A Randomized Controlled Trial Examining CBT for College Students

With ADHD

Arthur D. Anastopoulos

1

, Joshua M. Langberg

2

, Laura D. Eddy

1

, Paul J. Silvia

3

, and Jeffrey D. Labban

4

1

Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of North Carolina Greensboro

2

Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University

3

Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina Greensboro

4

Department of Health and Human Sciences, University of North Carolina Greensboro

Objective: College students with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at increased risk for

numerous educational and psychosocial difficulties. This study reports findings from a large, multisite

randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of a treatment for this population, known as

ACCESS—Accessing Campus Connections and Empowering Student Success. Method: ACCESS is a

cognitive– behavioral therapy program delivered via group treatment and individual mentoring across

two semesters. A total of 250 students (18 –30 years of age, 66% female, 6.8% Latino, 66.3% Caucasian)

with rigorously defined ADHD and comorbidity status were recruited from two public universities and

randomly assigned to receive ACCESS immediately or on a 1-year delayed basis. Treatment response

was assessed on three occasions, addressing primary (i.e., ADHD, executive functioning, depression,

anxiety) and secondary (i.e., clinical change mechanisms, service utilization) outcomes. Results: Latent

growth curve modeling (LGCM) revealed significantly greater improvements among immediate AC-

CESS participants in terms of ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, clinical change mechanisms, and

use of disability accommodations, representing medium to large effects (Cohen’s d, .39 –1.21). Across

these same outcomes, clinical significance analyses using reliable change indices (RCI; Jacobson &

Truax, 1992) revealed significantly higher percentages of ACCESS participants showing improvement.

Although treatment-induced improvements in depression and anxiety were not evident from LGCM, RCI

analyses indicated that immediate ACCESS participants were less likely to report a worsening in

depression/anxiety symptoms. Conclusions: Findings from this RCT provide strong evidence in support

of the efficacy and feasibility of ACCESS as a treatment for young adults with ADHD attending college.

What is the public health significance of this article?

College students with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) face numerous challenges in

their daily lives that make it difficult to achieve personal and career goals. Findings from our recently

completed clinical trial show that ACCESS—Accessing Campus Connections and Empowering

Student Success—is a promising new evidence-based treatment that gives college students with

ADHD the knowledge and skills necessary to be more successful.

Keywords: ADHD, college students, cognitive– behavioral therapy, intervention, clinical trial

Supplemental materials: https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000553.supp

Arthur D. Anastopoulos X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6096-0650

Laura D. Eddy X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5059-8344

Jeffrey D. Labban X https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3138-6925

Additional information about ACCESS, including information about

the treatment manual and study-specific measures, can be found at:

https://accessproject.uncg.edu/. The authors wish to disclose the fol-

lowing potential conflicts of interest. Arthur D. Anastopoulos, Joshua

M. Langberg, and Laura D. Eddy are authors on a forthcoming publi-

cation entitled, CBT for College Students with ADHD—A Clinical

Guide to ACCESS. Arthur D. Anastopoulos is also a co-author of the

ADHD Rating Scale–5, a modified version of which was used in this

study. The research reported here was supported by the Institute of

Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant

R305A150207 awarded to the University of North Carolina Greens-

boro. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not

represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

We thank the disability, student health, and counseling service staffs at

both universities for their partnership in referring college students to the

study and for providing presentations about their services to study

participants. We would also like to extend a special thank you to Kevin

R. Murphy for his invaluable contributions to the project as a member

of the expert review panel.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Arthur D.

Anastopoulos, Department of Human Development and Family Studies,

University of North Carolina Greensboro, ADHD Clinic at UNCG, 1100

West Market Street, 3rd Floor, Greensboro, NC 27402, United States.

Email: [email protected]

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

© 2021 American Psychological Association 2021, Vol. 89, No. 1, 21–33

ISSN: 0022-006X https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000553

21

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; American

Psychiatric Association, 2013) is characterized by developmen-

tally inappropriate symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity-

impulsivity that remain present and impair functioning across the

life span. Although much has been learned about the impact of

ADHD on children and adults (Barkley, 2015), relatively less

research attention has been directed to the way in which ADHD

unfolds among individuals transitioning through the developmen-

tal period known as emerging adulthood, from 18 to 25 years of

age (Arnett, 2007). Most of what is known about this segment of

the ADHD population comes from studies of young adults attend-

ing 4-year colleges, which in recent years have witnessed dramatic

increases in their enrollments of students with ADHD (Eagan et

al., 2014; Weyandt & DuPaul, 2012). For those individuals with

ADHD who achieved a level of success during high school that

made postsecondary admission possible, it would seem reasonable

to expect that they might be able to continue displaying educa-

tional success during college. Contrary to this expectation, once

enrolled in college, students with ADHD display significant aca-

demic deficits, including lower end-of-semester grade point aver-

ages (GPAs) and less effective study strategies, relative to their

non-ADHD peers (DuPaul et al., 2018; Gormley et al., 2019).

Although the directionality of the association is unclear, up to 55%

of the ADHD college student population may also display comor-

bid psychiatric disorders, most often involving active depressive

(32.3%) or anxiety (28.6%) disorders (Anastopoulos et al., 2018).

Additional impairment has been reported in terms of poorer ad-

justment to college (Blasé et al., 2009) and an overall lower quality

of life (Pinho et al., 2019). Together, such findings may help to

explain why college students with ADHD are more likely to be

placed on academic probation, to take longer to complete their

degrees, and to drop out of college (Barkley et al., 2008; DuPaul

et al., 2018; Hechtman, 2017).

Conceptually, it has been suggested that such difficulties are set

in motion by a “perfect storm” of life circumstances that converge

following the transition from high school into college (Anastopou-

los & King, 2015). Upon enrolling in college, all students face

increased demands for self-regulation, not only with respect to

educational matters but also in terms of various personal and social

responsibilities. This developmental transition is normative and

often the reason why many first-year students, whether they have

ADHD or not, experience trouble adjusting to college. For students

with ADHD, navigating this developmental transition is substan-

tially more challenging, in large part due to their lack of age-

appropriate self-regulation abilities (Barkley, 2015; Fleming &

McMahon, 2012). Further complicating matters is the fact that

many external supports that were in place prior to college, such as

parental monitoring and school-based 504 accommodations, are no

longer available (Meaux et al., 2009).

To reduce risk for negative outcomes, it is critically important

for college students with ADHD to have ready access to treatment.

On many college campuses, disability service accommodations are

the primary mechanism by which students with ADHD receive

assistance (Wolf et al., 2009). Unfortunately, many college stu-

dents choose not to use such services (Fleming & McMahon,

2012). Moreover, when used alone, disability accommodations

appear to produce minimal long-term benefits (e.g., Lewandowski

et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2015) and do not directly address

co-occurring executive functioning deficits (Antshel et al., 2014)

and psychiatric disorders (Anastopoulos et al., 2018). Stimulant

medication is another treatment option that has been well estab-

lished in children and adults (Barkley, 2015), but research address-

ing its use with college students has been limited to only one

clinical trial (DuPaul et al., 2012). Despite this study’s promising

results, showing that lisdexamfetamine dimesylate reduced ADHD

symptoms and improved executive functioning, additional medi-

cation trials are needed to evaluate efficacy in conjunction with

safety concerns, including the risk for misuse, abuse, and diversion

on college campuses (Rabiner et al., 2009).

More recently, psychosocial interventions for college students

with ADHD have been developed and pilot tested (He & Antshel,

2017). These investigations incorporate a diverse array of thera-

peutic perspectives, including cognitive– behavioral therapy (CBT;

LaCount et al., 2015; Van der Oord et al., 2020), coaching (Prevatt

& Yelland, 2015), dialectical behavior therapy (Fleming et al.,

2015), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Gu et al., 2018),

self-monitoring (Scheithauer & Kelley, 2017), and organization,

time management, and planning skills training (OTMP; LaCount et

al., 2018).

Findings from these initial investigations have consistently re-

vealed significant improvements in primary ADHD symptoms,

most often involving inattention (Fleming et al., 2015; Gu et al.,

2018; LaCount et al., 2015; LaCount et al., 2018,). Less often,

improvements in self-reported executive functioning (Fleming et

al., 2015) and symptoms of depression and anxiety (Gu et al.,

2018) have been observed. Although not routinely assessed, im-

provements in educational functioning have been reported, includ-

ing decreases in self-reported academic impairment (LaCount et

al., 2018), gains in self-reported learning strategies (LaCount et al.,

2015; Prevatt & Yelland, 2015) and increased use of disability

services and other campus resources (Anastopoulos & King,

2015). Notably, corresponding improvements in GPA have not

been reliably demonstrated (Fleming et al., 2015; Gu et al., 2018;

LaCount et al., 2018).

Taken together, results from this emerging literature offer much

promise for the role that psychosocial interventions, especially

CBT programs, may play in the overall clinical management of

college students with ADHD. At the same time, it is necessary to

acknowledge that reported findings have been inconsistent across

investigations, which limits conclusions about efficacy. Given that

programmatic research in this area has been lacking, many of these

inconsistent findings are likely attributable to methodological lim-

itations and differences across studies (He & Antshel, 2017).

