University of Richmond

UR Scholarship Repository

05"'-*-&5 "2*152!*(" 1(-,0 05"'-*-&5

Cognitive-Behavioral &erapy for ADHD in

College: Recommendations “Hot O% the Press”

Laura E. Knouse

University of Richmond*),-20$/("'+-,#$#2

-**-41'(0 ,# ##(1(-, *4-/)0 1 ';.0"'-* /0'(./("'+-,#$#2.05"'-*-&5% "2*15

.2!*(" 1(-,0

/1-%1'$ -2,0$*(,&05"'-*-&5-++-,0 ,#1'$ "'--*05"'-*-&5-++-,0

:(0/1("*$(0!/-2&'11-5-2%-/%/$$ ,#-.$, ""$00!51'$05"'-*-&5 1"'-* /0'(.$.-0(1-/51' 0!$$, ""$.1$#%-/(,"*20(-,(,

05"'-*-&5 "2*152!*(" 1(-,0!5 , 21'-/(6$# #+(,(01/ 1-/-%"'-* /0'(.$.-0(1-/5-/+-/$(,%-/+ 1(-,.*$ 0$"-,1 "1

0"'-* /0'(./$.-0(1-/5/("'+-,#$#2

$"-++$,#$#(1 1(-,

,-20$ 2/ -&,(1(3$$' 3(-/ *:$/ .5%-/(,-**$&$$"-++$,# 1(-,07-191'$/$008 e ADHD Report

,-2&201#-( #'#

8 • The ADHD Report © 2015 The Guilford Press

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for

ADHD in College: Recommendations

“Hot Off the Press”

Laura E. Knouse, Ph.D.

ADHD leads to impairment across the

lifespan including during the college

years. An increasing number of studies

document the academic, social, and psy-

chological impairments associated with

the disorder in college (DuPaul, Wey-

andt, O’Dell, & Varejao, 2009). Yet, until

very recently, there were no published

studies on cognitive-behavioral treat-

ment approaches specifically tailored

to college students with ADHD. Over

the past year, however, four research

groups have published work on skills-

based cognitive-behavioral treatments

for this population. My goal in this ar-

ticle is to briefly summarize these find-

ings and to identify key recommenda-

tions for clinicians working with college

students with the disorder that emerge

across studies. In addition, I will inte-

grate findings from basic research on

ADHD and memory strategies that my

colleagues and I have recently complet-

ed and make the case for inclusion of

these strategies into skills-based ADHD

treatments for college students.

It is now fairly well established that

skills-based, cognitive-behavioral treat-

ment (CBT) approaches can be effica-

cious for adults with ADHD (Knouse

& Safren, 2014). Depending on one’s

interpretation of the American Psycho-

logical Association Division 12’s criteria

for empirically supported treatments,

based in particular upon the studies

conducted by Safren and colleagues

(2010) and Solanto and colleagues

(2010), CBT for adult ADHD meets cri-

teria as at least a “probably efficacious

treatment.” Across studies, teaching

adults with ADHD to consistently use

specific compensatory behavioral skills

(e.g., organization and planning) and to

recognize and cope with the thinking

patterns that block the use of those skills

has been shown to reduce the impact of

symptoms. Likewise, specific training

in the use of organization and planning

© 2015 The Guilford Press The ADHD Report • 9

skills has been shown to help the func-

tioning of both children (Abikoff et al.,

2013) and adolescents (Langberg, Ep-

stein, Becker, Girio-Herrera, & Vaughn,

2012) with ADHD in the academic set-

ting. Yet only recently have studies

of specific applications with college

students been published, although the

subject has been covered in the clini-

cal practice literature (e.g., Ramsay &

Rostain, 2006). Importantly, these re-

cent studies are adaptations of existing

skills-based CBT approaches for adults

more generally. There are good reasons

to predict that modifications to general

adult protocols for ADHD treatment

would be necessary to achieve optimal

results, including the unique develop-

mental context of emerging adulthood

(see Fleming & McMahon, 2012, for a

review) and the heavy cognitive and

organizational load that students must

carry. Each of these research groups has

taken an independent course in adapt-

ing existing interventions, and thus

examining these studies for points of

convergence can provide useful infor-

mation for clinicians working with this

population.

