A Cognitive-Behavior Therapy and Mentoring Program for College Students With ADHD

By: Arthur D. Anastopoulos and Kristen A. King

Anastopoulos, A.D. & King, K.A. (2015). A cognitive-behavior therapy and mentoring program

for college students with ADHD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 141-151. DOI:

10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.002

Made available courtesy of Elsevier: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.002

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Abstract:

College students with ADHD are at increased risk for a number of functional impairments, the

severity of which is of sufficient clinical significance to warrant intervention (DuPaul &

Weyandt, 2009). Very little treatment research of this type has been conducted to date (Green &

Rabiner, 2012). The need for such research is critical, given the increasing numbers of students

with ADHD attending college (Pryor, Hurtado, DeAngelo, Blake, & Tran, 2010), their increased

risk for dropping out of college, and the known negative life outcomes for which they may be at

increased risk later as adults (Barkley, Murphy, & Fischer, 2008). To address this situation we

recently developed and began testing Accessing Campus Connections and Empowering Student

Success (ACCESS). The active phase of ACCESS provides group cognitive behavior therapy

(CBT), accompanied by individual mentoring. Booster group CBT and mentoring sessions are

provided during a maintenance phase. Preliminary findings have revealed significant increases in

ADHD knowledge, use of organizational skills, and reductions in maladaptive thinking, all of

which are presumed mechanisms of clinical change. Such changes have been accompanied by

reductions in ADHD symptoms, improvements in executive functioning, educational benefits,

improved emotional well-being, and increased use of disability services and other campus

resources. Although promising, such findings are limited by the fact that ACCESS has thus far

been tested in an open clinical trial. Thus, additional research is needed to determine its efficacy

and effectiveness.

Keywords: adult ADHD | college students | clinical trial | psychosocial intervention | cognitive-

behavior therapy

Article:

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a chronic life-span condition

associated with long-term impairment in educational attainment, occupational status, and social

relationships, as well as increased risk for psychopathology and legal difficulties (Barkley,

Murphy, & Fischer, 2008; Mannuzza, Gittelman-Klein, Bessler, Malloy, & LaPadula, 1993).

Individuals identified as having ADHD in childhood are significantly less likely to graduate from

high school. Significantly fewer (20–21%) go on to college relative to their non-ADHD peers

(68–78%; Barkley et al., 2008).

Although the exact prevalence of individuals with ADHD attending college is not well

established, estimates derived from large sample studies indicate that approximately 2 to 8% of

college students report clinically significant symptoms of ADHD (DuPaul et al., 2001; McKee,

2008; Norvilitis, Ingersoll, Zhang, & Jia, 2008). Consistent with these estimates are the results of

a recently conducted national survey, which revealed that 5% of incoming first-year students

reported having ADHD (Pryor, Hurtado, DeAngelo, Blake, & Tran, 2010). Also, among college

students who receive disability accommodations, approximately 25% receive such services on

the basis of an ADHD diagnosis (Wolf, 2001). Thus, clinically significant ADHD symptoms

would appear to affect a substantial segment of the college population.

As is true for children and adults, the impact of ADHD on the daily and long-term

functioning of college students with ADHD is clinically significant and broad in nature. In terms

of educational functioning, it has been reported that college students with ADHD maintain lower

grade point averages (GPAs), withdraw from a greater number of courses, and take longer to

complete their degree programs relative to control individuals without ADHD (Barkley et al.,

2008). Of additional clinical and public health significance, Barkley and his colleagues (2008)

found that only 9.1% of individuals who display ADHD in young adulthood actually graduate

from college compared to 60.6% of the non-ADHD control group. Impairment in psychological

and social functioning may occur as well, with many studies indicating that college students with

ADHD are more likely to experience higher levels of depression, anxiety, and other types of

psychological distress (e.g., Heiligenstein & Keeling, 1995; Rabiner, Anastopoulos, Costello,

Hoyle, & Swartzwelder, 2008; Weyandt et al., 2003), and to display lower levels of overall

adjustment, social skills, and quality of life (Grenwald-- Mayes, 2002; Shaw-Zirt, Popali-Lehane,

Chaplin, & Bergman, 2005). A handful of studies has explored the driving performance of

college students with ADHD and the results consistently indicate that students with ADHD have

a higher number of driving citations, speeding violations, license suspensions/revocations, and

motor vehicle accidents relative to non-ADHD peers (Barkley, Murphy, DuPaul, & Bush, 2002;

Richards, Deffenbacher, & Rosén, 2002). Preliminary findings also suggest that college students

with ADHD may be at higher risk for substance abuse relative to non-ADHD controls (Kollins,

2008; Upadhyaya et al., 2005).