These limitations include, for example, the use of small samples

(n ⬍ 60) drawn from single-site university settings. Diagnostic

rigor has typically been lacking, with many studies relying upon

either symptom counts from a single rating scale or self-report of

prior ADHD diagnoses as the basis for determining participants’

ADHD status. Although co-occurring psychiatric conditions are

common among individuals with ADHD, their presence has either

not been addressed or addressed on a very limited basis. Additional

cross-study differences are evident with respect to the format (i.e.,

group vs. individual) and number (i.e., 3–10) of treatment sessions

offered, as well as the duration of treatment (i.e., 1–3 months).

Furthermore, measures assessing clinical change mechanisms are

rarely included; thus, the conceptual underpinnings of these inter-

ventions are not well understood. Also limited is our understanding

of the persistence of therapeutic improvements beyond active

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

22

ANASTOPOULOS, LANGBERG, EDDY, SILVIA, AND LABBAN

treatment, with only a few studies reporting follow-up assessments

of relatively short duration (i.e., 3 months).

The present study reports findings from a large-scale, multisite

randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining the efficacy of the

CBT program known as ACCESS—Accessing Campus Connec-

tions and Empowering Student Success (Anastopoulos & King,

2015; Anastopoulos et al., 2020). ACCESS incorporates elements

of empirically supported adult CBT programs (Safren et al., 2005;

Solanto, 2011), adapted to the developmental needs of emerging

adults with ADHD in college. ACCESS was originally developed,

refined, and pilot tested in an open clinical trial involving 88

college students with rigorously defined ADHD (Anastopoulos &

King, 2015). An iterative process was used to determine optimal

mode of delivery (e.g., number and length of treatment sessions).

In its current and final form, ACCESS is delivered across two

consecutive semesters, the first of which is an intensive 8-week

active phase, followed by a less intensive semester-long mainte-

nance phase in which treatment is gradually faded. In each phase,

treatment is delivered in both a group and individual mentoring

format. The active phase includes eight weekly group sessions,

each of which is 90 min in length. Concurrent with these group

sessions are weekly individual mentoring sessions, each of which

is approximately 30 min in length. The purpose of individual

mentoring is threefold: to reinforce what the student learns in the

CBT group; to assist the student in establishing personal goals and

monitoring progress; and to help the student make connections

with campus resources as needed (e.g., accommodations, counsel-

ing, medication). As part of the process of fading treatment during

the maintenance phase, one 90-min booster group session is of-

fered at the start of the semester, along with up to six 30-min

individual mentoring sessions that can be scheduled flexibly

throughout the semester at times best meeting participant needs.

Both treatment delivery formats are used to address the goal of

the ACCESS program—namely, to give college students with

ADHD the knowledge and skills necessary to be successful in their

daily life functioning. Specifically, ACCESS is designed to: (a)

give college students a developmentally appropriate understanding

of their own ADHD via a more intensive “dosage” of ADHD

knowledge than is delivered in adult CBT programs (Safren et al.,

2005; Solanto, 2011); (b) improve organization, time management,

and other behavioral strategies that target executive functioning

deficits commonly found among individuals with ADHD; and (c)

increase adaptive thinking skills via cognitive therapy strategies to

address co-occurring depression and anxiety features that are fre-

quently comorbid with ADHD (Anastopoulos et al., 2018). In

contrast with the sequential way in which adult CBT programs

(Safren et al., 2005) deliver these treatment modules (i.e., ADHD

knowledge ¡ behavioral strategies ¡ cognitive therapy),

ACCESS delivers them simultaneously in an integrated fashion,

focused on a common theme (e.g., academic functioning), in each

of the eight active phase group sessions (see Figure 1). The

underlying premise of ACCESS is that improvement in ADHD

knowledge, behavioral strategies, and adaptive thinking skills—

that is, the hypothesized clinical change mechanisms—will facil-

itate improvements in multiple domains of daily life functioning

negatively impacted by ADHD.

Results from our completed open clinical trial revealed statisti-

cally significant improvements in ADHD symptoms, executive

functioning, levels of depression and anxiety, and the number of

semester credit hours attempted and earned (Anastopoulos et al.,

2020). Of note, such improvements were evident at the end of the

active phase and maintained throughout the maintenance phase, 5

to 7 months after treatment started.

The current study builds upon these promising findings and

addresses many of the previously mentioned limitations in the

literature. For example, the current RCT used a large sample of

250 college students with rigorously defined ADHD and comorbid

psychiatric diagnoses drawn from two university settings. Partic-

ipants were randomly assigned either to a group receiving the

ACCESS treatment immediately or to a Delayed Treatment Con-

trol (DTC) condition receiving treatment 1 year later. In contrast

with other CBT programs, ACCESS incorporates concurrent de-

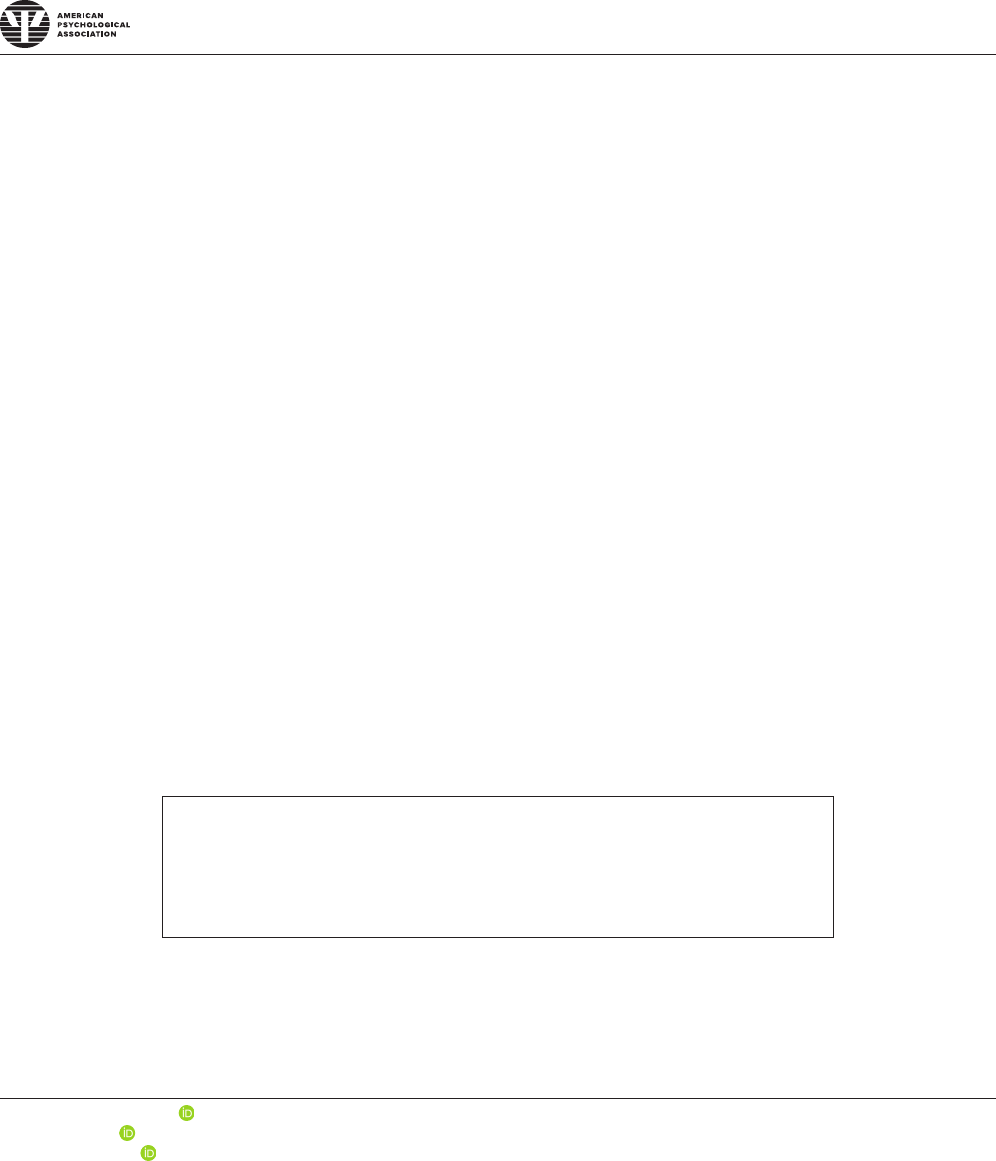

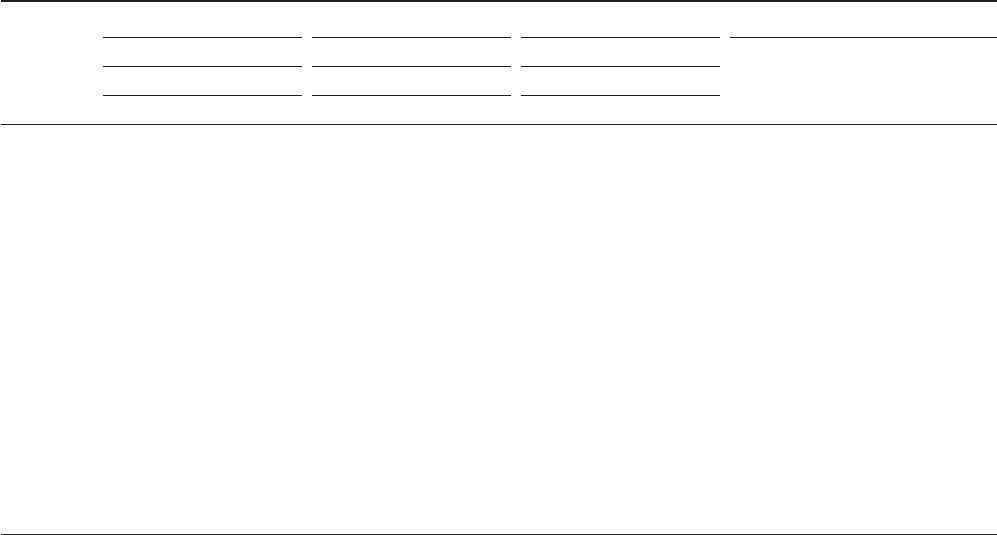

Figure 1

Weekly CBT Group Session Content During the Active Phase of the ACCESS Intervention

Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8

ADHD

Knowledge

Primary

Symptoms

Causes Assessment

School &

Daily

Functioning

Emotions

&Risk-

Taking

Medication

Management

Psychosocial

Treatment

Long-Term

Outlook

Behavioral

Strategies

Campus

Resources

Planners &

To-Do Lists

Getting

Organized

Attending

Classes

Effective

Studying

Long-Term

Projects

Social

Relationships

Long-Term

Goals

Adaptive

Thinking

Basic

Principles

Maladaptive

Thinking

Adaptive

Thinking

Managing

Schoolwork

Handling

Emotions

Adhering to

Treatment

Social

Relationships

Relapse

Prevention

Note. CBT ⫽ cognitive– behavioral therapy; ADHD ⫽ attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

23

CBT FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS WITH ADHD

livery of group and individual sessions, which affords participants

exposure not only to the unique benefits of each treatment modal-

ity, but also to a greater total number of therapeutic contacts (i.e.,

21–25), thereby increasing the intensity of treatment. To better

address the chronic nature of ADHD, participants remain in con-

tact with ACCESS staff for a substantially longer duration (i.e.,

6 –7 months across two semesters) than is offered in similar

interventions. To assess the stability of therapeutic change, out-

come was assessed on three occasions, spanning a full academic

year. Also included were measures of hypothesized clinical change

mechanisms that have direct bearing on the construct validity of

the design.

The purpose of this article is to present RCT findings that

directly address the efficacy of ACCESS across its entire two-

semester long delivery. Given the large number of outcome vari-

ables included in the RCT, the focus of this initial efficacy article

is limited to treatment-induced changes in: (a) primary outcomes

addressing ADHD symptoms, executive functioning (EF), and

co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety, and (b) second-

ary outcomes related to hypothesized clinical change mechanisms

and treatment service utilization. It was hypothesized that, relative

to the DTC condition, participants receiving ACCESS would dis-

play significantly greater improvements in their ADHD symptoms,

EF, co-occurring depression and anxiety symptoms, hypothesized

clinical change mechanisms, and treatment service utilization after

both phases (i.e., active and maintenance) of treatment were com-

pleted. Using reliable change indices (Jacobson & Truax, 1992)to

address the clinical significance of these findings, it was also

expected that higher percentages of ACCESS participants would

show reliable postintervention improvements in these same out-

come domains relative to DTC participants.

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were recruited from two large, public

universities in the southeastern United States that serve large

numbers of first-generation college students and students of color.

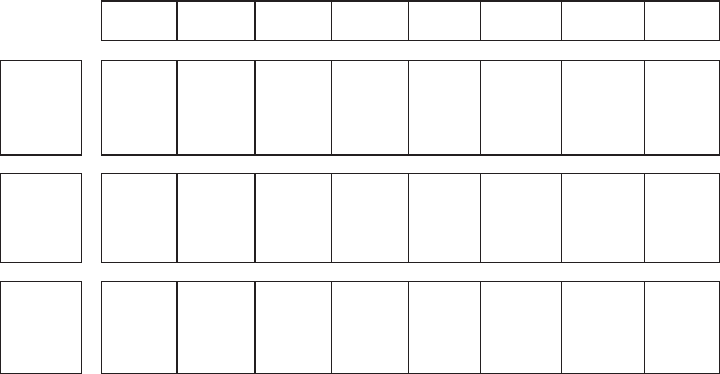

As shown in Figure 2, a total of 361 students were initially

consented into the project and screened for eligibility. Eighty-one

were deemed ineligible, either because they did not meet research

criteria for ADHD or because they displayed a co-occurring psy-

chiatric condition (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder,

obsessive– compulsive disorder) requiring treatment that went be-

yond the scope of the intervention. The remaining 280 participants

meeting eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to receive

ACCESS immediately or on a 1-year delayed basis in the DTC

group. Random assignment was stratified by medication status to

ensure that equivalent numbers of participants taking ADHD med-

ication were assigned to each group condition. Thirty eligible

students assigned to the immediate ACCESS group could not

begin treatment due to class and job schedules that conflicted with

planned group meeting times. This resulted in a final sample of

250 participants, including 165 females (66%) and 85 males

(34%), ranging in age from 18 to 30 years (M ⫽ 19.7, 8.4% ⱖ 23)

and representing a cross-section of postsecondary education levels

(i.e., 47.6% first-year students, 16.4% sophomores, 26.4% juniors,

9.6% seniors). A significant number of these students had experi-

enced academic difficulties prior to enrolling in college, with

26.8% having received at least one D or F grade in high school.

Another 38.4% reported having to work part-time to support

themselves financially while attending college. Approximately

6.8% of the participants reported having Hispanic/Latino back-

grounds; 66.3% identified as Caucasian, 14.2% as African Amer-

ican, 5.3% as Asian, 10.6% as multiracial, and 3.3% as other or not

reported.

A multigating, multimethod, multi-informant assessment ap-

proach (Ramsay, 2015) was used to determine ADHD and comor-

bidity status. Potential participants were initially screened based on

their responses to the ADHD Rating Scale-5 (DuPaul et al., 2016).

Students endorsing four or more symptoms of either inattention

and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity were scheduled for further eval-

uation, which included: a semistructured interview assessing cur-

rent ADHD symptoms and their associated impairment; self-report

rating scales assessing current and childhood symptoms of ADHD;

a structured interview addressing other psychiatric disorders that

may be exclusionary or co-occurring with ADHD; and self-report

ratings of depression and anxiety symptoms. Family, school, and

social background information was also collected, along with prior

mental health evaluation and treatment histories. To increase the

accuracy of addressing the childhood onset criteria, efforts were

made (with consent) to obtain parental ratings of participants’

ADHD symptoms occurring prior to 12 years of age. For a variety

of reasons (e.g., consent withheld, parents not available), it was not

possible to obtain parental ratings for 12.4% of the sample, but this

did not preclude participation in the study. All collected evaluation

data were forwarded to a panel of three ADHD experts (i.e., the

two study principal investigators and a nationally recognized adult

ADHD clinical consultant), who independently reviewed each case

to determine if criteria for ADHD and/or other psychiatric disor-

ders had been met, as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (DSM–5; American

Psychiatric Association, 2013). Final determination of ADHD and

psychiatric comorbidity status required unanimous panel agree-

ment.

Included among the 250 participants in the final sample were

58.4% who received an ADHD Combined presentation diagnosis

and 41.6% who displayed an ADHD Predominantly Inattentive

presentation. Although it was not a requirement for inclusion in the

study, 66.4% of these participants reported having been previously

diagnosed with ADHD; another 24.4% reported histories of being

strongly suspected of having ADHD—that is, significant others

(e.g., parents, teachers, friends) repeatedly raising the possibility

that the participant might have ADHD. Sixty percent also met

DSM–5 criteria for at least one psychiatric diagnosis co-occurring

with ADHD, most often involving a current anxiety or depressive

disorder. For clinical and ethical reasons, students in both condi-

tions could participate in the study regardless of whether they were

receiving other forms of treatment. At the time they were randomly

assigned to a group, nearly half (47.2%) of the participants in the

final sample were taking medication for ADHD; 27.7% were

taking medication for other medical and mental health conditions,

including 10.8% for the treatment of depression and anxiety.

As shown in Table 1, the two groups (immediate ⫽ 119, DTC ⫽

131) were statistically equivalent at pretreatment across these

demographic and clinical variables of interest.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

24

ANASTOPOULOS, LANGBERG, EDDY, SILVIA, AND LABBAN

Diagnostic Measures

Semi-Structured Interview for Adult ADHD

The Semi-Structured Interview for Adult ADHD was devel-

oped specifically for this study because it allowed for a more

thorough and simultaneous assessment of symptoms and

ADHD-specific impairment. For each of the 18 ADHD symp-

toms, respondents rated not only the frequency of occurrence

but also the degree to which there was associated impairment in

daily functioning. In contrast with the fixed way in which

ADHD symptoms are listed in rating scales, interviewers were

allowed to give developmentally appropriate parenthetical de-

scriptions of ADHD symptoms to increase participant under-

standing of the questions being asked. Additional questioning is

directed to the other DSM–5 criteria addressing duration, age of

onset, and exclusionary conditions. Preliminary (unpublished)

analyses indicate that this interview possesses satisfactory re-

liability (coefficient ␣ from .84 to .90) and is highly correlated

with CAARS-S:L symptom dimensions (from .78 to .84). In-

formation from this interview was used in combination with

other assessment data to determine ADHD status.