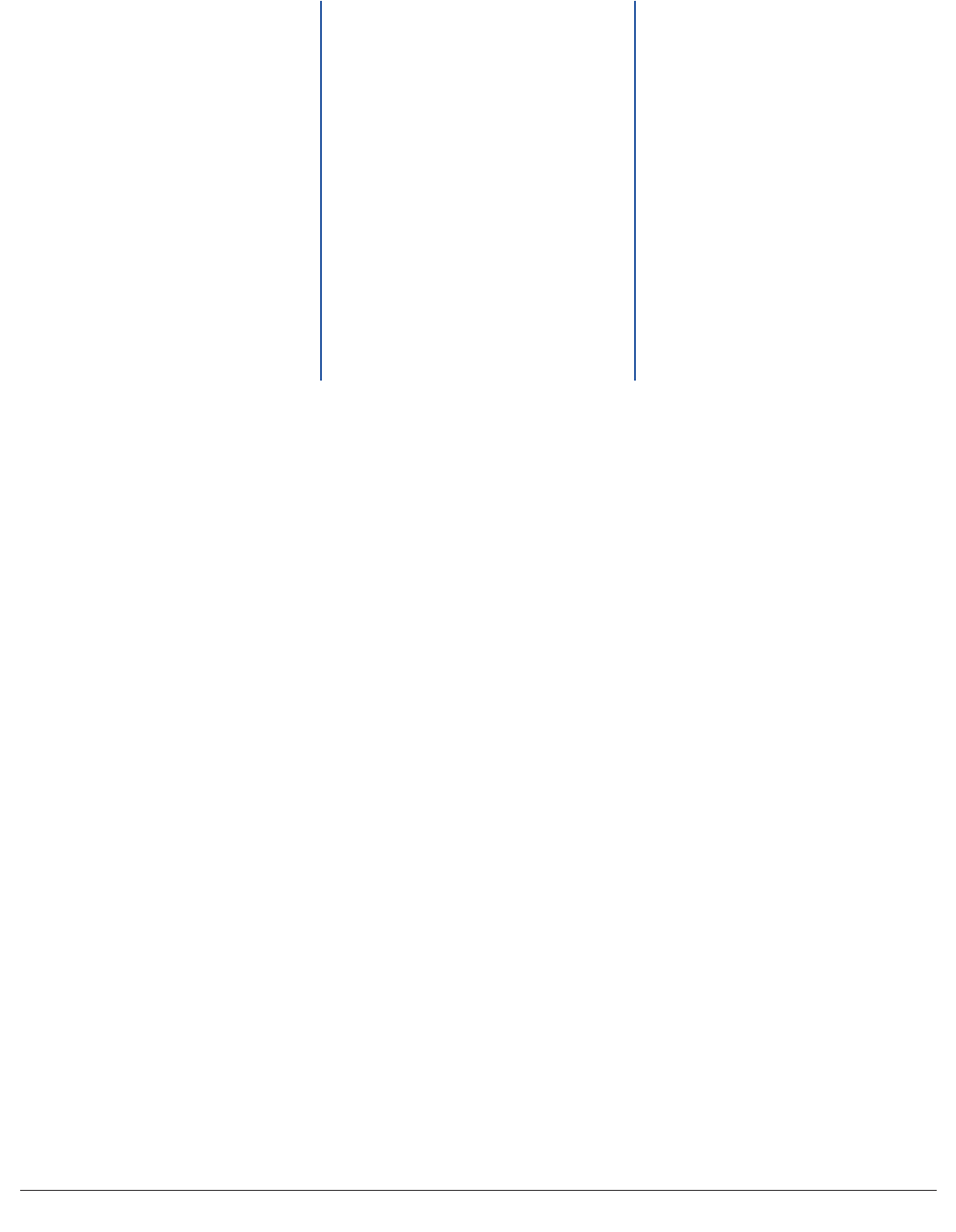

Summary details of four recent stud-

ies are presented in Table 1. The studies

represent a variety of choices in terms of

research design and clinical approach.

Readers are invited to examine Table 1

to get a general sense of the approaches

and findings from each study and may

access each manuscript if they would

like more details. Taken together, these

studies demonstrate that tailored CBT

approaches for college students with

ADHD can have a positive impact on

inattentive symptoms in particular and

on academic functioning and use of

skills.

Some clinical take-homes from these

studies include:

•Fit the treatment to the contours of

the semester

•Measure skill use and functioning,

not just symptoms

•Consider the power of the group

•Provide more frequent cues and

support

•Choose skills suited to the profes-

sional learner

FIT THE TREATMENT TO THE

CONTOURS OF THE SEMESTER

The first theme emerging across these

studies is the importance of timing the

CBT intervention so that it fits within

the constraints of the academic se-

mester. Interestingly, the four research

groups appear to independently have

determined that an intervention 8–10

weeks in length (mean of 8.5 weeks, to

be precise) starting a few weeks into

the semester is ideal for this purpose.

Several researchers emphasize the im-

portance of starting early enough in

the semester to get some skills in place

before the high-stress periods of mid-

terms and final exams while still allow-

ing sufficient time for recruitment and

pre-screening at the start of the semes-

ter. In their chapter on CBT for college

students, for example, Ramsay and Ros-

tain (2006) suggest using the finals pe-

riod as a sort of final exam for the skills

learned in CBT across the semester;

Fleming, McMahon, Moran, Peterson,

and Dreessen (2014) similarly coached

their clients to prepare for the “high de-

mand period” at the end of the semester

using previously practiced strategies.

However, clinicians in college coun-

seling centers have little control over

when clients with ADHD seek ser-

vices, and students often wait until the

situation is exceedingly dire—often, at

the end of the semester—before seek-

ing help. However, if a clinic offered a

structured CBT program for students

with ADHD each semester, as described

above, then students who present to

the clinic “in crisis” right before finals

could be strongly encouraged to enroll

in the more structured program the fol-

lowing semester.

