interventions should be initiated in

children with autism before three years of age; therapy consists of 12 to 40 hours of intensive treatment per week, for at

least one year. In many disorders, CBT can be used alone or in combination with medications. However, CBT requires

a significant commitment from patients. Family physicians are well suited to provide collaborative care for patients

with psychiatric disorders, in concert with cognitive behavior therapists. (Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(9):807-812.

Copyright © 2015 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

Common Questions About Cognitive

Behavior Therapy for Psychiatric Disorders

SCOTT F. COFFEY, PhD, and ANNE N. BANDUCCI, PhD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi

CHRISTINE VINCI, PhD, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas

C

ognitive behavior therapy (CBT)

is a group of time-limited, goal-

oriented psychotherapies that have

been extensively researched for the

treatment of psychiatric disorders. CBT tar-

gets changes in symptoms of psychiatric dis-

orders to reduce functional impairments and

improve patients’ overall quality of life. This

article aims to provide a concise overview of

CBT, including the types of disorders it can

treat, how it can be combined with pharma-

cotherapy, and how family physicians can use

CBT principles in their practice.

Which Patients Benefit from CBT?

CBT is effective for the treatment of anxiety,

depression, posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity dis-

order (ADHD), autism, obsessive-compulsive

and tic disorders, personality disorders, eat-

ing disorders, and insomnia. CBT-based

treatments for specific disorders are avail-

able at http://www.abct.org/Information/

?m=mInformation&fa=FactSheets.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

CBT effectively targets symptoms of anxiety,

1-4

depression,

5-7

PTSD,

8,9

ADHD,

10,11

autism,

12,13

obsessive-compulsive and tic disorders,

14

personality disorders,

15,16

eating disorders,

17

and insomnia

18

in children, adolescents, and

adults. Numerous meta-analyses and reviews

have demonstrated that CBT reduces psychi-

atric symptoms and functional impairments,

and improves quality of life.

1-18

The Ameri-

can Psychological Association lists CBT as an

effective treatment for numerous disorders.

19

Moreover, CBT has been shown to be as effec-

tive as or more effective than medications

for depression, anxiety, and trauma-related

disorders,

5,9,20-29

and it is a useful adjunctive

therapy for disorders such as ADHD, schizo-

phrenia, and bipolar disorder.

10-12,22,23

How Does CBT Work?

According to the cognitive behavioral model,

psychopathology occurs because of problem-

atic patterns in thinking and behavior that

lead to difficult emotions and functional

CME

This clinical content

conforms to AAFP criteria

for continuing medical edu-

cation (CME). See CME Quiz

Questions on page 764.

Author disclosure: No rel-

evant financial affiliations.

▲

Patient information:

A handout on this topic,

written by the authors of

this article, is available at

http://www.aafp.org/afp/

2015/1101/p807-s1.html

Downloaded from the American Family Physician website at www.aafp.org/afp. Copyright © 2015 American Academy of Family Physicians. For the private, noncom-

mercial use of one individual user of the website. All other rights reserved. Contact copyrights@aafp.org for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