Conceptual Model for Understanding Impairment

The degree to which college students with ADHD experience impairment may seem

counterintuitive at some level, given that such individuals possessed the qualifications necessary

to be admitted to college (Glutting, Youngstrom, & Watkins, 2005). Some researchers have

speculated that inadequate educational coping strategies, poor organizational and study skills,

and inefficient time management may underlie these difficulties (e.g., Heiligenstein, Guenther,

Levy, Savino, & Fulwiler, 1999; Norwalk, Norvilitis, & MacLean, 2008; Reaser, Prevatt,

Petscher, & Proctor, 2007; Weyandt et al., 2003). Yet another possible explanation stems from a

theoretical consideration of what could be termed a “perfect storm” of circumstances that

converge upon students with ADHD as they enter college. Prior to college, many supports may

be in place to help manage the deficits in self-regulation (Barkley, 2006) that a student with

ADHD might display. Such supports might include, for example, an individualized educational

plan or 504 accommodations in school, regular use of pharmacotherapy to address school--

related ADHD difficulties, and parental monitoring of school work loads, upcoming tests, and

assignment due dates. Parental supervision may also extend into nonacademic domains, thereby

relieving the student of the responsibility of managing finances, daily schedules, and other

personal matters. As is true for any student, demands for self-regulation skyrocket upon entering

college, not only with respect to educational matters but also in terms of various personal and

social responsibilities. This developmental transition is indeed normative and often the reason

that beginning students experience trouble adjusting to college life. For students with ADHD,

however, this same developmental challenge is amplified many times over due to their inherent

deficit in self-regulation (Fleming & McMahon, 2012), and the fact that most, if not all, external

supports have been removed (Meaux, Green, & Broussard, 2009). Further complicating matters

is that many students do not fully understand or accept their ADHD, and therefore are reluctant

to seek campus support services that require disclosure of a condition that makes them different

from their peers.

Treatment of ADHD in College

While additional research is needed to identify the causal mechanisms responsible for

these outcomes, what remains clear is that college students with ADHD are at increased risk for

a broad range of functional impairments and that the severity of these impairments is of

sufficient clinical significance to warrant intervention. Somewhat surprisingly, very little

treatment research of this type has been conducted to date (DuPaul & Weyandt, 2009; Green &

Rabiner, 2012). The only medication study of which we are aware is one recently conducted by

DuPaul and his colleagues (2012), who utilized a double-blind, placebo-- controlled crossover

design to investigate the efficacy and safety of Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (LDX) among

college students with ADHD. Their findings led them to conclude that LDX was efficacious,

bringing about large reductions in ADHD symptoms and improvements in executive functioning,

along with smaller effects for psychosocial functioning. In terms of studies using nonmedication

approaches, improvements in educational functioning have been reported for college students

with ADHD following exposure to semester-long strategy instruction (e.g., organization, test

taking, note taking) delivered by graduate students in special education (Allsop, Minskoff &

Bolt, 2005). Of note, one of the factors thought to be related to successful outcome in this study

was the supportive nature of the strategy instructor–student relationship, which was derived from

qualitative analyses. Less compelling but positive outcome findings have also been reported in

studies that used coaching (Prevatt, Lampropoulos, Bowles, & Garrett, 2011) and assistive

reading software (Hecker, Burns, Elkind, Elkind, & Katz, 2002) to address the needs of college

students with ADHD.

A New Treatment Approach: ACCESS

To the best of our knowledge, no well-controlled study to date has investigated the

efficacy of psychological treatment of college students with ADHD. As a first step in addressing

this need, our team has been conducting an open clinical trial over the past two years with

college students who have ADHD. Our program, known as ACCESS (Accessing Campus

Connections and Empowering Student Success) is the student support piece of a larger project

known as College STAR (Supporting Transition, Access, and Retention), which is a three-year

foundation

1

-funded project awarded to the University of North Carolina system and currently

involving the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG), East Carolina University,

and Appalachian State University.

Over the past two years numerous refinements have been made to ACCESS, some of

which impacted its duration. For example, in its first semester of operation ACCESS began as a

six-week pilot program for the first six participants. In the two semesters that followed, a total of

31 participants received a 10-week version of this same program. It soon became apparent that

this 10-week program was very difficult to incorporate into a single 15-week semester, given the

need to recruit and screen participants during the first few weeks of the semester and then do

posttreatment measures at the end of the semester. Primarily for this reason ACCESS was

shortened to eight weeks for the other six participants included in this paper. ACCESS has

remained an eight-week program for the new participants enrolled this fall and will remain an

eight-week program for the duration of our three-year funding period. Generally speaking, the

topic content has remained the same regardless of how many sessions were delivered. Although

the 10-session program allowed for covering certain topics in greater detail, whatever benefits

may have resulted from this 10-session format were outweighed by the costs—in this case, the

impracticality of conducting all pretreatment, treatment, and posttreatment aspects of the

program within a single 15-week semester.

In its current and final form, ACCESS now includes an eight-week active treatment

protocol, followed by a maintenance phase in the subsequent semester. In the active treatment

phase participants meet weekly for 90 minutes of group cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and

also receive eight 30-minute individual mentoring sessions. During the maintenance phase,

participants participate in two booster CBT group sessions scheduled near the start and midpoint

of the semester, and receive five to six 30-minute individual mentoring sessions occurring every

two to three weeks.