ADHD Rating Scale-5

The ADHD Rating Scale-5 (ARS-5; DuPaul et al., 2016)isan

18-item questionnaire that possesses excellent reliability (coeffi-

cient ␣ from .89 to .94) and validity and has been used widely in

research and practice. The self-report and parent-report versions of

the ARS-5, which address current functioning, were modified to

include a second column for rating each symptom during child-

hood. Together, these self-report and parent ratings were used to

provide a more specific estimation of the onset and persistence of

ADHD across the life span.

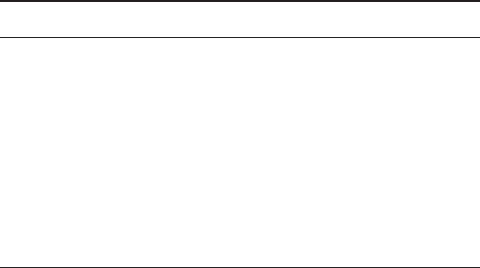

Figure 2

Consort Diagram Showing Flow of Participants Through Clinical Trial. Drop-

Out Rates Were Comparable for the Immediate (20.2%) and Delayed Treatment

Groups (22.1%) at Posttreatment (Postmaintenance Phase). Drop-Outs Did Not

Differ From Completers on Any Pretreatment Demographic, Primary Outcome,

or Secondary Outcome

Assessed for eligibility

(N = 361)

Excluded; did not

meet eligibility

criteria

(n= 81)

Randomized

(n = 280)

Post-treatment

(n = 95)

Assigned to

immediate

intervention

(n= 149)

Assigned to

delayed

intervention

(n= 131)

Post-treatment

(n = 102)

Follow-up

(n = 92)

Enrollment

Attended at least

one treatment

session

(n = 119)

Unable to

participate;

scheduling

conflicts

(n = 30)

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

25

CBT FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS WITH ADHD

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–5: Research

Version (SCID-5-RV)

The SCID-5-RV (First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, 2015)

screeners for the mood, anxiety, trauma, and substance use mod-

ules (coefficient ␣ from .85 to .98) were initially administered to

all participants, after which complete modules were given as

needed for disorders suspected of being present. Information gath-

ered from the SCID-5-RV was used to identify psychiatric condi-

tions that could either rule out an ADHD diagnosis or co-occur

with ADHD, as determined by the expert panel.

Primary Outcome Measures

Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale, Self-Report, Long

Version (CAARS-S:L)

The CAARS-S:L (Conners et al., 2006) is a widely used, psy-

chometrically sound (coefficient ␣ from .73 to .84) measure of

ADHD in adults. The DSM–IV Inattentive (IN), Hyperactive-

Impulsive (HI), and Total scores were used to assess treatment-

related changes in ADHD symptoms.

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Adult

Version (BRIEF-A)

The BRIEF-A (Roth et al., 2005) is a 75-item psychometrically

sound (coefficient ␣⫽.96) self-report measure that generates nine

clinical scales (e.g., Self-Monitoring, Planning, Working Memory,

Emotional Control), as well as three composite scales—the Be-

havior Regulation Index (BRI), Metacognition Index (MCI), and

overall Global Executive Composite (GEC)—which were used to

assess executive functioning (EF) deficits. Higher scores on these

BRIEF-A composite scales indicate poorer EF.

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II)

The BDI-II (Beck et al., 1996) is a psychometrically sound

(coefficient ␣⫽.93) measure of adult depression that is widely

used in research and clinical practice. The BDI-II total score

served as a measure of treatment-induced changes in depressed

mood.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The BAI (Beck & Steer, 1993) is a psychometrically sound

(coefficient ␣⫽.92) measure of anxiety symptoms in adults, used

widely in research and clinical practice. The BAI total score was

used to assess changes in overall levels of anxiety.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Because we were not aware of existing measures for evaluating

hypothesized clinical change mechanisms and participant service

utilization, we assessed these constructs using procedures that we

developed for this and related studies involving college students

with ADHD.

Test of ADHD Knowledge (TOAK)

The TOAK is a 40-item questionnaire that measures general

knowledge of ADHD. For each item, participants respond to

statements about ADHD (e.g., “Hereditary factors play a major

role in determining if someone will develop ADHD”) with

“agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure.” Correctly endorsed “agree” and

“disagree” items are summed to yield a total score, with higher

scores indicating greater knowledge of ADHD. Preliminary (un-

published) findings based on the current sample indicate that the

TOAK possesses excellent internal consistency (coefficient ␣⫽

.86) and demonstrates evidence of convergent validity.

Strategies for Success (SFS)

The SFS contains 18 items that assess self-reported use of

behavioral strategies (e.g., “Doing the most important tasks first”)

for managing academic work in college. Respondents indicate how

adeptly they use these strategies on a 5-point scale, with 1 indi-

cating not well and 5 indicating very well. Items are summed to

yield a total score, with higher scores indicating more frequent

behavioral strategy use. Initial (unpublished) findings from the

current sample suggest that the SFS possesses excellent internal

consistency (coefficient ␣⫽.84).

ADHD Cognitions Scale–College Version (ACS-CV)

The ACS-CV is a 12-item questionnaire that assesses self-

reported frequency of ADHD-related cognitions (e.g., “My work is

better if I wait until the last minute”). Each item is rated on a

5-point scale, and ratings for all 12 items are summed to create a

total ACS-CV score, with higher scores reflecting more frequent

engagement in maladaptive thinking patterns. The ACS-CV uses

many of the same items found in the 7-item ACS developed for

older adult populations (Knouse et al., 2019). For college students,

a psychometrically sound 12-item version was found to be more

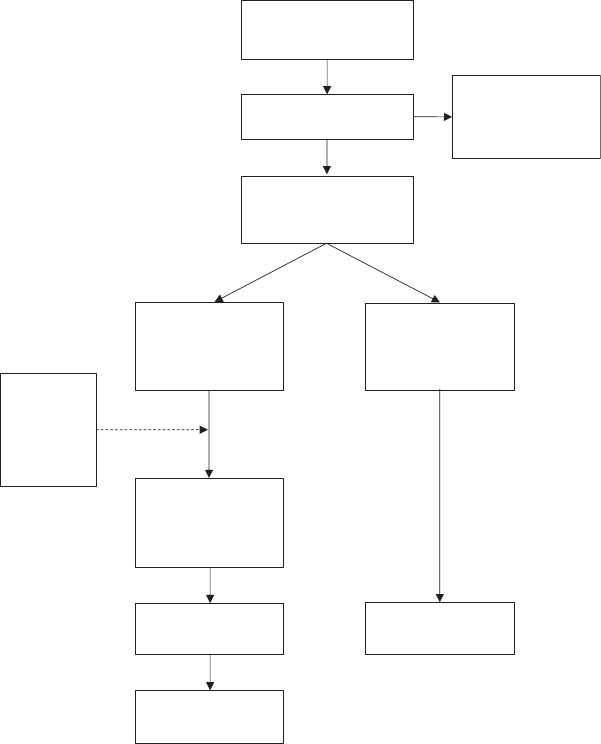

Table 1

Pretreatment Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

by Group

Variable

ACCESS DTC

M (SD) M (SD)

Age (years) 19.7 (2.2) 19.6 (2.1)

CAARS Total ADHD score 34.4 (9.2) 34.7 (8.9)

%%

Sex (female) 64.7 67.2

Race: Caucasian 66.1 66.4

African-American 11.9 16.4

Asian 5.1 5.5

More than one race 11.9 9.4

Other/not reported 5.1 2.4

Ethnicity: Hispanic 7.0 6.6

First year students 49.6 45.8

Comorbidity status 62.2 58.0

ADHD: Combined 58.8 58.0

Predominantly inattentive 41.2 42.0

ADHD medications 53.3 41.7

Other medications 26.1 29.1

Note. ACCESS ⫽ immediate treatment; DTC ⫽ Delayed Treatment

Control; ADHD ⫽ attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CAARS ⫽

Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale; Comorbidity status ⫽ presence of any

non-ADHD psychiatric disorder; ADHD medication status ⫽ reported use

of medication to treat ADHD; Other medication status ⫽ reported use of a

medication to treat other medical/mental health conditions.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

26

ANASTOPOULOS, LANGBERG, EDDY, SILVIA, AND LABBAN

appropriate, with satisfactory internal consistency (coefficient ␣⫽

.77) and evidence of convergent and divergent validity.

Services for College Students Questionnaire (SCSQ)

The SCSQ is a self-report descriptive measure that monitors

participant use of campus support services (e.g., disability accom-

modations) and other treatments (e.g., ADHD medication). For

each service, participants first indicate whether they receive this

service and then provide information about its frequency, duration,

and effectiveness. In this study, participant use of disability ac-

commodations, ADHD medication, medication for other medical/

mental health conditions, and counseling was assessed.