808 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 92, Number 9

◆

November 1, 2015

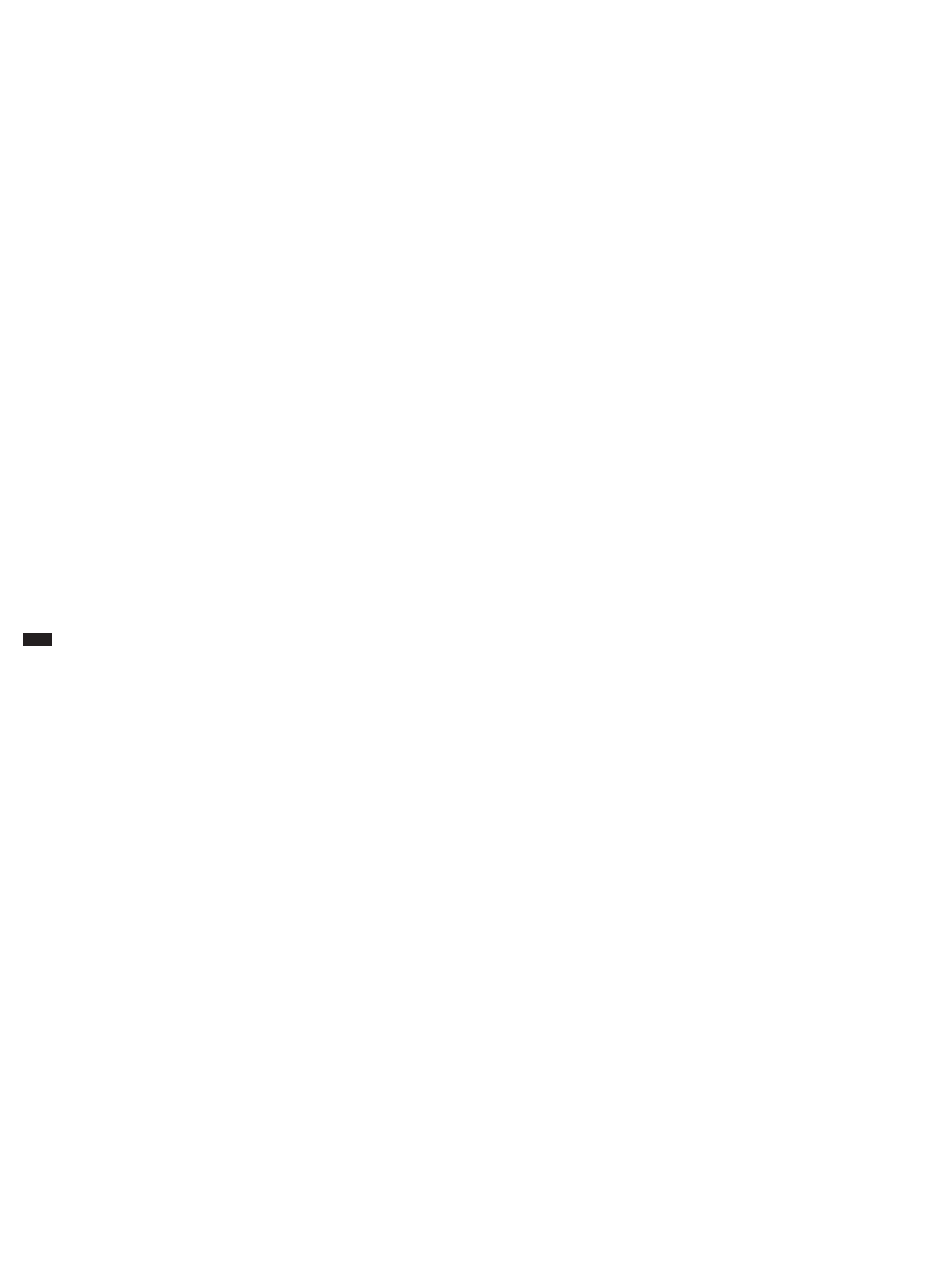

impairments (Figure 1). The aim of CBT is to help patients

adopt more adaptive patterns of thinking and behavior

to improve function and quality of life. Treatment goals

are selected collaboratively with patients to determine

whether progress is being made. CBT involves three core

strategies applied alone or in combination, depending

on the patients’ needs: (1) identifying and challenging

problematic thoughts and beliefs, with the goal of help-

ing patients develop more realistic and adaptive thoughts

and beliefs, (2) scheduling pleasant activities to increase

environmental reinforcement, and (3) extended exposure

to unpleasant thoughts, situations, or physiologic sensa-

tions to decrease avoidance and arousal associated with

anxiety-eliciting stimuli.

30

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Research demonstrates that problematic patterns of

thinking and behavior underlie most forms of psychopa-

thology.

30

Behavioral change has been shown to lead to

cognitive changes, and vice versa; these changes lead to

reductions in psychopathology.

5,6

How Does CBT Improve Depression?

A cognitive behavior therapist whose patient

feels sad and hopeless might choose to tar-

get the patient’s maladaptive thoughts (“I

cannot connect with anyone.”) or behaviors

(isolating and watching television). Targeting

changes in either domain leads to changes in

the other and in the patient’s emotions.

5,6

For

example, the therapist might challenge the

patient’s thoughts by eliciting examples of

occasions when the patient was able to posi-

tively engage with others. This could cause

the patient to feel less hopeless as he or she

realizes that the thought was not accurate,

and to call a friend to reconnect. Alterna-

tively, the therapist could attempt to change

the maladaptive behaviors by helping the

patient schedule pleasant activities consistent

with his or her values (calling a friend). This

reconnection could boost the patient’s mood

and change the belief that he or she will

SORT: KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Clinical recommendation

Evidence

rating References

CBT is an effective treatment for mild to moderate depression, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic

stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive and tic disorders, autism, eating disorders, personality

disorders, insomnia, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

A 1-18, 34-37

Psychiatric medications are the primary treatment for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but CBT

provides additional benefits.