Group Treatment

In the absence of existing psychosocial treatment studies with college students, we turned

to the adult ADHD treatment literature to help guide the creation of the ACCESS group

treatment protocol. In particular, we were influenced by the seminal empirical work of Safren

(Safren, Perlman, Sprich, & Otto, 2005) and Solanto (2011). Thus, evident in the group treatment

portion of our protocol are CBT elements common to both programs, which we have adapted for

use with college students and standardized in a treatment manual. This includes psychoeducation

and skills training to help students cope more effectively with the executive functioning deficits

inherent in ADHD, thereby increasing the likelihood for improving functioning across multiple

life domains. Specifically, ACCESS is designed to increase knowledge of ADHD and awareness

of campus resources; to improve organization, time management, and other behavioral skills; and

to teach cognitive therapy strategies for the purpose of increasing adaptive thinking that

promotes greater treatment adherence and reduced risk for secondary emotional and social

problems.

In contrast with the adult CBT interventions (Safren et al., 2005; Solanto, 2011) that

deliver their main treatment components primarily in a sequential fashion—that is, an ADHD

knowledge module followed by a behavioral skills module followed by a cognitive therapy

module— ACCESS delivers its main treatment components concurrently. More specifically, a

portion of each group treatment session addresses ADHD knowledge, behavioral skills, and

cognitive therapy.

The rationale for doing so was based in part on developmental considerations gleaned

primarily from clinical experience. For many college students, their understanding of ADHD is

limited, often based on what parents and teachers have told them. For still others, their

acceptance and ownership of ADHD is also limited, sometimes due to long-standing

developmentally appropriate resistance to whatever parents and other adults tell them; at other

times, due to a preference not to embrace a label that can have negative connotations, especially

as it relates to acceptance within a peer group. For developmental reasons such as these, along

with preliminary data from our ongoing projects, we concluded that the need for providing

psychoeducation about ADHD was much greater than that for older adults. Thus, we increased

the intensity of the ADHD psychoeducation in the CBT group protocol.

A major reason for simultaneously addressing all three major treatment components in

each CBT group session was to increase the variety of the material being presented in an effort to

maintain student interest and participation in the program. For some students, for example, there

is more need for the cognitive therapy piece than the behavioral piece, or vice versa. Rather than

require students to wait for what they need, potentially boring them and losing their interest

along the way, we opted to present all three treatment components together in each session.

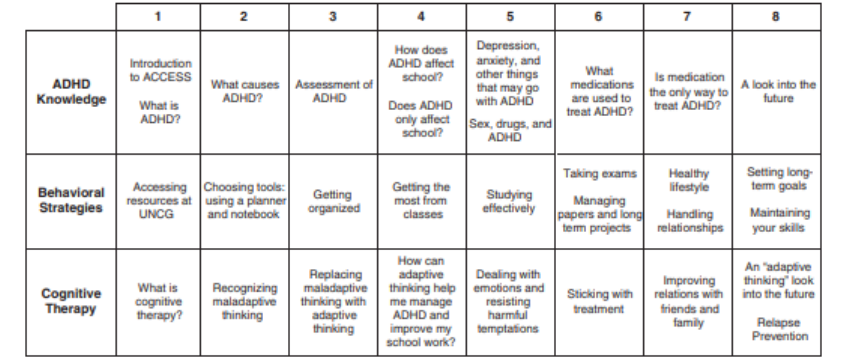

As can be seen in Figure 1, another distinctive feature of ACCESS is that delivery of its

three major components is tailored to be developmentally appropriate for college students.

Moreover, within most sessions the three major components are integrated to address the same or

very similar topics. Portions of several sessions are also set aside for guest speakers to provide

information and to answer questions about the campus support units (e.g., Office of Disabilities

Services [ODS], Counseling Center) they represent.

Figure 1. Session-by-Session Outline for Group Cognitive-Behavior Therapy Component of

ACCESS

Groups generally include three to seven students at multiple points in their undergraduate

education. This group composition encourages the more experienced students to share their

experiences and tips with the less experienced students. While keeping the personal information

discussed in group confidential is emphasized, students are encouraged to support one another

outside of the group (e.g., studying together, helping one another with transportation to the

group). All groups are led by licensed Ph.D.-level psychologists.

At the beginning of every session each group member receives detailed handouts

summarizing the major points of that session. Such handouts provide an additional sensory

modality for processing the session, as well as a template for organizing written notes. These

same handouts also serve to guide between-session practice and later can be used as a reminder

during the maintenance phase and beyond. Students are given a folder to store their handouts and

are encouraged to keep them for later reference.

Although some group content is presented in a lecture format, a back-and-forth, question-

and-answer presentation style is used whenever possible to encourage active student

participation. For example, when discussing how ADHD may affect students academically,

students are invited to share their own perspectives on how ADHD has influenced their academic

functioning. Invariably, stories told by one student spark an immediate “That happened to me

too” from other students who then share their war stories with one another, thereby contributing

to group cohesion. During the behavioral strategies portion of each session, the group leader

often opens the discussion by asking students what strategies are working well, or not so well.

When a participant reports not having success with a particular strategy, the group leader often

asks the other members of the group to give that participant direct feedback, emphasizing what

he or she can do to use a particular strategy more effectively. A common example of this type

of situation is when students show their planners to other group members, pointing out how their

adaptations of the system (e.g., use of different colored pens, blocking out study times in various

ways, stapling “to-do” lists directly into their planners) might also be of benefit to them. Similar

strategies are used during the cognitive therapy portion of treatment, during which a whiteboard

is used as a visual aid to guide students through thought exercises (e.g., completing thought

records challenging maladaptive thoughts).