MEASURE SkIll USE AND

FUNCTIONING, NOT JUST

SYMPTOMS

Measuring treatment outcomes as often

as weekly is an important element of

CBT approaches even when they are not

part of a formal research study. Many

CBT clinicians employ short, symptom-

based rating scales for this purpose. Re-

sults from recent studies suggest that

clinicians (and researchers!) should

consider expanding their assessments

to include skill use and functioning. To

address skill use first, at the heart of CBT

for adult ADHD lies the idea that—with

practice and support—clients can learn

behavioral skills and cognitive strate-

gies to work around their ADHD symp-

toms even when those symptoms per-

sist into adulthood (Knouse, 2015). All

of the treatment approaches reviewed

here aim to help clients learn specific

skills that will accomplish this goal, and,

consistent with the mechanism of action

for CBT, several researchers specifically

measure the extent to which clients are

using behavioral and cognitive skills.

For example, Anastopoulos and King

(2015) measured and demonstrated

pre-to-post changes in ADHD knowl-

edge, behavioral skill use, and changes

in maladaptive cognitions, as each of

these were hypothesized mechanisms of

change in their intervention. Clinically,

having clients complete formalized as-

sessments of skill use during treatment

could serve a self-monitoring function

and may increase clients’ self-efficacy

as they see evidence that their behaviors

are changing even though their symp-

toms may still present challenges.

The recent studies also indicate that

measuring improvements in function-

ing in addition to symptoms may be

both important and useful. First, func-

tional outcomes may be more in line

with clients’ goals for themselves. Eddy,

Will, Broman-Fulks, and Michael (2015)

noted that 3 of the 4 clients in their case

series prioritized the functional goals of

being able to get work done efficiently

rather than goals framed in terms of

symptom reduction. They also found

that some clients reported significant

improvements in functioning after

treatment even when there was little

movement on symptom-based ratings

scales. Thus, assessments of function-

ing may not only be more meaningful

to the client but may be more sensitive

to treatment-related change.

Busy college counseling centers re-

quire assessment tools that are time-

efficient, and therefore rating scales

tend to be preferred. To assess function-

ing, both LaCount, Hartung, Shelton,

Clapp, and Clapp (2015) and Eddy and

colleagues (2015) used the Weiss Func-

tional Impairment Rating Scale (Weiss,

2000), which may be a helpful tool to

10 • The ADHD Report © 2015 The Guilford Press

TABLE 1. Recent Studies on CBT for College Students with ADHD

Study Treatment Approach Research Design & Participants Findings Notes

Anastopoulos & King

(2015)

8 weekly group CBT sessions and individual

mentoring sessions

Open trial across 3 semesters Significant increases in ADHD knowledge (d =

2.23); Behavioral strategies (d = 1.04); and

on one of two measures of adaptive thinking

(d = .97)

“ACCESS is best viewed as an integral com-

ponent of an overall multimodal treatment

approach that includes other interventions

(e.g., medication management, counseling,

tutoring).”

Content adapted from Safren et al. (2005) and

Solanto et al. (2011)

43 enrolled; post-treatment data for 40 Significant decreases in self-reported inatten-

tive symptoms

Booster sessions offered the following semester 86% attended 80%+ group sessions; 84%

for mentoring portion

Percent using disability services increased from

19% to 57%

Each group session included ADHD knowledge,

behavioral skills, and cognitive therapy

Focus on increasing client use of campus sup-

port services

Mentoring focused on skills application, goal-

setting, and monitoring

Eddy, Canu, Broman-

Fulks, & Michael (2015)

8 weekly individual CBT sessions adapted from

Safren et al. (2005)

Case series of 4 participants assessed at

Sessions 1 and 8

Treatment attendance and satisfaction were

high for all participants

3 of the 4 participants articulated their top treat-

ment goal as working more efficiently rather

than reducing ADHD symptoms, per se

One support telephone call per week to target

skill application and to provide a reminder for

the next session

In general, measures of functional impairment

showed greater change from pre-to-post than

measures of ADHD symptoms

Client workbook

LaCount, Hartung,

Shelton, Clapp, &

Clapp (2015)

10 weekly individual and group sessions adapted

from Safren et al. (2005)

Open trial of 17 undergraduate and

graduate students; 12 (70%) completed

post-intervention measures

For completers, significant decreases in self-

reported inattentive symptoms (d = .93)

Future directions include examining effects of

treatment components (individual vs. group;

specific skills); see text for description of

recent study along these lines

Group components provided social support and

greater exposure to material

Completers attended 85% of individual

sessions and 77% of group sessions

Significant reductions in impairment at school (d

= .51) and at work (d = .63)

Individual sessions focused on each client’s indi-

vidual goals and skills practice (homework)

Fleming, McMahon,

Moran, Peterson, &

Dreessen (2015)

8 weekly group sessions with 10–15-minute

coaching telephone calls

Randomized controlled trial comparing 17

participants receiving intervention to 16

participants receiving handouts covering

ADHD self-management skills

Both groups significantly improved in their DSM-

IV inattentive symptoms post-treatment; trend

toward greater improvement in the treatment

group (d = .55)

Clinical response rate to the handout control con-

dition (25%) was comparable to rates achieved

with active treatment controls (e.g., supportive

group therapy) suggesting its potential as a

low-cost intervention

1 booster session at the start of the following

quarter

Participants in the treatment group attend-

ed 88% of sessions with one drop-out

At 3-month follow-up, treatment group had sig-

nificantly lower inattentive symptoms (d = .81)