B 22, 23

For many psychiatric conditions, CBT provides similar outcomes or additional benefits compared

with psychiatric medications alone.

A 5, 9-11, 18, 20,

22, 24-27

Benzodiazepine use should be avoided in patients who are receiving CBT because it can interfere

with exposure therapy.

C 38-41

CBT = cognitive behavior therapy.

A = consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence; B = inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence; C = consensus, disease-oriented

evidence, usual practice, expert opinion, or case series. For information about the SORT evidence rating system, go to http://www.aafp.org/afpsort.

Figure 1. The cognitive behavioral model illustrates problematic pat-

terns in thoughts and behaviors that lead to emotional difficulties

and functional impairments.

Cognitive Behavioral Model

Thoughts (e.g., “I cannot

connect with anyone and

will always be alone.”)

Behaviors (e.g.,

isolating, watching

television, overeating,

using substances)

Feelings (e.g., sadness,

loneliness, angry at self)

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

November 1, 2015

◆

Volume 92, Number 9 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 809

always be alone. Although these examples

misrepresent the amount of therapeutic work

needed to change entrenched patterns of

thoughts and behaviors, they give a sense of

what the therapeutic process might involve.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

CBT can be used to reduce symptoms

of depression, with or without medica-

tion.

5-7,20-29,31-33

Although treatment guidelines

from the American Psychiatric Association

suggest that medication should be used as a

first-line treatment for depression, CBT should

also be considered. Evidence has shown that

CBT and paroxetine (Paxil) produce equivalent outcomes

in patients with severe depression.

34

Thus, family physi-

cians must use their clinical judgment in determining

which treatments to suggest for their patients.

How Does CBT Improve Anxiety and Trauma-

Related Disorders?

Similar to the example above, therapists who are treating

patients with anxiety and trauma-related disorders chal-

lenge problematic patterns of thoughts or behaviors. A

more thorough description of CBT for PTSD is provided

here as an example.

Evidence-based therapies for PTSD in adults include

cognitive processing therapy and prolonged expo-

sure therapy, whereas trauma-focused CBT is used in

younger patients. Cognitive processing therapy includes

psychoeducation about PTSD and focuses on challeng-

ing maladaptive thoughts and beliefs about safety, trust,

control, esteem, and intimacy.

35

Prolonged exposure

therapy includes psychoeducation about PTSD, breath-

ing retraining to decrease arousal, repeated recounting

of the trauma to teach patients that the memories are not

dangerous and do not need to be avoided, and in vivo

exposure to feared real-world situations.

8,9

In younger

patients, trauma-focused CBT includes components

similar to those for prolonged exposure and cognitive

processing therapies, but also includes parallel and joint

parental sessions.

36

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

CBT techniques for the treatment of PTSD can be

applied across all anxiety and trauma-related disorders

in children, adolescents, and adults.

1-3,35-37

Is CBT Different When Used in Children vs. Adults?

Parental involvement in therapy is necessary when chil-

dren receive CBT. Parents can ensure that their child

engages in behavioral exercises between therapy sessions

(e.g., in vivo exposures, pleasant activities), can change

the child’s environment to promote more effective

behaviors, and can help the child target changes in mal-

adaptive thoughts. In general, CBT for children focuses

more on behavior changes and less on cognitive changes.

Behavioral techniques used for children with ADHD and

autism are described below.

ADHD

A recent review showed that behavioral parent training,

behavioral classroom management, and behavioral peer

interventions are well-established treatments for ADHD.

11

Behavioral parent training and behavioral classroom

management focus on strategies implemented by adults

to help children with ADHD function more effectively,

including creating structure and routines, setting clear

rules and expectations, using effective commands, and

rewarding or punishing the child based on his or her com-

pliance. These techniques help reduce behavioral prob-

lems experienced by children with ADHD and decrease

the need for polypharmacy to manage symptoms.

11

AUTISM

Early intensive behavioral interventions are the only

evidence-based treatment that confers significant bene-

fits in children with autism.

12

These interventions should

be initiated before three years of age and often consist

of 12 to 40 hours of intensive treatment per week, for at

least one year. Parents and therapists engage in intensive

exercises focused on reinforcing and rewarding adaptive

behaviors. Behavioral treatments for autism produce sig-

nificant improvements in IQ and adaptive behaviors.