In contrast with the CBT groups in the active phase of treatment, the two CBT group

sessions in the maintenance phase of treatment are substantially less structured in order to be

tailored to the needs of each participant. In particular, the two scheduled booster sessions provide

an opportunity for addressing new questions about ADHD that may have arisen, for

troubleshooting participants' implementation of behavioral strategies, and for refining participant

use of cognitive therapy strategies. Another important clinical benefit of these booster sessions is

that they provide an opportunity for group members to reconnect with one another and to receive

support from fellow group members.

Mentoring

Concurrent with their group work, students work individually with mentors to help them

apply what they have learned in group, connect with campus resources, and deal with daily life

issues. More specifically, mentors monitor student understanding of ADHD and help them apply

behavioral and adaptive thinking strategies to situations that may occur outside of group

treatment or perhaps are better suited to one-on-one rather than group discussions. As a way of

addressing academic performance and personal success, mentors also provide guidance on how

to access campus support units appropriate to student needs. In addition, mentors help students

develop realistic goals, monitor their follow-through on achieving those goals, and provide

students with ongoing support (Allsop et al., 2005) and personal coaching (Prevatt et al., 2011).

All mentors have a background in psychology, ranging in experience from graduate students in

nonclinical master’s degree programs to postdoctoral fellows in clinical psychology.

During the first session, which occurs during the first week of group CBT, mentors

review students' current academic and personal functioning, use of campus resources, challenges,

and goals for treatment. In subsequent sessions, which run concurrently with the remaining seven

weeks of group CBT, mentors perform a brief check-in with the participant, collaborate with the

participant to set an agenda, review homework from the previous session, review group

materials, set new goals and homework assignments, and cover other topics as needed and as

requested by participants. The time spent on each of these areas varies according to the needs

and interests of each student; applying the material presented in group that the mentor and

student feel would be most helpful is emphasized. In the final session, mentors discuss ways for

students to maintain their skills and performance once treatment ends.

During the maintenance phase, mentoring sessions are less numerous and even more

flexible, guided primarily by student needs and preferences. Thus, some students may choose to

use these sessions to review and refine their use of behavioral strategies, whereas others may opt

for using these sessions primarily for personal goal setting and support.

Method

Participants

Over the past two years a total of 43 undergraduate students from UNCG have formerly

participated in our open clinical trial with ACCESS. Participants were recruited from multiple

sources, including cases seen at a campus-based ADHD specialty clinic where CBT was one of

the recommendations made during a clinical evaluation feedback session (40%); referrals from

the Office of Disability Services (ODS) and other campus units (30%); freshmen who became

aware of the program during summer orientation sessions (19%); students referred by their

parents (5%); and students who learned of the program via word of mouth (6%). Participants

included 27 females and 16 males, encompassing first-- year students through seniors. Ages

ranged from 17 to 27; the mean age of participants is 20.3 years. In line with UNCG

demographics, 16% of the sample is Hispanic, and 21% come from African American and

multiracial backgrounds.

Ninety-five percent of the participants had been diagnosed with ADHD prior to entering

ACCESS; of these, only 53% had been formally diagnosed during childhood or adolescence.

ADHD status was further assessed to ensure that all participants met full DSM-IV criteria for

ADHD as determined either by a recently completed psychological evaluation or by a screening

completed by the ACCESS team. Multiple methods and multiple informants were used to make

this diagnostic determination, consistent with best-practice recommendations for diagnosing

ADHD in adults (Barkley et al., 2008). This included self-report and other report versions of the

ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD RS; DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulos, & Reid, 1998), modified to

address both childhood and current symptoms. Students also completed the Conners Adult

ADHD Rating Scale, Self-Report, Long Version (CAARS-S:L; Conners, Erhardt, & Sparrow,

2006), from which the CAARS-S:L DSM-IV Inattention and Hyperactivity–Impulsivity scores

were used to address the developmental deviance of ADHD symptoms. Together with these

rating scales, a semistructured, clinician-administered interview was conducted to confirm

ADHD status.

Based on student responses to probe questions during a review of background

information, selected modules from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID-

I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) were administered to evaluate for the presence of

both exclusionary and comorbid psychiatric conditions. Seventeen of the 43 students (40%) met

DSM-IV criteria for mood disorders, and 14 (33%) met DSM-IV criteria for an anxiety disorder.

Other comorbid diagnoses included adjustment disorders, substance abuse and dependence

disorders, and learning disorders. Overall, 25 of the 43 students (58%) had at least one comorbid

diagnosis. A majority of students (59%) reported that, at some point during college, they had

taken psychiatric medication, either for ADHD symptoms or for another disorder. Data also

indicated that 38% of students had utilized psychotherapy since starting college.

Given the high rates of comorbidity reported for adults with ADHD (80%; Barkley et al.,

2008), participants were included in ACCESS even if they had diagnosable depression and

anxiety disorders, which represent the majority of comorbid conditions that are likely to be

present. The comorbid presence of several other conditions, however, was exclusionary,

including autism spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder, and other psychiatric conditions whose

treatment precludes participation in the study. Whether or not they had comorbid diagnoses,

participants receiving pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and other types of support services were

allowed into the study, as one of the goals of ACCESS is to increase access to and utilization of

such treatment services.