Based on dialectical behavior therapy: empha-

sized mindfulness skills but more heavily

integrated organization and planning skills

than typical DBT

Treatment group showed significantly greater

improvements in quality of life at post-treat-

ment (d = .90) and gave high helpfulness

ratings to most treatment components

Designed to fit developmental context of emerg-

ing adults (e.g., peer support)

© 2015 The Guilford Press The ADHD Report • 11

use in clinical practice. With respect to

skills, well-established commercially

available measures like the Learning

and Study Strategies Inventory (LAS-

SI; Weinstein & Palmer, 2002) could be

useful for showing treatment-related

change but may be too burdensome for

frequent use. To measure utilization of

skills like calendar use and goal setting,

Anastopoulos and King (2015) devel-

oped the 30-item Strategies for Success

scale. Likewise, Solanto and colleagues

(2010) developed the 24-item On Time

Management, Organization, and Plan-

ning Scale (ON-TOP) to measure use

of skills in their trial of group CBT for

adults. Clinicians could seek out these

or similar scales to use with clients in

CBT or could choose a customized list

of items tapping the skills that each cli-

ent will target in therapy. Regardless of

the method, tracking progress in treat-

ment using multiple methods gives

both clinician and client more informa-

tion to use in shaping the treatment as it

evolves and in highlighting the results

of the client’s efforts, providing rein-

forcement for behavior change.

CONSIDER THE POwER OF

THE GROUP

Group treatments offer several ad-

vantages, some of which may be even

more salient for college students. Three

of the recent studies used a group for-

mat, either as the primary intervention

(Fleming et al., 2015) or in tandem with

individual sessions (Anastopoulos &

King, 2015; LaCount et al., 2015) to cre-

ate a multimodal treatment. Given the

importance of peer relationships dur-

ing this developmental period (Flem-

ing & McMahon, 2012), LaCount and

colleagues (2015) note that the group

context provides an opportunity to re-

duce ADHD–related stigma through

contact with students struggling with

similar issues. Further, college students

are likely to have experiences and daily

challenges more similar to one another

than to a group of adults from the gen-

eral population, increasing the opportu-

nity for empathy, social support, and es-

pecially modeling of skill use within the

group (LaCount et al., 2015). In my own

clinical experience, the group context

also helps reluctant students accept the

fact that they need to use skills and do

things differently than their peers with-

out ADHD—a struggle noted by others

working with college students (Ramsay

& Rostain, 2006; Anastopoulos & King,

2015). And as noted by Anastopoulos

and King (2015), allowing students to

interact and support one another out-

side of the group can be a way to embed

social cues for skill use in the environ-

ment more frequently throughout the

week.

(Clinicians should of course lay

out the ground rules for confidentiality

within the group and facilitate discus-

sion within the group about whether

the members would like to interact

outside the group context.) Further, the

students themselves can introduce new

skill tips and tricks to the group and

provide testimonials about their own

successes and struggles using the tech-

niques.

In addition to affording certain thera-

peutic advantages, groups are certainly

time- and cost-effective, which is an im-

portant consideration in college coun-

seling centers with limited resources.

Yet groups are not without their own

unique challenges. First, since CBT skills

groups are usually highly structured,

the therapist must have the ability to

skillfully guide members back on track

when they get off topic. Setting expecta-

tions about the structured nature of the

group up front is exceedingly important

in this regard. Second, because mem-

bers may feel less of a personal stake

in the group than they do in individual

therapy, therapists should emphasize

the importance of attendance and the

importance of each group member to

the overall success of the group thera-

peutic endeavor. Relatedly, the therapist

needs to be sensitive to the engagement

of all members in the group process and

allow time for each to discuss his or

her experiences and the results of skills

practice from the prior week.

In order to provide individualized

attention to clients while capitalizing on

the advantages of the group, LaCount

and colleagues (2015) and Anastopou-

los and King (2015) developed interven-

tions with both group and individual

components. For both research groups,

the goals of the individual component

were to focus on each client’s application

of the skills covered in group therapy

and to aid the client in setting concrete

goals and monitoring progress toward

those goals (e.g., completion of weekly

therapy homework assignments). Thus,

adding an individual component to a

group-based intervention allows for

more individualized trouble-shooting

of skill use and greater accountability

for students to follow through on skills

practice. In these studies, graduate stu-

dents served as individual therapists.

However, at schools without graduate

programs or with fewer resources, in-

dividual peer coaching (Zwart & Kalle-

myn, 2001) centering around skill appli-

cation and goal-setting combined with

therapist-led groups might be a feasible

alternative.

PROvIDE MORE FREqUENT CUES

AND SUPPORT

A week is a long and action-packed pe-

riod of time in the life of a college stu-

dent, and many students with ADHD

find it difficult to maintain their engage-

ment with newly learned skills between

sessions. All of the recently developed

treatments addressed this challenge by

providing some form of reminders or

cues for skills use between weekly ses-

sions. As mentioned above, two treat-

ments involved full individual therapy

components in addition to group ses-

sions. Eddy and colleagues (2015) pro-

vided individual therapy augmented

with one supportive telephone call per

week between sessions. The purpose of

the call was to provide guidance with

skills and homework assignments as

needed, as well as to remind the par-

ticipant of his or her next appointment.