13

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Behavioral therapy is the only effective treatment for

autism

12

and is an important adjunctive treatment for

BEST PRACTICES IN PSYCHIATRY: RECOMMENDATIONS

FROM THE CHOOSING WISELY CAMPAIGN

Recommendation Sponsoring organization

Avoid use of hypnotics as primary therapy for

chronic insomnia in adults; instead, offer

cognitive behavior therapy, and reserve

medication for adjunctive treatment when

necessary.

American Academy of

Sleep Medicine

Do not prescribe medication to treat childhood

insomnia, which usually arises from parent-

child interactions and responds to behavioral

intervention.

American Academy of

Sleep Medicine

Source: For more information on the Choosing Wisely Campaign, see http://

www.choosingwisely.org. For supporting citations and to search Choosing

Wisely recommendations relevant to primary care, see http://www.aafp.org/afp/

recommendations/search.htm.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

810 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 92, Number 9

◆

November 1, 2015

ADHD.

10,11

In addition, CBT provides substantial ben-

efits for children with depression or anxiety.

3,7

Is CBT Effective for Other Disorders?

CBT has been examined and tested across a wide range

of psychiatric disorders. In addition, it has been exam-

ined as an adjunctive treatment for medical problems in

which behavior change could enhance outcomes.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Although a thorough discussion of the effectiveness of

CBT for all psychiatric disorders is beyond the scope of

this article, it has been shown to have significant benefits

for patients with insomnia,

18

psychosis,

23

bipolar disor-

der,

22

eating disorders,

17

and personality disorders.

15,16

Family physicians are encouraged to seek adjunctive

CBT for patients diagnosed with these disorders.

When Can CBT Be Combined with Medications?

CBT can be used alone or in combination with medica-

tions for a variety of psychiatric disorders. Medications

can be used to stabilize patients and promote recov-

ery, whereas CBT can be used to encourage long-term

changes in thoughts and behaviors.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

CBT generally produces equivalent outcomes or provides

additional benefits compared with the use of psychiatric

medications alone.

5,9,12,20-23,26,34

Moreover, CBT is often

more cost-effective, has more enduring effects,

9,21-23,27,28

and lacks the adverse effects associated with many psy-

chiatric medications. The effects of CBT are reduced in

patients who are receiving benzodiazepines

38-40

; there-

fore, these medications should be avoided in patients

with anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Although a

combination of CBT and benzodiazepines may initially

seem beneficial (e.g., reduced arousal, improved sleep),

this approach may actually limit the gains made with

CBT (e.g., patients may not be able to engage in exposure

exercises when arousal is reduced as a result of medica-

tion use).

38,41

What Are the Potential Limitations of CBT?

CBT is most effective when patients complete therapeu-

tic exercises outside of the treatment session; therefore,

it requires a significant commitment from patients.

Some of the therapeutic strategies may involve anxiety-

eliciting stimuli, which can be distressing—although

short-lived—for some patients. The structured nature of

CBT is not a good fit for patients who are seeking insight

into the underlying causes of their distress. Lastly, CBT is

not a substitute for pharmacotherapy for some disorders.

For example, CBT should be considered an adjunctive

treatment in the management of bipolar disorder, psy-

chotic disorders, and depression with psychotic features.

How Can Family Physicians Integrate CBT

into Practice and Provide Referrals to Effective

Therapists?

When discussing psychiatric disorders with patients,

family physicians are well suited to help patients decide

which services to seek. In addition to asking about

patients’ personal and family histories of psychiatric

disorders, family physicians can help patients identify

thoughts and behaviors that are contributing to their

problems. For example, avoidance behaviors (e.g., avoid-

ing crowded stores, avoiding interacting with the oppo-

site sex) help maintain anxiety disorders and PTSD.

Family physicians can encourage patients to face safe

stimuli and, if possible, seek safe fear-eliciting stimuli.

For patients with depressive symptoms, encouraging

engagement in a daily pleasant activity is helpful.

32

Family physicians are on the front line when it comes to

treatments for psychiatric disorders and can be influential

when recommending treatments to their patients. Build-

ing a collaborative relationship with community-based

behavior therapists enables family physicians to provide

comprehensive care. Table 1 provides resources for CBT,

including websites for locating therapists and informa-

tion to help patients select a therapist. For patients who

are already engaged in therapy, family physicians can

help determine whether they would benefit from CBT,

especially if the alternative is a potentially longer-term,

less cost-effective form of psychotherapy. Table 2 lists key

features of CBT that physicians can incorporate into dis-

cussions to optimize their patients’ care.