Measures

Pretreatment data were collected during the two weeks prior to the start of the CBT

groups. Posttreatment data were collected at the end of the final group session. Posttreatment

measures were administered by members of the research team unaffiliated with the participants.

Whenever possible, pretreatment measures were also administered by members of the research

team unaffiliated with the participant; occasionally, the group leader administered pretreatment

measures due to schedule conflicts.

Clinical Change Mechanisms

The underlying assumption of the ACCESS program is that if intended changes occur

with respect to ADHD knowledge, behavioral strategies, and cognitive therapy skills, then

corresponding improvements should occur in the various domains of daily functioning. As a

check on these hypothesized mechanisms of clinical change, four measures have been

administered prior to and immediately following active treatment. The first of these is a 50-item

Test of ADHD Knowledge that we developed, which requires participants to read a stem

description and then respond with either “agree,” “disagree,” or “not sure.” To assess for changes

in use of organization, time management, and other behavioral strategies, we also developed the

Strategies for Success measure, which includes 30 items that students rate on a scale from 1 (not

well) to 5 (very well) regarding how well they perform various behaviors, such as “Using a

planning calendar” and “Setting long-term goals.” Two additional measures were developed to

assess ADHD-related cognitions. The first of these is the ADHD Cognitions Test (ACT), a rating

scale procedure that asks respondents to indicate on a 1 to 5 basis the degree to which they

engage in various ADHD-related cognitions, including items that represent maladaptive

cognitions (e.g., “I need it now,” “Being impulsive is a big part of who I am”), as well as items

that are reverse coded and represent adaptive thinking, such as “I’m careful in making

decisions.” Also developed and implemented as a measure of cognitions was the Cognitive

Response Test for ADHD (CRT-A), which requires respondents to complete sentence stems that

trigger maladaptive thinking responses among college students with ADHD (e.g., “Our professor

gives back our tests and my grade is one of the lowest in the class. I think to myself . . ”; “One of

my friends tells me that he or she will call me back in a few minutes but never does. I think to

myself . . .”). All responses were coded by multiple raters for reliability and given scores of 0 if

they showed no maladaptive thinking patterns, 1 if they showed a maladaptive thinking pattern

that the participant then corrected (e.g., an overgeneralization followed by a retraction of that

statement), or 2 if they showed a maladaptive thinking pattern and no sign that the pattern was

corrected.

Functional Outcome Measures

The CAARS-S:L DSM-IV inattentive symptoms, DSM-IV hyperactive–impulsive

symptoms, and DSM-IV ADHD symptoms total scores were used to assess treatment-induced

changes in primary ADHD symptoms. Working memory and other aspects of executive

functioning were assessed using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Adult

Version (BRIEF-A; Gioia, Isquith, Guy, & Kenworthy, 2000). The BRIEF-A is a self-report

instrument that takes approximately 10 minutes to complete and has adequate psychometric

properties. The BRIEF-A generates three general composite scores—Behavior Regulation Index,

Metacognition Index, and General Executive Composite—all of which served as outcome

variables. Participants also completed dimensional measures of psychological functioning,

including the Beck Depression Inventory–II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), and the Beck

Anxiety Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1993). Both of these measures have sound psychometric

properties and were used to monitor treatment-induced changes in psychological functioning. As

noted above, one of the goals of ACCESS is to increase participants’ awareness and use of

campus supports and other resources. Thus, students provided responses to service use

questionnaires to determine whether this type of change had taken place. Archival educational

data were also collected, including GPA for each semester, the proportion of course credits

attempted and earned, the number of course withdrawals and incomplete courses, leaves of

absence, and academic probations and suspensions.

Preliminary Findings

Attrition

Only three out of these 43 participants completely dropped out of treatment. Such a low

rate of attrition is in large part due to the high degree of satisfaction with the program, with

100% of the participants who completed posttreatment interviews (N = 30) stating that they

would recommend ACCESS to other students with ADHD. This same level of satisfaction

presumably contributed to the large number of sessions that were attended. Using an 80%

attendance threshold, 86% of our participants finished the CBT group treatment and 84%

completed the mentoring portion. Some participants who were partial completers or who

dropped out of treatment were nonetheless willing to complete posttreatment outcome measures,

and therefore a higher rate of posttreatment data completion (93%) was possible. During the

follow-up semester, 68% of participants attended at least one booster session and 82% met with

their mentor at least once. Full utilization of the program was less common; only 54% attended

both booster sessions and only 54% met with their mentor for five or more sessions.

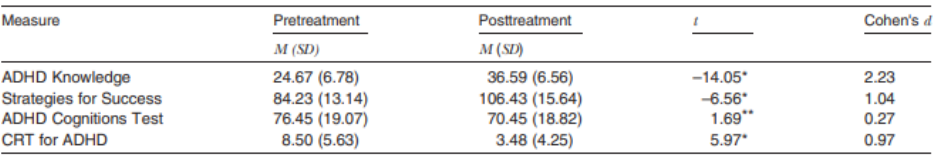

Table 1 Summary of Measures Assessing Clinical Change Mechanisms

Note. ADHD Knowledge = Test of ADHD Knowledge; CRT for ADHD = Cognitive Response

Test for ADHD.