Participants also received the Mastering

Your Adult ADHD workbook (Safren,

Sprich, Perlman, & Otto, 2005) to guide

their between-session practice. Flem-

ing and colleagues (2015) also provided

10–15 minute coaching telephone calls

that focused on helping clients apply

and generalize the skills learned in

the 90-minute group sessions to their

daily lives. Thus, each of these clinical

research groups has recognized the im-

portance of treatment components that

help clients generalize skills beyond the

weekly therapy session. (As I often say

to my clients, the therapy hour is less

than 1% of your week, and if nothing

changes outside of that hour, we have

missed the boat!)

12 • The ADHD Report © 2015 The Guilford Press

In addition to individual sessions,

peer coaching or mentoring, and coach-

ing telephone calls, there may be other

creative ways to help college students

generalize skills to their daily lives.

Technology may provide some help-

ful, low-cost routes. For example in a

CBT skills group that I ran, I sent short

emails mid-week containing self-moni-

toring questions clients could ask them-

selves regarding their use of skills so

far that week and brief coaching about

either maintaining skills or getting back

on track. Since many students carry

smartphones with them, short emails

(short = more likely to be read) or text

messages may be a useful way to pro-

vide accessible cues. Clients can also

be coached to cue themselves by us-

ing the calendar and alarm features on

their smartphones to set reminders for

skill check-ins, as suggested by Safren

and colleagues (2005). More frequent

and intense support for skill applica-

tion in daily life is often needed to help

clients generalize outside the clinic, and

even clinicians in settings with fewer

resources can find opportunities to cue

skills outside of session.

CHOOSE SkIllS SUITED TO THE

PROFESSIONAl lEARNER

In many ways, college is not like the

“real world.” Some aspects of life may

be relatively less burdensome (e.g., han-

dling daily responsibilities like cooking

and home maintenance, although many

college students also manage house-

holds, work full-time for pay, and take

care of family members. Thus treatment

must always be tailored to the needs

of each client.). Others may be more

intense and challenging (coordinating

and completing assignments requiring

disparate skill sets; learning, retaining,

and applying large amounts of differ-

ent types of information over varying

lengths of time—all while resisting nu-

merous opportunities for procrastina-

tion). Recognizing the unique challeng-

es of college for students with ADHD,

each research group made adaptations

to the content of the adult-focused in-

terventions they based their treatments

upon (see Table 1).

First, several authors highlight the

need to intensely target procrastina-

tion and avoidance patterns in college

students. Ramsay and Rostain (2006)

highlight the role of procrastination

and avoidance as responses to task-re-

lated anxiety and maladaptive thoughts

that compound functional impairment

in the long-term. In their case series,

Eddy and colleagues (2015) recom-

mend moving content and skills related

to procrastination to the very begin-

ning of treatment and highlighted the

role of cognitive reappraisal skills in

reducing anxiety and cueing active skill

use instead of avoidance—a point also

emphasized by Anastopoulos & King

(2015). The mindfulness skills taught

by Fleming and colleagues (2015) in

their DBT approach can also be used in

the service of reducing the automatic,

reactive avoidance triggered by nega-

tive thoughts and emotions (Knouse &

Mitchell, 2015).

Second, every study described here

placed heavy emphasis on organiza-

tion, time-management, and planning

skills to help college students manage

and balance the diverse tasks that de-

mand their attention. These skills are

at the heart of CBT for adults in general

(Safren, Perlman et al., 2005; Solanto,

2011) and should also be a core compo-

nent of work with college students. In

fact, in an interesting next-step study

recently presented at the annual con-

ference for the Association for Behav-

ioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT),

LaCount, Hartung, and Shelton (2014)

reported results from a trial of a very

brief (3-session) group-based interven-

tion adapted from Solanto (2011) and

focusing only on organization and

time management skills (scheduling,

breaking down tasks and self-reward,

prioritizing and task lists). Recruiting

undergraduates with elevated scores

for ADHD symptoms and impairment,

LaCount and colleagues (2014) found

that relative to a comparison group (n

= 16), the group receiving the brief in-

tervention (n = 25) showed a significant

reduction in Inattentive symptoms of

ADHD. Means were also in the hypoth-

esized direction on a measure of organi-

zation, time-management, and planning

skills, although the differences did not

reach significance. The study demon-

strated that even a brief intervention

targeting critical areas of impairment for

people with ADHD may be helpful and

further supports the importance of orga-

nization, time-management, and plan-

ning skills in helping college students

with ADHD function more effectively.

Finally, I would like to suggest that

researchers and clinicians working with

college students with ADHD consider

incorporating specific empirically sup-

ported study skills and strategies into

their CBT work. Only one of the treat-

ment approaches reviewed here, that of

Anastopoulos and King (2015), appears

to have incorporated specific study

skills and strategies: one session each

containing information on getting the

most from classes, studying effectively,

and strategies for taking exams. To con-

clude this article, I would like to present

the case for more frequent incorpora-

tion of study strategies into CBT for col-

lege students with ADHD—specifically,

the strategy of retrieval practice, or test-

enhanced learning.