Procedure

Students were recruited from multiple sources, including vari-

ous campus support units (e.g., disability services, student health

services, first-year summer orientation sessions, and campus fli-

ers). All potential participants were made aware that this was a

clinical trial for individuals with ADHD, and that ADHD status

would be evaluated and confirmed prior to entry into the trial.

Interested students contacted the project coordinators at each site

and were initially screened for study eligibility by phone. Poten-

tially eligible participants subsequently underwent a more com-

prehensive evaluation, during which information pertinent to de-

termining eligibility for the study, as well as pretreatment outcome

data, were collected.

Recruitment was ongoing, and ACCESS was delivered to five

successive cohorts of participants across consecutive semesters

from the fall of 2015 through the spring of 2018. Fall cohorts ran

from early September through mid-November; spring cohorts from

early February into mid-April. Treatment outcome data were col-

lected from both groups on three occasions: within 2 weeks prior

to beginning active treatment, immediately after active treatment,

and in the final 2–3 weeks of the maintenance phase semester.

While waiting to participate in ACCESS on a 1-year delayed basis,

DTC participants were permitted to receive treatment as usual.

CBT group and mentoring sessions were conducted in campus-

based clinic settings. Every effort was made to run CBT group

meetings at times that maximized attendance; some students (n ⫽

30) could not participate due to scheduling conflicts (e.g., classes,

jobs). On average, four to six students participated in the CBT

group portion of ACCESS. Groups were conducted using a

discussion-based format to encourage active participation, and

participants received written handouts summarizing important ses-

sion content. Guest speakers from various campus support units

(e.g., disability services, student health) met briefly with the

groups to describe and answer questions about their services.

Mentoring sessions were generally conducted in person within a

few days following the corresponding group session; occasionally,

when in-person sessions were not feasible (e.g., illness), mentoring

was instead conducted by phone.

Graduate student research assistants and one master’s-level li-

censed professional counselor served as group leaders and men-

tors. Prior to being in the study, all received extensive training that

included assigned readings, group discussions, observations, and

role playing. Supervision was provided to group leaders and men-

tors throughout the study by licensed doctoral-level clinical psy-

chologists. Treatment fidelity was further enhanced through use of

a treatment manual containing detailed session-by-session outlines

that guided group leaders and mentors in their delivery of

ACCESS. All treatment sessions were audio recorded, and 20% of

these were randomly selected and reviewed for treatment fidelity

by the group and mentor supervisors. Overall adherence to the

content of treatment sessions was excellent, with fidelity ratings of

96.4 and 95.6% obtained for the group and mentoring sessions,

respectively.

All study procedures were approved annually by each universi-

ty’s Institutional Review Board. In addition to receiving monetary

compensation for completing measures, participants were given a

written summary of their screening evaluation results, which could

be used as documentation for receiving campus support and treat-

ment (e.g., accommodations, medication).

Results

Data Analytic Plan

Latent growth curve models, which allow for analysis of cases

with missing data, were estimated to evaluate how treatment

condition (immediate vs. delayed) influenced change over time.

The models were estimated in Mplus 8.1 using maximum likeli-

hood estimation with robust standard errors, which incorporates a

model-based method for estimating parameters despite missing

data (Enders, 2010). Scores for the three time points (preactive,

postactive, and postmaintenance) served as the indicators. Latent

intercept and slope factors were specified and allowed to covary.

For the intercept, the three factor loadings were set to 1. For the

slope, the first indicator (preactive) was fixed to zero, the second

indicator was freely estimated, and the final indicator (postmain-

tenance) was fixed to 1. In this specification, the intercept value

reflects initial preactive status, and the slope value reflects total

growth from preactive (Time 1, coded 0) to postmaintenance

(Time 3, coded 1).

A multiple-group framework was used to evaluate differential

change over time. The immediate ACCESS and DTC conditions

were specified as the two groups, and Wald tests of model con-

straints were used to test whether the slope means differed signif-

icantly between the two groups. Rarely were there significant

effects of treatment condition on intercept values (i.e., pretreat-

ment scores), consistent with random assignment to condition, and

so these effects were omitted from the main text for clarity.

Because the slopes were constrained to be equal, a significant

model test indicates a rejection of the null hypothesis of equal

slopes in the two group conditions. Within each group, the residual

variances of the intercept and slope, as well as their residual

covariance, were freely estimated. The residual variances of the

slopes tended to be small, and in a handful of cases (e.g., BDI-II)

they were fixed to 0 to facilitate convergence to proper solutions.

The residual variances of the three indicators were constrained to

be equal within each group to reflect homoscedasticity (Preacher et

al., 2008). Initial growth analyses indicated that site differences

had no impact on the trajectories for either group; thus, site was not

included in the final growth models. Model fit for the multiple

group models is displayed in Table 2, with the data reported in the

original, unstandardized metric. Reported below for each outcome

are effect sizes, expressed in the Cohen’s d metric, representing the

magnitude of the difference in slopes between the ACCESS and

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

27

CBT FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS WITH ADHD

DTC conditions (i.e., the effect of condition on change). For the

purposes of interpretation, Cohen’s d values on the order of .20,

.50, and .80 were considered small, medium, and large effects,

respectively.

Primary Outcomes

ADHD Symptoms

The immediate ACCESS (b ⫽⫺6.16, SE ⫽ .82, p ⬍ .001) and

DTC (b ⫽⫺2.90, SE ⫽ .66, p ⬍ .001) groups showed significant

declines in overall ADHD symptomatology as measured by

CAARS Total ADHD scores, with the decline being significantly

greater in the ACCESS condition, Wald (1) ⫽ 9.78, p ⫽ .002, d ⫽

.39 [.15, .65]. The ACCESS (b ⫽⫺4.83, SE ⫽ .52, p ⬍ .001) and

DTC (b ⫽⫺3.32, SE ⫽ .38, p ⬍ .001) groups also showed

significant declines in inattention symptoms as measured by

CAARS IN scores, with a significantly larger decline observed

among ACCESS participants, Wald (1) ⫽ 16.08 p ⬍ .001, d ⫽ .50

[.25, .76]. As shown in Figure S1 (in the online supplemental

materials), these reductions in ADHD symptoms were evident at

the end of the active phase and remained stable throughout the

maintenance phase of the intervention. In contrast with the mar-

ginal decline in hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (CAARS HI

scores) shown by the DTC condition (b ⫽⫺.64, SE ⫽ .34, p ⫽

.060), the ACCESS group showed a significant decline

(b ⫽⫺1.32, SE ⫽ .43, p ⫽ .002); the slopes, however, did not

differ between these groups, Wald (1) ⫽ 1.50, p ⫽ .220, d ⫽ .16

[⫺.09, .41].

Executive Functioning

In terms of overall EF deficits as measured by BRIEF-A GEC

scores, the DTC condition showed a marginal decline

(b ⫽⫺3.31, SE ⫽ 2.02, p ⫽ .101), whereas the immediate

ACCESS group (b ⫽⫺16.69, SE ⫽ 2.28, p ⬍ .001) showed a

significant decline and its slope was significantly greater than

that of the DTC condition, Wald (1) ⫽ 22.32, p ⬍ .001, d ⫽ .56

[.31, .81]. In contrast with the DTC group that displayed no

change in behavioral regulation deficits as measured by

BRIEF-A BRI scores (b ⫽ .14, SE ⫽ .85, p ⫽ .867), the

ACCESS group (b ⫽⫺4.17, SE ⫽ .98, p ⬍ .001) showed a

significant decline and the slopes differed significantly between

the conditions, Wald (1) ⫽ 10.78, p ⫽ .001, d ⫽ .43 [.17, .68].

Regarding metacognition deficits (BRIEF-A MCI scores), there

were significant declines in both the ACCESS group

(b ⫽⫺11.26, SE ⫽ 1.82, p ⬍ .001) and the DTC condition

(b ⫽⫺3.14, SE ⫽ 1.59, p ⫽ .049), but the decline for ACCESS

participants was significantly greater, Wald (1) ⫽ 18.25, p ⬍

.001, d ⫽ .43 [.18, .68]. For all three BRIEF-A measures, these

improvements in EF were evident at the end of the active phase

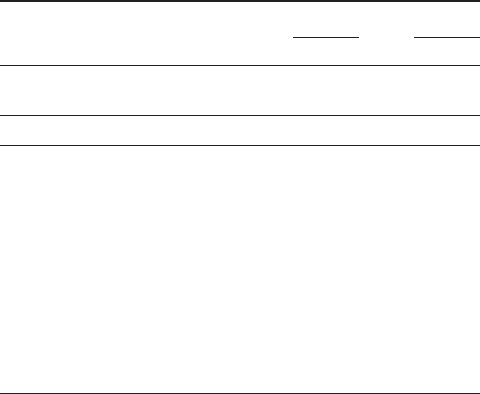

Table 2

Outcome Data and Model Fit Indices

Time 1 Time 2 Time 3 Model fit for multiple group models

Outcome

M (SD) M (SD) M (SD)