* p ≤ .001; ⁎⁎ p < .10.

Treatment Fidelity

Treatment manuals with detailed session-by-session outlines were developed to guide the

group CBT leaders and mentors in their delivery of the ACCESS program. All CBT group

sessions were video recorded but it was not possible to do so for the mentoring sessions due to

space and equipment limitations. A random sampling and review of the CBT group sessions

revealed excellent adherence to treatment, operationalized in terms of the number of content

items in each session outline that were covered. All reviewed sessions exceeded the 90%

threshold that was used to classify treatment delivery as satisfactory.

Clinical Change Mechanisms

Preliminary two-tailed paired t test analyses of the pretreatment to posttreatment data

revealed significant improvements in all three hypothesized mechanisms of change. This

includes increased knowledge of ADHD, increased use of organizational and other behavioral

strategies, and reduced levels of maladaptive thinking on the CRT-A, all of which were highly

significant (p < .001) and associated with large to very large effect sizes (see Table 1).

Functional Outcome Measures

As shown in Table 2, paired t test analyses revealed significantly reduced levels of

inattentive symptoms (p < .001) and the ADHD symptom total (p < .001), as well as a trend

toward lower levels of hyperactive–impulsive symptoms (p = .054). The effect sizes associated

with these improvements in inattentive symptoms and the ADHD symptom total fell within the

moderate to large range, whereas there was only a small effect found for the changes in

hyperactivity–impulsivity. Significant improvements (p < .001) were also found for the three

domains of executive functioning measured by the BRIEF-A, all of which represented large

effects. Although not statistically significant, trends were detected with respect to reductions

in levels of anxiety (p = .055) and depression (p = .134), for which the effect sizes were small.

The degree to which the above significant findings

represent normalization of functioning was also addressed via examination of scores falling

above and below a 1.5 standard deviation cut point at pretreatment versus posttreatment. For the

ADHD symptom total, the percentage of participants within 1 standard deviation of the mean

increased from 18% at pretreatment to 40% at posttreatment. This change in overall self-reported

ADHD symptoms was driven primarily by the increase in Inattentive scores (8% vs. 28%) and to

a lesser extent by changes in the Hyperactive–Impulsive scores (53% vs. 68%). For the BRIEF-A

Global Executive Composite, the percentage of participants within 1 standard deviation of the

mean increased from 10% at pretreatment to 50% at posttreatment. Increases were also evident

for the Metacognition Index (8% vs. 45%) and the Behavioral Regulation Index (45% vs. 65%).

Mixed findings emerged from preliminary analyses of the archival educational data,

which in part may be due to the fact that no pretreatment data were available for freshmen and

therefore the sample size was reduced. For those for whom complete educational data were

available (N = 23), there was a statistically nonsignificant change in GPA, increasing from 2.3 in

the semester immediately preceding treatment to 2.5 at the end of the semester in which

treatment was provided. A different picture emerged when examining these same educational

data categorically, defined in terms of the university’s cut point for academic probation (i.e.,

GPA below 2.0). More specifically, fewer participants fell into the academic probation range in

the semester in which treatment was provided (18.9%) versus the semester immediately prior

to treatment (26.1%).

Student responses to questionnaires (N = 37) also suggested increased utilization of

campus services. Most striking was the increase in the use of the ODS. Although 41% of

participants were registered with ODS at pretreatment, only 19% had actually met with ODS

staff to develop a list of academic accommodations. At posttreatment, 62% of participants had

chosen to register and 57% of participants were using accommodations. In addition, five students

who had not used medication to treat their ADHD symptoms during college were using

medication by posttreatment and one student who had not sought psychotherapy during college

had begun psychotherapy treatment. Six students who had never used tutoring reported using

tutoring services by the end of the program and seven students who had never used the campus

Writing Center reported that they had used this service at least once.

Case Example

Although the above preliminary findings are encouraging, it is important to keep in mind

that these results emanate from group-based statistical analyses and descriptions. Not included in

such reporting is a detailed analysis of the clinical significance of the findings, that is, the

meaning of the results as they relate to student functioning at an individual level. A formal

examination of clinical significance is beyond the scope of this paper; however, as a way of

capturing how ACCESS might impact a college student with ADHD, the following case example

is presented. Important to note is that all identifying data have been removed from this example;

where necessary, some descriptions have been modified slightly to further protect the identity of

the individual.

“Kimberly” entered the ACCESS program as a junior. She was diagnosed with ADHD

during her elementary school years and had taken medication to treat her ADHD symptoms since

that time. She reported some difficulty in the past with anxiety but only met criteria for ADHD,

combined type, at the time of screening. When she started ACCESS, she was already using some

campus resources; she had registered with ODS and had investigated the possibility of tutoring

as well. She expressed enthusiasm about the opportunity to take part in ACCESS.

Kimberly participated actively in the CBT group sessions, attending all but one session.