As professional learners, college stu-

dents are tasked with encoding, retain-

ing, and retrieving larger amounts of

more diverse information than perhaps

at any other point in their adult lives.

For much of this learning, it is incum-

bent upon the student to choose the tim-

ing and frequency of study as well as

the learning techniques to be employed.

Critically, in basic research on memory,

adults with ADHD tend to show the

most substantial memory deficits when

tasks require such self-regulated, effort-

ful memory encoding (Holdnack, Mo-

berg, Arnold, Gur, & Gur, 1995; Roth et

al., 2004; Seidman, Biederman, Weber,

Hatch, & Faraone, 1998). For example,

my colleagues and I (Knouse, Anasto-

poulos, & Dunlosky, 2012) conducted a

study in which we gave adults with and

without ADHD an unstructured, open-

ended learning task: learn 40 noun-noun

word pairs (e.g., garden-sister) printed

on one side of a set of cards for a later

test in which the participant was given

the first word and had to recall its mate.

Participants were given no time limits

nor any hints as to how they should

study the words. On this task, a group

of adults with ADHD (n = 34), who did

not differ from a non-ADHD group (n =

34) in terms of estimated full scale IQ or

© 2015 The Guilford Press The ADHD Report • 13

education, recalled significantly fewer

words (M = 22.48, SD = 13.06 vs. M =

29.96, SD = 10.89; Cohen’s d = .62). In

practical terms, if this had been a grad-

ed quiz, the non-ADHD group would

have earned, on average, a solid C com-

pared to an F average in the group with

ADHD.

These results beg the question of

whether, as a group, adults with ADHD

approached the task differently—in a

way that could explain their differences

in learning. In other words, what were

they doing or not doing when asked to

study the words? To answer this ques-

tion, we measured a variety of possible

strategy approaches the participants

could have used as well as their self-re-

ported effort and the time they chose to

spend on the task. We found that partic-

ipants’ self-testing behavior—or, the ex-

tent to which they quizzed themselves

on the items while studying—best dif-

ferentiated the behavior of the groups.

Fifty-one percent of people in the

ADHD group were observed to self-test

even once compared to 82% of the non-

ADHD group. Although we were not

able to directly test whether self-testing

produced the between-group differenc-

es in memory test performance, failure

to self-test was associated with poorer

memory performance across groups

(Cohen’s d = 1.11). And although our

study did not specifically test college

students, our results dovetail with an

investigation of the self-reported study

strategies of college students with

ADHD in which they reported less

frequently using effortful but effective

strategies including self-testing (Reaser,

Prevatt, Petscher, & Proctor, 2007).

If college students with ADHD are

under-utilizing self-testing, this pres-

ents a potentially powerful target for

intervention. Retrieval practice—or tak-

ing tests on to-be-learned material, that

is, self-testing—is among the most pow-

erful learning strategies and produces

some of the most robust memory effects

in the cognitive psychology literature

(Roediger & Butler, 2011). Many stu-

dents use it as an assessment strategy to

figure out what information they have

and have not yet retained. But retriev-

ing items from memory also has a direct

impact on the likelihood of remember-

ing those items. In a recent monograph,

Dunlosky, Rawson, Marsh, Nathan, and

Willingham (2013) reviewed the empiri-

cal evidence for ten commonly used

learning strategies and found the most

support for the effectiveness of practice

testing and distributed practice (study-

ing in sessions spaced across time).

Yet college students—including those

without ADHD—under-utilize prac-

tice testing, preferring less effective and

less effortful strategies like highlight-

ing or re-reading (Karpicke, Butler, &

Roediger, 2009). If college students with

ADHD are even less likely to use self-

testing than their non-ADHD peers, as

seems likely from past studies, train-

ing in this straightforward yet effective

strategy might have the potential to

make a large therapeutic impact.

But despite the robustness of the test-

ing effect, shockingly little research has

examined the magnitude of the effect in

clinical populations, and no prior study

has examined the magnitude of the

testing effect in ADHD. In other words,

we know that the strategy works for

people without ADHD, but we do not

have direct evidence that it works for

people with ADHD. Thus, in order to

know whether this skill should be used

as part of an intervention, we need to

know whether it is actually effective for

students with ADHD when they do use

it. This was the motivation for a study

we recently completed on the testing ef-

fect in college students with ADHD.

My colleagues and I (Knouse, Raw-

son, Vaughn, & Dunlosky, 2015) inves-

tigated whether college students with

ADHD show the testing effect—that is,

do they show significant gains in long-

term recall when given the opportu-

nity to practice retrieval above and be-

yond their performance when simply

restudying items? We also compared

whether any memory benefits of testing

were comparable in magnitude for stu-

dents with and without ADHD. To test

our hypotheses, we recruited 25 college

students diagnosed with ADHD who

met several inclusion criteria and com-

pared them to 75 students with no histo-

ry of ADHD but matched to the ADHD

group on their basic recall performance.

Participants completed a computerized

memory task in which they studied two

separate lists of 40 words each.*

For List

A, they simply saw the list in a random-

ized order 8 times, restudying each time

(study trials). For List B, participants

had a study trial followed by the chance

to recall and type in as many words as

they could (test trial): this process was

repeated four times, resulting in four

study trials and four test trials for List B,

compared to the eight study-only trials

for List A. Participants then returned to

the lab two days later and were asked to

recall as many words as possible from

each list. The advantage in number of

words recalled for the study-test list vs.

the study-only list represents the testing

effect.