2

(df) CFI SRMR

RMSEA

[90% CI]

nnn

ACCESS DTC ACCESS DTC ACCESS DTC

CAARS Total 34.48 (9.16) 34.73 (8.82) 29.64 (9.28) 31.54 (10.43) 28.46 (9.48) 31.68 (9.48) 9.31 (7) .99 .12 .05 [.00, .13]

117 130 111 109 95 102

IN 19.93 (4.57) 20.36 (4.45) 16.25 (5.20) 18.22 (5.70) 15.05 (5.24) 17.86 (5.28) 16.22 (7) .94 .20 .10 [.04, .17]

117 130 111 109 95 102

HI 14.55 (5.74) 14.37 (5.61) 13.39 (5.32) 13.32 (6.23) 13.41 (5.57) 13.81 (5.89) 3.87 (5) 1 .06 .00 [.00, .11]

117 130 111 109 95 102

BRIEF GEC 157.17 (18.13) 155.62 (22.30) 145.86 (25.05) 154.00 (24.46) 140.39 (24.85) 150.01 (24.69) 9.09 (7) .98 .25 .05 [.00, .13]

118 131 113 111 93 100

BRI 60.70 (11.22) 59.40 (11.05) 58.02 (12.28) 59.85 (11.95) 56.88 (11.86) 59.06 (11.95) 3.38 (7) 1 .10 .00 [.00, .06]

118 131 113 111 93 100

MCI 95.62 (14.71) 95.87 (14.84) 87.58 (15.23) 94.15 (15.18) 83.51 (15.07) 90.93 (15.48) 7.05 (5) .96 .07 .06 [.00, .15]

118 131 113 111 93 100

BDI-II 14.60 (10.55) 14.82 (10.57) 12.97 (9.98) 18.47 (11.97) 13.12 (11.39) 16.19 (11.62) 7.80 (7) .99 .08 .03 [.00, .12]

119 131 113 113 95 103

BAI 13.67 (11.79) 12.15 (10.29) 14.32 (11.40) 14.65 (11.38) 12.27 (10.53) 14.29 (12.04) 8.28 (5) .98 .03 .07 [.00, .16]

119 131 113 113 94 102

TOAK 20.86 (6.19) 20.85 (6.23) 29.93 (4.86) 22.70 (5.68) 29.03 (5.00) 23.15 (5.63) 17.91 (5) .93 .08 .14 [.08, .22]

119 129 113 110 94 103

SFS 46.74 (10.97) 44.74 (11.00) 61.16 (11.64) 48.84 (12.09) 61.18 (12.27) 49.58 (13.58) 6.33 (5) .99 .09 .05 [.00, .14]

119 131 112 113 93 104

ACS-CV 36.27 (7.88) 36.03 (8.23) 32.93 (7.84) 35.77 (7.91) 31.91 (8.13) 35.54 (8.71) 4.43 (5) 1 .07 .00 [.00, .12]

119 131 110 113 95 103

Note. Outcome data reported in the original, unstandardized metric; CFI ⫽ comparative fit index; SRMR ⫽ standardized root mean square residual;

RMSEA ⫽ root mean square error of approximation; ACCESS ⫽ immediate treatment; DTC ⫽ Delayed Treatment Control; CAARS total ⫽ Conners Adult

ADHD Rating Scale total score; IN ⫽ CAARS inattention; HI ⫽ CAARS hyperactivity-impulsivity; BRIEF GEC ⫽ Behavioral Rating Inventory of

Executive Functioning Global Executive Composite; BRI ⫽ BRIEF Behavior Regulation Index; MCI ⫽ BRIEF Metacognition Index; BDI-II ⫽ Beck

Depression Inventory–II; BAI ⫽ Beck Anxiety Inventory; TOAK ⫽ Test of ADHD Knowledge; SFS ⫽ Strategies for Success; ACS-CV ⫽ ADHD

Cognitions Scale–College Version.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

28

ANASTOPOULOS, LANGBERG, EDDY, SILVIA, AND LABBAN

and remained stable throughout the maintenance phase of AC-

CESS (see Figure S2 in the online supplemental materials).

Emotional Functioning

Analyses of the BDI-II revealed no significant reductions in

depression symptoms for either the ACCESS (b ⫽⫺.77, SE ⫽

.74, p ⫽ .297) or DTC groups (b ⫽ 1.81, SE ⫽ 1.14, p ⫽ .111),

and the slopes did not differ significantly, Wald (1) ⫽ 2.13, p ⫽

.145, d ⫽ .24 [⫺.01, .49]. Analyses of BAI scores indicated that

there was a significant increase in anxiety for the DTC group (b ⫽

2.78, SE ⫽ .98, p ⫽ .005), but no change in the ACCESS condition

(b ⫽⫺1.10, SE ⫽ 1.16, p ⫽ .346); the slopes between groups

differed significantly, Wald (1) ⫽ 6.22, p ⫽ .013, d ⫽ .33 [.08,

.58]. Although emotional functioning did not improve, it is of

clinical interest to note that depression and anxiety levels seemed

to stabilize for ACCESS participants, while worsening for DTC

participants (see Figure S3 in the online supplemental materials).

Secondary Outcomes

Clinical Change Mechanisms

The immediate ACCESS (b ⫽ 8.29, SE ⫽ .53, p ⬍ .001) and

DTC (b ⫽ 1.99, SE ⫽ .41, p ⬍ .001) groups showed significant

growth in their knowledge of ADHD as measured by TOAK

scores. This increase in ADHD knowledge was significantly

greater among ACCESS participants, Wald (1) ⫽ 102.24, p ⬍

.001, d ⫽ 1.21 [.94, 1.48]. The immediate ACCESS (b ⫽ 14.50,

SE ⫽ 1.33, p ⬍ .001) and DTC (b ⫽ 4.11, SE ⫽ .97, p ⬍ .001)

groups also showed significant growth in their use of behavioral

strategies as measured by SFS scores, with the increase being

significantly larger in the ACCESS condition, Wald (1) ⫽ 42.24,

p ⬍ .001, d ⫽ .81 [.56, 1.07]. Analyses of maladaptive thinking as

measured by ACS-CV scores indicated that the DTC group did not

significantly change over time (b ⫽⫺.44, SE ⫽ .63, p ⫽ .487).

The ACCESS condition did change significantly over time

(b ⫽⫺4.24, SE ⫽ .74, p ⬍ .001), and this decline in maladaptive

thinking was significantly greater for the immediate ACCESS

participants, Wald (1) ⫽ 15.57, p ⬍ .001, d ⫽ .50 [.25, .75]. As

shown in Figure S4 (in the online supplemental materials), these

improvements in clinical change mechanisms were evident at the

end of the active phase and remained stable throughout the main-

tenance phase of ACCESS.

Service Utilization

A descriptive summary of participants’ use of treatment and

other support services appears in Table 3. Because these outcomes

are categorical, scored 0 and 1, an alternate model specification

was used. Growth curve models with categorical indicators do not

afford the same markers of model fit and estimating a multiple-

group model is much less straightforward for categorical out-

comes. As before, latent intercept (1, 1, 1) and slope (0,

ⴱ

,1)

factors were estimated, and the residual variances and covariance

for the intercept and slope were freely estimated. Treatment con-

dition was included as an observed predictor (coded 0 ⫽ delayed,

1 ⫽ immediate). This model thus estimates the overall slope for

the entire sample, along with how treatment status predicts varia-

tion in the slope.

The sample overall did not change in its use of disability service

accommodations over time, b ⫽ .39, SE ⫽ .49, p ⫽ .415, but

treatment status significantly moderated change, with the imme-

diate ACCESS condition showing a significant increase in using

disability services, b ⫽ 1.96, SE ⫽ .58, p ⫽ .001, d ⫽ 1.03 [.48,

1.59]. Although the sample overall increased its use of ADHD

medication, b ⫽ 3.16, SE ⫽ 1.39, p ⫽ .022, treatment status did

not significantly moderate this change, b ⫽⫺.81, SE ⫽ 1.24, p ⫽

.513, d ⫽ .18 [⫺.32, .68]. There was no change in overall sample

use of medications for other medical and mental health conditions,

b ⫽ 1.36, SE ⫽ 12.00, p ⫽ .910, and treatment status did not

significantly moderate the slope, b ⫽⫺.58, SE ⫽ 1.75, p ⫽ .740,

d ⫽ .25 [⫺1.02, 1.52]. Likewise, the sample overall did not change

in its use of counseling services delivered outside of ACCESS,

b ⫽⫺.20, SE ⫽ .28, p ⫽ .468, and treatment status did not

significantly moderate the slope, b ⫽⫺.03, SE ⫽ .20, p ⫽ .900,

d

⫽ .13 [⫺1.40, 1.66].

Clinical Significance of Findings

To inform clinical practice, reliable change indices (RCI; Ja-

cobson & Truax, 1992) were calculated to determine individual

rates of response to treatment. Preactive to postmaintenance phase

difference scores were used for these calculations, with positive

differences reflecting desired therapeutic change for all outcome

measures. Consistent with the Jacobson and Truax (1992) guide-

lines, RCIs greater than 1.96 represented evidence of statistically

significant improvement. Although positive RCIs ⱕ1.96 can re-

flect improvement, these changes are not of a magnitude to be

considered statistically significant and therefore are likely due to

chance. Because individuals with ADHD are at increased risk for

displaying deterioration in their functioning (Barkley, 2015), a

third clinical significance category was generated, operationally

defined as RCIs ⬍0, to examine outcomes reflecting a worsening

in functioning over time.