Table 1. Cognitive Behavior Therapy Resources

for Family Physicians

Academy of Cognitive Therapy – Therapist locator

http://www.academyofct.org

American Psychological Association – Therapist locator

http://locator.apa.org/

Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies

http://www.abct.org/Information/?m=mInformation&

fa=FactSheets, http://www.abct.org/information/?m=

mInformation&fa=fs_GUIDELINES_CHOOSING, and

http://www.abctcentral.org/xFAT/

Psychology Today – Therapist locator

https://therapists.psychologytoday.com/rms/prof_search.php

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

November 1, 2015

◆

Volume 92, Number 9 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 811

Data Sources: A PsycINFO search was completed using the key terms

cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, and behavior therapy.

The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical

trials, and reviews. Search dates: October and November 2014. In addi-

tion, we used an evidence summary from Essential Evidence Plus.

The Authors

SCOTT F. COFFEY, PhD, is the director of the Division of Psychology and

vice chair for research in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behav-

ior at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson.

ANNE N. BANDUCCI, PhD, is a postdoctoral research fellow at the National

Center for PTSD at the VA Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System. At the time

the article was written, she was a resident in the Department of Psychiatry

and Human Behavior at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

CHRISTINE VINCI, PhD, is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Depart-

ment of Health Disparities Research at the University of Texas M.D. Ander-

son Cancer Center, Houston.

Address correspondence to Scott F. Coffey, PhD, University of Mis-

sissippi Medical Center, 2500 N. State St., Jackson, MS 39216 (e-mail:

scoffey@umc.edu). Reprints are not available from the authors.

REFERENCES

1. Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety

disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):621-632.

2. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole S, Huibers M, Berking M, Andersson G.

Psychological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis.

Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(2):130-140.

3. Reynolds S, Wilson C, Austin J, Hooper L. Effects of psychotherapy for

anxiety in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol

Rev. 2012;32(4):251-262.

4. Sánchez-Meca J, Rosa-Alcázar AI, Marín-Martínez F, Gómez-Conesa A.

Psychological treatment of panic disorder with or without agorapho-

bia: a meta-analysis [published correction appears in Clin Psychol Rev.

2010;30 (6):815-817]. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30 (1):37-50.

5. Dobson KS, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, et al. Randomized trial of behav-

ioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the

prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depression. J Consult Clin

Psychol. 2008;76(3):468-477.

6. Mazzucchelli T, Kane R, Rees C. Behavioral activation treatments for

depression in adults: a meta-analysis and review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract.

2009;16(4):383- 411.

7. Klein JB, Jacobs RH, Reinecke MA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for

adolescent depression: a meta-analytic investigation of changes in

effect-size estimates. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 20 07;4 6 (11) :

1403-1413.

8. Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, Gillihan SJ, Foa EB. A meta-

analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder.

Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30 (6):635- 641.

9. Le QA, Doctor JN, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. Cost-effectiveness of pro-

longed exposure therapy versus pharmacotherapy and treatment

choice in posttraumatic stress disorder (the Optimizing PTSD Treat-

ment Trial): a doubly randomized preference trial. J Clin Psychiatry.

2014;75(3):222-230.

10. Daley D, van der Oord S, Ferrin M, et al.; European ADHD Guidelines

Group. Behavioral interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity dis-

order: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials across multiple

outcome domains. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(8):835-

847, 847.e1-847.e5.

11. Evans SW, Owens JS, Bunford N. Evidence-based psychosocial treat-

ments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43(4):527-551.

12. Eldevik S, Hastings RP, Hughes JC, Jahr E, Eikeseth S, Cross S. Meta-

analysis of early intensive behavioral intervention for children with

autism. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38(3):439-450.

13. Rogers SJ, Vismara LA. Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for

early autism. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37(1):8-38.

14. Rosa-Alcázar AI, Sánchez-Meca J, Gómez-Conesa A, Marín-Martínez F.

Psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-

analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(8):1310 -1325.

15. Lynch TR, Trost WT, Salsman N, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior ther-

apy for borderline personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;

3:181-205.

16. Matusiewicz AK, Hopwood CJ, Banducci AN, Lejuez CW. The effective-

ness of cognitive behavioral therapy for personality disorders. Psychiatr

Clin North Am. 2010;33(3):657-685.

17. Keel PK, Haedt A. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for eating

problems and eating disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;

37(1):39-61.