We found evidence for a moder-

ate testing effect in both students with

and without ADHD. Specifically, both

groups remembered more words from

the list that they had taken tests on

while studying compared to the list that

they had only studied (main effect of

encoding condition, F(1, 98) = 21.42, p <

.001 , η

p

2

= .179). Further, the magnitude

of this effect was comparable for both

groups as evidenced by no interaction

of condition by group and a similar ef-

fect of test-only vs. study-test in each

group (ADHD: d = .57; non-ADHD: d

= .50). The take-home message is that,

admittedly under ideal conditions, stu-

dents with ADHD showed just as much

memory advantage when using self-

testing during studying as did students

without ADHD.

In sum, our study showed that re-

trieval practice has the potential to help

college students with ADHD study

more efficiently and effectively. Ad-

ditional studies are needed to extend

the findings to more representative

learning situations and materials. In

addition, knowing that the strategy can

work for students with ADHD is only a

first step because getting clients to actu-

ally use effective strategies is often the

bigger hurdle. We plan to conduct addi-

tional studies investigating how best to

*Words in the lists could also be grouped into categories, which enabled us to test one hypothesis about the mechanisms of the testing effect that is less germane to the

current discussion. For more information, see Knouse et al., 2015.

14 • The ADHD Report © 2015 The Guilford Press

cue and support the use of this strategy

for students in real world contexts.

In the meantime, however, there is

ample evidence for the efficacy of prac-

tice testing as a general study strategy to

support recommending it to college stu-

dents with ADHD wishing to improve

the efficiency of their studying. In this

regard, clinicians in college counseling

centers could look for opportunities

to partner with staff at academic skills

centers on campus because that staff

often has specific expertise in learning

and study strategies. Clinicians can also

work with their clients to identify use-

ful online or smartphone apps that sup-

port self-testing while studying (e.g.,

Quizlet.com, Chegg flashcards). Paper

flashcards are another tried-and-true

tool. I advise my students to try to think

like a professor and create questions

they think I would put on an exam to

use when studying. Students can also

collaborate to share flashcards, create

practice tests for one another, and quiz

each other during group study sessions.

As with any new skill, the most power-

ful teacher will be the student’s own ex-

perience of success after putting in the

effort to use the method. In that regard,

clinicians could even use an in-session

demonstration of the testing effect to

help increase client motivation to use

the strategy.

CONClUSION

In sum, CBT for adults with ADHD is

undergoing an exciting evolution as a

result of clinical researchers’ efforts to

adapt the interventions for college stu-

dents. They have thoughtfully consid-

ered the setting and the specific needs of

this group of adults with ADHD when

tailoring their interventions. Likewise,

each clinician working with college stu-

dents must tailor CBT to each client and

consider his or her specialized needs

as a professional learner. Hopefully,

the recommendations offered here will

prove useful in this endeavor.

Dr. Knouse is an assistant professor in the

Department of Psychology at the Universi-

ty of Richmond and a member of the ADHD

Report Advisory Board. She can be con-

tacted at Department of Psychology, Uni-

versity of Richmond, Richmond Hall, 28

Westhampton Way, Richmond, VA 23173.

E-mail: [email protected].

REFERENCES

Abikoff, H., Gallagher, R., Wells, K. C.,

Murray, D. W., Huang, L., Lu, F., & Petkova,

E. (2013). Remediating organizational func-

tioning in children with ADHD: Immediate

and long-term effects from a random-

ized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 81(1), 113-128.

doi:10.1037/a0029648

Anastopoulos, A. D., & King, K. A. (2015). A

cognitive-behavior therapy and mentoring

program for college students with ADHD.

Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22, 141-151.

doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.002

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J.,

Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013).

Improving students’ learning with effective

learning techniques: Promising directions

from cognitive and educational psychology.

Psychological Science in the Public Interest,

14(1), 4-58. doi:10.1177/1529100612453266

DuPaul, G. J., Weyandt, L. L., O’Dell, S. M.,

& Varejao, M. (2009). College students with

ADHD: Current status and future direc-

tions. Journal of Attention Disorders, 13(3),

234-250. doi:10.1177/1087054709340650

Eddy, L. D., Canu, W. H., Broman-Fulks, J.

J., & Michael, K. D. (2015). Brief cognitive

behavioral therapy for college students

with ADHD: A case series report. Cogni-

tive and Behavioral Practice, 22, 127-140.

doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.05.005

Fleming, A. P., & McMahon, R. J. (2012).

Developmental context and treatment prin-

ciples for ADHD among college students.

Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review,

15(4), 303-329. doi:10.1007/s10567-012-

0121-z

Fleming, A. P., McMahon, R. J., Moran, L.

R., Peterson, A. P., & Dreessen, A. (2015). Pi-

lot randomized controlled trial of dialectical

behavior therapy group skills training for

ADHD among college students. Journal of

Attention Disorders. Advance online publica-

tion. doi:10.1177/1087054714535951

Holdnack, J. A., Moberg, P. J., Arnold, S.