Higher rates of reliable improvement among immediate

ACCESS participants were revealed by

2

analyses of the ob-

Table 3

Service Utilization by Group Over Time

Service % Preactive % Postactive % Postmaintenance

Disability services

ACCESS 25.3 67.3 60.9

DTC 22.1 37.5 38.0

ADHD medication

ACCESS 53.3 68.9 67.0

DTC 41.7 59.4 71.9

Other medication

ACCESS 26.1 24.0 30.1

DTC 29.1 32.4 37.6

Counseling services

ACCESS 33.7 25.3 34.5

DTC 52.4 39.4 45.1

Note. Disability services ⫽ use of formal disability accommodations

approved by campus disability office; ACCESS ⫽ immediate treatment;

DTC ⫽ Delayed Treatment Control; ADHD ⫽ attention deficit/

hyperactivity disorder; ADHD medication ⫽ use of medication to treat

ADHD; Other medication ⫽ use of medication to treat other mental health

and medical conditions; Counseling services ⫽ use of counseling received

outside of ACCESS program.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

29

CBT FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS WITH ADHD

served RCI distributions (see Table 4), in terms of inattention (61.3

vs. 31.4%), EF (50.5 vs. 30.0%), anxiety (10.6 vs. 2.0%), knowl-

edge of ADHD (43.6 vs. 8.8%), and use of behavioral strategies

(31.2 vs. 10.2%). Although rates of reliable improvement were

essentially equivalent for immediate ACCESS and DTC partici-

pants with respect to depression and maladaptive thinking patterns,

higher percentages of DTC participants displayed a worsening in

their reports of both depression (54.4 vs. 37.9%) and maladaptive

thinking (41.7 vs. 23.2%). Further evidence of this increased risk

for a deterioration in functioning among DTC versus immediate

ACCESS participants was also seen among the distributions for

inattention (22.5 vs. 12.9%), EF (40.0 vs. 22.6%), anxiety (52.0 vs.

42.6%), knowledge of ADHD (22.5 vs. 5.3%), and behavioral

strategy use (27.6 vs. 9.7%).

Discussion

Findings from this large-scale multisite RCT revealed numerous

improvements in functioning among the college students with

ADHD who received ACCESS on an immediate versus delayed

basis. In terms of primary outcomes, immediate ACCESS partic-

ipants displayed statistically significant greater declines in their

overall ADHD symptomatology, which was driven largely by a

decline in their self-reported inattention symptoms. Effect sizes

associated with these differences were medium in strength (Co-

hen’s d ranging from .39 to .50). Immediate ACCESS participants

also displayed statistically significant improvements in executive

functioning (EF), with medium effect sizes noted for overall EF

deficits (d ⫽ .56), as well as for EF deficits pertaining specifically

to behavioral regulation (d ⫽ .43) and metacognition (d ⫽ .43)

skills. Contrary to study expectations, neither group exhibited a

statistically significant decline in overall levels of depression.

Although immediate ACCESS participants did not show a signif-

icant decline in overall levels of anxiety, there was a significant

increase in anxiety for the DTC group. The slopes between the two

groups were significantly different, thus suggesting a significant

worsening of anxiety symptoms among DTC participants.

Examination of hypothesized mechanisms of clinical change

and participant service utilization also revealed statistically signif-

icant differences between the groups. Although both groups

showed increases over time in their knowledge of ADHD and use

of behavioral strategies, these increases were significantly greater

for participants in the immediate ACCESS group versus the DTC

condition. Effect sizes associated with these group differences

were large, with Cohen’s d estimates of 1.21 and .81 for ADHD

knowledge and behavioral strategies, respectively. The immediate

ACCESS group also displayed a significantly greater decline in

maladaptive thinking than the DTC condition, with the difference

between the groups being of moderate effect size (d ⫽ .50). Such

improvements in ADHD knowledge, use of behavioral strategies,

and adaptive thinking skills, as measured by our study-specific

measures, speak to their potential role as clinical change mecha-

nisms, lending support to the construct validity of our design. In

terms of service utilization, group status moderated use of disabil-

ity services, with immediate ACCESS participants displaying a

significant increase in their use of disability accommodations.

Both groups exhibited significantly increased use of ADHD med-

ications over time, but this increase was not moderated by group

status. The fact that both groups increased their use of ADHD

medication may have been facilitated by participants’ receipt of

written screening evaluation summaries that could be used as

documentation for receiving such services. Neither group, how-

ever, displayed statistically significant increases in their use of

medication for other mental health conditions or in their partici-

pation in counseling outside of ACCESS.

Our clinical significance analyses, which address therapeutic

change at the level of individuals rather than group aggregates,

also revealed findings in line with study expectations. Relative to

DTC participants, higher percentages of immediate ACCESS par-

ticipants displayed reliable improvements in multiple domains of

functioning, including self-reported inattention symptoms, execu-

tive functioning, anxiety symptoms, knowledge of ADHD, and use

of behavioral strategies. Of additional clinical significance are

findings at the other end of the continuum. Specifically, higher

percentages of DTC participants displayed a worsening in their

functioning relative to immediate ACCESS participants in terms of

inattention, executive functioning, depression, anxiety, knowledge

of ADHD, behavioral strategy use, and maladaptive thinking. Such

evidence of a deterioration in functioning is not completely unex-

pected, given what is known about the deleterious impact of

ADHD across the life span (Barkley, 2015). What is surprising,

and at the same time sobering, is the magnitude of the worsening

and the fact that it occurred within a relatively short 12-month time

frame among DTC participants who could and did receive treat-

ments other than ACCESS (e.g., ADHD medication).

Although it is clinically meaningful that ACCESS participants

were less likely to experience a worsening in their depression and

Table 4

Treatment Response Classifications Based on Reliable

Change Indices

Outcome % Worse % Improved

% Reliable

improvement

2

CAARS IN

ACCESS 12.9 25.8 61.3 17.55

ⴱⴱⴱ

DTC 22.5 46.1 31.4

BRIEF-A GEC

ACCESS 22.6 26.9 50.5 9.89

ⴱⴱ

DTC 40.0 30.0 30.0

BDI-II Total

ACCESS 37.9 41.1 21.1 6.22

ⴱ

DTC 54.4 26.2 19.4

BAI Total

ACCESS 42.6 46.8 10.6 6.93

ⴱ

DTC 52.0 46.1 2.0

TOAK Total

ACCESS 5.3 51.1 43.6 35.89

ⴱⴱⴱ

DTC 22.5 68.6 8.8

SFS Total

ACCESS 9.7 58.1 31.2 18.45

ⴱⴱⴱ

DTC 27.6 62.2 10.2

ACS-CV Total

ACCESS 23.2 65.3 11.6 8.07

ⴱ

DTC 41.7 51.5 6.8

Note. CAARS IN ⫽ Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale Inattention;

DTC ⫽ Delayed Treatment Control; BRIEF-A GEC ⫽ Behavioral Rating

Inventory of Executive Functioning–Adults Global Executive Composite;

BDI-II ⫽ Beck Depression Inventory; BAI ⫽ Beck Anxiety Inventory;

TOAK ⫽ Test of ADHD Knowledge; SFS ⫽ Strategies for Success;

ACS-CV ⫽ ADHD Cognitions Scale–College Version.

ⴱ

p ⬍ .05.

ⴱⴱ

p ⬍ .01.

ⴱⴱⴱ

p ⬍ .001.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

30

ANASTOPOULOS, LANGBERG, EDDY, SILVIA, AND LABBAN

anxiety symptoms according to the RCI results, their failure to

improve in these domains was somewhat surprising. This lack of

improvement could be due to the timing of when the adaptive

thinking portion of ACCESS directly addresses emotional func-

tioning. Because this occurs in Week 5 of the 8-week active phase

(see Figure 1), ACCESS participants may not have had enough

time to master the adaptive thinking skills necessary for bringing

about improvements in depression and anxiety. Assuming this to

be the case, one option for addressing this would be to identify

participants with elevated pretreatment levels of depression/anxi-

ety and to have mentors begin targeting these emotional features at

an earlier stage of ACCESS. Mentors could also encourage de-

pressed/anxious participants to seek out and concurrently receive

more intensive individual CBT counseling outside of ACCESS.

Such recommendations are in keeping with the notion that ADHD

is best managed via multimodal interventions (Barkley, 2015). In

this regard, ACCESS is well suited to being used in combination

with other treatments (e.g., medication, accommodations, counsel-

ing) to address the multiple psychosocial needs of emerging adults

with ADHD attending college.