18. Okajima I, Komada Y, Inoue Y. A meta-analysis on the treatment effec-

tiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Sleep Biol

Rhythms. 2011;9 (1):24-34.

19. American Psychological Association, Society of Clinical Psychol-

ogy. Psychological treatments. http://www.div12.org/psychological-

treatments/treatments. Accessed June 2, 2015.

20. Clark DM, Ehlers A, McManus F, et al. Cognitive therapy versus fluox-

etine in generalized social phobia: a randomized placebo-controlled

trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(6):1058-1067.

21. Heuzenroeder L, Donnelly M, Haby MM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of psy-

chological and pharmacological interventions for generalized anxiety

disorder and panic disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(8):602-612.

22. Miklowitz DJ, Scott J. Psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder: cost-

effectiveness, mediating mechanisms, and future directions. Bipolar

Disord. 2009;11(suppl 2):110 -122.

23. Turner DT, van der Gaag M, Karyotaki E, Cuijpers P. Psychological inter-

ventions for psychosis: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies.

Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(5):523-538.

24. Shaw B, Segal Z. Efficacy, indications, and mechanisms of action of

cognitive therapy of depression. In: Janowsky DS. Psychotherapy Indi-

cations and Outcomes. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press;

1999:173-195.

25. Storchheim LF, O’Mahony JF. Compulsive behaviours and levels of belief

in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case-series analysis of their inter-

relationships. Clin Psychol Psychother. 20 06;13 (1) : 64-79.

26. Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, Andersson G. Adding psychotherapy to

Table 2. Core Components and Characteristics

of Cognitive Behavior Therapy

One 60- to 90-minute session per week, typically for eight

to 12 weeks

Symptom measures are collected frequently

Treatment is goal-oriented and collaborative; patient is

expected to be an active participant

Treatment is focused on changing current problematic or

maladaptive thoughts or behaviors

Weekly homework assignments

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

812 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 92, Number 9

◆

November 1, 2015

pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a

meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1219-1229.

27. Haby MM, Tonge B, Littlefield L, Carter R, Vos T. Cost-effectiveness

of cognitive behavioural therapy and selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors for major depression in children and adolescents. Aust N Z J

Psychiatry. 2004;38(8):579-591.

28. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Evans MD, et al. Cognitive therapy and phar-

macotherapy for depression. Singly and in combination. Arch Gen

Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):774-781.

29. Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Pauly MC, Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Stein MB,

Roy-Byrne P. Relative effects of CBT and pharmacotherapy in depression

versus anxiety: is medication somewhat better for depression, and CBT

somewhat better for anxiety? Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(7):560-567.

30. Beck JS. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. 2nd ed. New

York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

31. Serfaty MA, Haworth D, Blanchard M, Buszewicz M, Murad S, King M.

Clinical effectiveness of individual cognitive behavioral therapy for

depressed older people in primary care: a randomized controlled trial.

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66 (12):1332-1340.

32. Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, Jarrett RB. Reducing relapse and recur-

rence in unipolar depression: a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-

behavioral therapy’s effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(3):475-488.

33. Otto MW, Pollack MH, Sabatino SA. Maintenance of remission fol-

lowing cognitive behavior therapy for panic disorder: possible delete-

rious effects of concurrent medication treatment. Behav Ther. 1996;

27(3):473-482.

34. Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behav-

ioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the

acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol.

2006;74(4):658-670.

35. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, Stevens

SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related post-

traumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74 (5):898-907.

36. de Arellano MA, Lyman DR, Jobe-Shields L, et al. Trauma-focused

cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: assessing

the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65 (5):591-602.

37. Foa EB, McLean CP, Capaldi S, Rosenfield D. Prolonged exposure vs sup-

portive counseling for sexual abuse-related PTSD in adolescent girls: a

randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(24):2650-2657.

38. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Combined psychotherapy and pharma-

cotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: review and analysis.

Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 20 05;12(1) :72-86.

39. Pilling S, Mayo-Wilson E, Mavranezouli I, Kew K, Taylor C, Clark DM;

Guideline Development Group. Recognition, assessment and treat-

ment of social anxiety disorder: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2013;

346:f2541.

40. Bernardy NC. The role of benzodiazepines in the treatment of posttrau-

matic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD Res Q. 2013;23(4):1-9. http://www.

quantumunitsed.com/get-material.php?id=316. Accessed June 1, 2015.

41. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of condi-

tions specifically related to stress. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/

10665/85119/1/9789241505406_eng.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2015.