E., Gur, R. C., & Gur, R. E. (1995). Speed

of processing and verbal learning deficits

in adults diagnosed with attention deficit

disorder. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology,

and Behavioral Neurology, 8, 282-292.

Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roedi-

ger, H. L. (2009). Metacognitive strate-

gies in student learning: Do students

practice retrieval when they study on

their own? Memory, 17(4), 471-479.

doi:10.1080/09658210802647009

Knouse, L. E. (2015). Treatment of adults

with ADHD: Cognitive-behvioral therapies

for ADHD. In R. A. Barkley (Ed.), Attention-

deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for

diagnosis and treatment (4th ed., pp. 757-773).

New York: Guilford.

Knouse, L. E., Anastopoulos, A. D., & Dun-

losky, J. (2012). Isolating metamemory defi-

cits in the self-regulated learning of adults

with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders,

16, 650-660. doi:10.1177/1087054711417231

Knouse, L. E., & Mitchell, J. T. (2015).

Incautiously optimistic: Positively valenced

cognitive avoidance in adult ADHD. Cogni-

tive and Behavioral Practice, 22, 192-202.

doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.06.003

Knouse, L. E., Rawson, K. A., Vaughn, K. E.,

& Dunlosky, J. (2015). Does testing improve

learning for college students with attention-

deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Clinical

Psychological Science. Advance online publi-

cation. doi:10.1177/2167702614565175

Knouse, L. E., & Safren, S. A. (2014). At-

tention/deficit-hyperactivity disorder in

adults. In S. G. Hofmann (Ed.), The Wiley

handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy (pp.

713-737). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

LaCount, P. A., Hartung, C. M., & Shelton,

C. R. (2014). Efficacy of an organizational

intervention for college students with attention-

related acacemic difficiulties. Paper presented

at the annual convention of the Association

for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies,

Philadelphia, PA.

LaCount, P. A., Hartung, C. M., Shelton, C.

R., Clapp, J. D., & Clapp, T. K. W. (2015).

Preliminary evaluation of a combined

group and individual treatment for college

students with attention-deficit/hyperactivi-

ty disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice,

22, 152-160. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.07.004

Langberg, J. M., Epstein, J. N., Becker, S. P.,

Girio-Herrera, E., & Vaughn, A. J. (2012).

Evaluation of the homework, organization,

and planning skills (HOPS) intervention for

middle school students with attention defi-

cit hyperactivity disorder as implemented

by school mental health providers. School

Psychology Review, 41(3), 342.

Ramsay, J. R., & Rostain, A. L. (2006). Cog-

nitive behavior therapy for college students

with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disor-

der. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy,

21(1), 3-20. doi:10.1300/J035v21n01_02

Reaser, A., Prevatt, F., Petscher, Y., &

Proctor, B. (2007). The learning and study

strategies of college students with ADHD.

Psychology in the Schools, 44, 627-638.

Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The

critical role of retrieval practice in long-term

retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1),

© 2015 The Guilford Press The ADHD Report • 15

20-27. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

tics.2010.09.003

Roth, R. M., Wishart, H. A., Flashman, L.

A., Riordan, H. J., Huey, L., & Saykin, A.

J. (2004). Contribution of organizational

strategy to verbal learning and memory in

adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder. Neuropsychology, 18, 78-84.

Safren, S. A., Perlman, C. A., Sprich, S., &

Otto, M. W. (2005). Mastering your adult

ADHD: A cognitive-behavioral treatment

program, therapist guide. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Safren, S. A., Sprich, S., Mimiaga, M. J., Sur-

man, C., Knouse, L. E., Groves, M., & Otto,

M. W. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy

vs. relaxation with educational support for

medication-treated adults with ADHD and

persistent symptoms. JAMA, 304(8), 857-

880. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1192

Safren, S. A., Sprich, S., Perlman, C. A., &

Otto, M. W. (2005). Mastering your adult

ADHD: A cognitive-behavioral treatment

program client workbook New York: Oxford

University Press.

Seidman, L. J., Biederman, J., Weber, W.,

Hatch, M., & Faraone, S. V. (1998). Neu-

ropsychological function in adults with

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Biological Psychiatry, 44, 260-268.

Solanto, M. V. (2011). Cognitive-behavioral

therapy for adult ADHD: Targeting executive

dysfunction. New York: Guilford.

Solanto, M. V., Marks, D. J., Wasserstein, J.,

Mitchell, K., Abikoff, H., Alvir, J., & Kof-

man, M. D. (2010). Efficacy of metacognitive

therapy for adult ADHD. American Journal

of Psychiatry, 167, 958-968. doi:10.1176/appi.

ajp.2009.09081123

Weinstein, C. E., & Palmer, D. R. (2002).

Learning and Study Strategies Inventory

(LASSI): User’s manual (2nd ed.). Clearwa-

ter, FL: H & H Publishing.

Weiss, M. D. (2000). Weiss Functional

Impairment Rating Scale, retrieved from

http://naceonline.com/AdultADHDtool-

kit/assessmenttools/wfirs.pdf.

Zwart, L. M., & Kallemyn, L. M. (2001).

Peer-based coaching for college students

with ADHD and learning disabilities. Jour-

nal of Postsecondary Education and Disability,

15, 1-15.