As a more senior student than some of her fellow group members, she seemed to enjoy sharing

her tips and experiences with the other students. She made at least one friend in the group who

she saw socially outside of the program. In discussions covering knowledge of ADHD, Kimberly

openly shared her experiences. Kimberly was consistently cooperative when new behavioral

strategies were suggested, and she reported trying a number of new strategies for improving her

time management and academic performance. However, she sometimes seemed resistant to

trying new techniques. For example, when discussing strategies for completing papers, she noted

that procrastination had “worked” for her in the past, so it was difficult to encourage her to

change that habit. Kimberly was already using a planner to some extent at the start of the

program, but she was not yet taking full advantage of it. She was not using the planner to break

down tasks into manageable steps or to schedule study sessions; she improved on both of these

skills during the program. During the CBT portion of the groups, Kimberly was easily able to

provide examples of maladaptive thinking. She was skilled at developing alternate, more realistic

thoughts, whether when working her own thought records or when helping a group member

challenge maladaptive thoughts.

Kimberly attended all of her mentoring appointments. She was very motivated and easily

set short- and long-term goals for herself. At the start of the program, she expressed the idea that

her negative study habits could “never” be changed. During the course of the program she

developed more effective study strategies, learned to stick to a study schedule, and learned better

note-taking procedures and test-taking strategies. In addition, she developed better time

awareness with respect to both academics and social life and improved in her use of to-do lists

and in setting reminder alarms. In addition, she developed better awareness of how her thought

patterns affected her social relationships. Kimberly utilized academic accommodations through

the ODS and participated in campus tutoring as well. Academically, her grades improved; her

GPA during her semester of treatment was nearly a full grade point higher than her GPA from

the previous semester.

During the follow-up semester, Kimberly attended both booster sessions and five

mentoring sessions. She continued to have a strong relationship with her mentor and was eager to

meet with her. She stated that her transition to the new semester was easier than usual because

she was continuing to use the strategies she had learned from the program. She has made

considerable progress and views the program as a valuable support.

Discussion

The impaired functioning of college students with ADHD has critical implications for the

long-term financial and mental health status of this population, as well as for institutions of

higher learning concerned with graduation and retention rates, and for society as a whole.

Despite the obvious need for intervention, very little treatment research has been

conducted with this population to date (DuPaul & Weyandt, 2009; Green & Rabiner, 2012).

Although a well-controlled medication trial study recently has been published (DuPaul et al.,

2012), missing from the literature are studies investigating the efficacy of psychosocial

treatment. In response to this situation, our team has been developing and testing ACCESS, a

psychosocial treatment program for college students with ADHD.

Guided by conceptual considerations and empirical findings, ACCESS includes elements

of previously reported treatment protocols (Allsop et al., 2005; Prevatt et al., 2011; Safren et al.,

2005; Solanto, 2011) that have been blended together to create a developmentally appropriate

intervention that uses a unique combination of group CBT and individual mentoring to meet the

broad educational, psychological, social, and executive functioning needs of the ADHD college

population. Preliminary findings from this ongoing project are most encouraging. Attesting to the

construct validity of the design, there were clear improvements in the hypothesized mechanisms

of clinical change (i.e., ADHD knowledge, behavioral strategies, adaptive thinking), representing

large to very large effects. Medium to large effects were also associated with the significant

improvements observed in self-reported ADHD symptoms and executive functioning. Trends

approaching statistical significance further suggested that ACCESS may contribute to

improvements in emotional functioning. Also emerging from the data was preliminary evidence

of real-world educational benefits, along with increased utilization of campus resources.

This latter finding regarding campus resources warrants additional comment. ACCESS is

not intended to be a stand-alone intervention that addresses all of the challenges facing college

students with ADHD. On the contrary, ACCESS is designed to empower students with the

knowledge and skills necessary to better manage their ADHD and any comorbid conditions that

may be present, in part through the assistance it gives students in making connections with other

campus units that provide clinical services and other support. In this regard, ACCESS is best

viewed as an integral component of an overall multimodal treatment approach that includes other

interventions (e.g., medication management, counseling, tutoring).

Although promising, such findings are limited by the fact that ACCESS has thus far been

delivered in an open clinical trial. Future research must therefore include a control or comparison

group to determine whether these preliminary outcomes are in fact due to ACCESS versus

resulting from nonspecific therapeutic attention factors, the effects of repeated testing, and so on.

Another factor limiting any interpretation of these preliminary findings is the restricted range of

outcomes used in the design. To address this limitation, future research will need to

consider broadening the scope of outcomes in a way that includes not only multiple domains of

daily functioning but also less reliance on self-report. Because we have only analyzed a limited

amount of data from student records, we are not in a position to comment on the full impact of

ACCESS on educational functioning. Any statements on the stability of ACCESS-induced

improvements over time must also await our upcoming analyses of data collected from the

maintenance phase of our project.

Another unexplored area of great clinical interest is the degree to which a student’s level

of motivation and other individual differences predict successful outcome. Although most

students were actively engaged in ACCESS, some were not. Often, those not appropriately

engaged were freshmen whose parents had encouraged them to participate during their first

semester on campus. For others, dealing with comorbid depression or anxiety seemed to interfere

with their participation. For still others, holding down a job while attending school often led to

scheduling conflicts that made treatment adherence difficult. To determine for whom ACCESS is

best suited, it is critical that future research examine these and other individual differences.