Despite the encouraging nature of the obtained findings, it

remains necessary to acknowledge limitations that have bearing on

conclusions drawn from this RCT. For example, the primary and

secondary outcome measures reported in this article were some-

what limited in scope and based exclusively on self-report. As

noted earlier, our RCT did include measures examining other

outcomes (e.g., academic, general daily functioning) but space

limitations precluded their inclusion in the current article. These

will be addressed subsequently, including analyses of more objec-

tive measures of academic functioning drawn from educational

records (see Appendix). Two additional issues not addressed in

this article are: (a) the temporal stability of treatment-induced

improvements following termination from ACCESS, and (b) the

potential moderating effects of sex/gender, race/ethnicity, and

variables of clinical interest (e.g., comorbid features) on response

to treatment. Both issues will be thoroughly examined in a subse-

quent article focused on the treatment response of immediate

ACCESS participants, for whom outcome data are available not

only from the active and maintenance phases, but also from a

follow-up assessment (see Figure 2) conducted 6 months after

participation in ACCESS had been completed. The fact that im-

mediate and delayed treatment participants could receive other

forms of treatment while participating in the study makes it diffi-

cult to ascertain the unique contribution that ACCESS made to

observed improvements in outcome. Evidence indirectly suggest-

ing that ACCESS did indeed contribute to treatment gains may be

inferred from the absence of group differences in their use of other

treatments (i.e., ADHD medication, medication for other mental

health conditions, counseling services). Another potential limita-

tion affecting the external validity of these findings is the gender

distribution of our sample (66% female), which differs from the

relatively higher proportion of males known to have ADHD in the

general population. The reasons for this discrepancy are not en-

tirely clear, but it is first important to note that the gender distri-

bution of our sample is in line with the 60 – 67% representation of

female undergraduates at our two sites. Also speaking to this issue

is the fact that longitudinal research has shown that females with

ADHD generally attain more years of formal education than do

males with this same condition (Barkley et al., 2008).

Bearing these limitations in mind, findings from this large

multisite RCT study build upon those reported from our earlier

open clinical trial (Anastopoulos & King, 2015; Anastopoulos et

al., 2018) and provide strong evidence in support of the efficacy of

ACCESS as a treatment for emerging adults with ADHD attending

college. Although ACCESS shares features found in other psycho-

social treatments for college students with ADHD (e.g., CBT,

OTMP, coaching), it uniquely blends many of these components

together into a single treatment package that is further enhanced by

the inclusion of novel treatment elements, such as: an intensive

ADHD knowledge component to give college students a develop-

mentally appropriate understanding of their own ADHD; simulta-

neous delivery of group treatment and individual mentoring to

facilitate acquisition and mastery of new knowledge and skills; and

a longer duration of treatment (i.e., active and maintenance phases

delivered across two semesters) to better address the chronic

nature of ADHD. Given the clinically challenging nature of the

college students in the study and the rigor with which ADHD and

comorbid conditions were identified in our multisite sample, it is

likely that ACCESS is well-suited to addressing the needs of other

students with ADHD in postsecondary settings. Its feasibility as a

treatment option stems in part from a consideration of the fact that

participation in ACCESS was quite high during the active treat-

ment phase: 83.2% attended at least six of eight planned group

sessions; 85.7% attended a comparable number of mentoring ses-

sions. Also speaking to its feasibility is that ACCESS was imple-

mented in two different university settings with the strong support

of campus support staff. Thus, our findings represent an important

first step in closing the gap from research to practice. Left to future

research is the task of determining how effectively ACCESS can

be disseminated in other college settings, especially those in which

resources (e.g., disability services) and staffing (e.g., level of

ADHD expertise) may differ from those of the two sites in the

current study, thereby potentially requiring minor changes in staff

training and program implementation.

In conclusion, college students with ADHD are at increased risk

for a multitude of educational and psychosocial difficulties that

have serious personal, institutional, and public health implications,

not only during college, but also during the transition into a

postcollege world where demands for self-regulation are greater.

To reduce this risk, it is important for college students with ADHD

to have ready access to evidence-based treatment. Building on the

results of our open clinical trial, findings from the current RCT

suggest that ACCESS is a promising new evidence-based treat-

ment that can play an important role in the overall clinical man-

agement of college students with ADHD.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical man-

ual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Anastopoulos, A. D., DuPaul, G. J., Weyandt, L. L., Morrissey-Kane, E.,

Sommer, J. L., Rhoads, L. H., Murphy, K. R., Gormley, M. J., &

Gudmundsdottir, B. G. (2018). Rates and patterns of comorbidity among

first-year college students with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and

Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 236 –247. https://doi.org/10.1080/

15374416.2015.1105137

Anastopoulos, A. D., & King, K. A. (2015). A cognitive-behavior therapy

and mentoring program for college students with ADHD. Cognitive and

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

31

CBT FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS WITH ADHD

Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra

.2014.01.002

Anastopoulos, A. D., King, K. A., Besecker, L. H., O’Rourke, S. R., Bray,

A. C., & Supple, A. J. (2020). Cognitive-behavior therapy for college

students with ADHD: Temporal stability of improvements in function-

ing following active treatment. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(6),

863– 874. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717749932

Antshel, K. M., Hier, B. O., & Barkley, R. A. (2014). Executive function-

ing theory and ADHD. In S. Goldstein & J. A. Naglieri (Eds.), Hand-

book of executive functioning (pp. 107–120). Springer. https://doi.org/

10.1007/978-1-4614-8106-5_7

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good

for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68 –73. https://doi.org/10

.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x

Barkley, R. A. (2015). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook

for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

Barkley, R. A., Murphy, K. R., & Fischer, M. (2008). ADHD in adults:

What the science says. Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck Anxiety Inventory manual.

Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A., Steer, R., & Brown, G. (1996). BDI-II, Beck Depression Inven-

tory: Manual (2nd ed.). Psychological Corporation.

Blasé, S. L., Gilbert, A. N., Anastopoulos, A. D., Costello, E. J., Hoyle,

R. H., Swartzwelder, H. S., & Rabiner, D. L. (2009). Self-reported

ADHD and adjustment in college: Cross-sectional and longitudinal

findings. Journal of Attention Disorders, 13(3), 297–309. https://doi.org/

10.1177/1087054709334446

Conners, C. K., Erhardt, D., & Sparrow, E. (2006). Conners’ Adult ADHD

Rating Scales. Multi-Health Systems.

DuPaul, G. J., Franklin, M. K., Pollack, B. L., Stack, K. S., Jaffe, A. R.,

Gormley, M. J., Anastopoulos, A. D., & Weyandt, L. L. (2018). Pre-

dictors and trajectories of educational functioning in college students

with and without ADHD. Journal of Postsecondary Education and

Disability, 31(2), 161–178.

DuPaul, G. J., Power, T. J., Anastopoulos, A. D., & Reid, R. (2016). ADHD

Rating Scale-5 for children and adolescents: Checklists, norms, and

clinical interpretation. Guilford Press.

DuPaul, G. J., Weyandt, L. L., Rossi, J. S., Vilardo, B. A., O’Dell, S.,

Carson, K. M., Verdi, G., & Swentosky, A. (2012). Double-blind,

placebo-controlled, crossover study of the efficacy and safety of lisdex-

amfetamine dimesylate in college students with ADHD. Journal of

Attention Disorders, 16(3), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1087054711427299

Eagan, K., Stolzenberg, E. B., Ramirez, J. J., Aragon, M. C., Suchard,

M. R., & Hurtado, S. (2014). The American freshman: National norms

fall 2014. Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press.

First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S., & Spitzer, R. L. (2015).

Structured clinical interview for DSM–5–Research version (SCID-5-

RV). American Psychiatric Association.

Fleming, A. P., & McMahon, R. J. (2012). Developmental context and

treatment principles for ADHD among college students. Clinical Child

and Family Psychology Review, 15, 303–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s10567-012-0121-z

Fleming, A. P., McMahon, R. J., Moran, L. R., Peterson, A. P., &

Dreessen, A. (2015). Pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical

behavior therapy group skills training for ADHD among college stu-

dents. Journal of Attention Disorders

, 19(3), 260 –271. https://doi.org/

10.1177/1087054714535951

Gormley, M. J., DuPaul, G. J., Weyandt, L. L., & Anastopoulos, A. D.

(2019). First-year GPA and academic service use among college stu-

dents with and without ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(14),

1766 –1779. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715623046

Gu, Y., Xu, G., & Zhu, Y. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of

mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for college students with ADHD.

Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(4), 388 –399. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1087054716686183

He, J., & Antshel, K. (2017). Cognitive behavioral therapy for attention

deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in college students: A review of

the literature. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 24(2), 152–173.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.03.010

Hechtman, L. (2017). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Adult out-

come and its predictors. Oxford University Press.

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1992). Clinical significance: A statistical

approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. In

A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Methodological issues & strategies in clinical

research (pp. 631– 648). American Psychological Association. https://

doi.org/10.1037/10109-042

Knouse, L. E., Mitchell, J. T., Kimbrel, N. A., & Anastopoulos, A. D.

(2019). Development and evaluation of the ADHD Cognitions Scale for

adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(10), 1090–1100. https://doi

.org/10.1177/1087054717707580

LaCount, P. A., Hartung, C. M., Shelton, C. R., Clapp, J. D., & Clapp,

T. K. (2015). Preliminary evaluation of a combined group and individual

treatment for college students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disor-

der. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 152–160. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.07.004

LaCount, P. A., Hartung, C. M., Shelton, C. R., & Stevens, A. E. (2018).

Efficacy of an organizational skills intervention for college students with