To the extent that future research supports the preliminary findings from this study,

ACCESS can potentially serve as a model intervention for use on many college campuses. The

eight-week format that we now use for ACCESS would likely accommodate any variability in

the length of semesters, especially those ranging from 12 to 16 weeks. Such may not be the case,

however, for institutions using a quarterly rather than a semester system. There is also some

degree of flexibility in the setting in which ACCESS may be delivered. Given that most colleges

and universities have student counseling centers, this type of campus setting would seem

especially well suited to offering an ACCESS program. So too would an ODS, which is also

found on most campuses. Even more important than the convenience of the physical setting,

however, is the training and experience level of the staff housed within those settings. At a

minimum, successful implementation of ACCESS requires background and expertise in the use

of cognitive and behavioral therapy strategies. Advanced evidence-based knowledge of ADHD

as a disorder is also considered to be an important prerequisite for professionals delivering

ACCESS. Thus, campus staff that have these qualifications would likely be in a position to

deliver ACCESS effectively. Such an assumption, however, is yet untested and therefore will

need to be substantiated by future research.

In conclusion, ACCESS is a promising new psychosocial program that has great potential

for being used in many different college and university settings. Of even greater importance are

its potential public health benefits, in that ACCESS can serve as a protective factor that increases

the likelihood that students with ADHD can be more successful not only during college but also

as they begin their developmental transition into the postcollege adult world.

References

Allsop, D. H., Minskoff, E. H. & Bolt, L. (2005). Individualized course-specific strategy

instruction for college students with learning disabilities and ADHD: Lessons learned

from a model demonstration project. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 20,

103–118.

Barkley, R. A. (2006). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and

treatment (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Barkley, R. A., Murphy, K. R., DuPaul, G. J., & Bush, T. (2002). Driving in young adults with

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Knowledge, performance, adverse outcomes, and

the role of executive functioning. Journal of the International Neuropsychological

Society, 8, 655–672.

Barkley, R. A., Murphy, K. R., & Fischer, M. (2008). ADHD in adults: What the science says.

New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Beck, A., & Steer, T. (1993). Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Education.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory–II. San Antonio,

TX: Psychological Corporation.

Conners, C. K., Erhardt, D., & Sparrow, E. (2006). Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales. Multi-

Health Systems.

DuPaul, G. J., Power, T. J., Anastopoulos, A. D., & Reid, R. (1998). Manual for the ADHD

Rating Scale–IV. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

DuPaul, G. J., Schaughency, E. A., Weyandt, L. L., Tripp, G., Kiesner, J., Ota, K., & Stanish, H.

(2001). Self-report of ADHD symptoms in university students: Cross-gender and cross-

national prevalence. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34, 370–379.

DuPaul, G. J., & Weyandt, L. L. (2009). College students with ADHD: Current status and future

directions. Journal of Attention Disorders, 13, 234–250.

DuPaul, G. J., Weyandt, L. L., Rossi, J. S., Vilardo, B. A., O'Dell, S. M., Carson, K. M., . . .

Swentosky, A. (2012). Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of the efficacy

and safety of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in college students with ADHD. Journal of

Attention Disorders, 16, 202–220.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (1996). Structured Clinical

Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC:

American Psychiatric Press.

Fleming, A. P., & McMahon, R. J. (2012). Developmental context and treatment principles for

ADHD among college students. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 303–

329.

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S., & Kenworthy, L. (2000). BRIEF: Behavior Rating

Inventory of Executive Function professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological

Assessment Resources.

Glutting, J. J., Youngstrom, E. A., & Watkins, M. W. (2005). ADHD and college students:

Exploratory and confirmatory factor structures with student and parent data.

Psychological Assessment, 17, 44–55.

Green, A. L., & Rabiner, D. L. (2012). What do we really know about college students with

ADHD? Neurotherapeutics, 9, 559–568.

Grenwald-Mayes, G. (2002). Relationship between current quality of life and family of origin

dynamics for college students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of

Attention Disorders, 5, 211–222.

Hecker, L., Burns, L., Elkind, J., Elkind, K., & Katz, L. (2002). Benefits of assistive reading

software for students with attention disorders. Annals of Dyslexia, 52, 243–272.

Heiligenstein, E., Guenther, G., Levy, A., Savino, F., & Fulwiler, J. (1999). Psychological and

academic functioning in college students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Journal of American College Health, 47, 181–185.

Heiligenstein, E., & Keeling, R. P. (1995). Presentation of unrecognized attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder in college students. Journal of American College Health, 43, 226–

228.

Kollins, S. H. (2008). ADHD, substance use disorders, and psychostimulant treatment: Current

literature and treatment guidelines. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 115–125.

Mannuzza, S., Gittelman-Klein, R., Bessler, A., Malloy, P., & LaPadula, M. (1993). Adult

outcome of hyperactive boys: Educational achievement, occupational rank, and

psychiatric status. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50, 565–576.

McKee, T. E. (2008). Comparison of a norm-based versus criterion-- based approach to

measuring ADHD symptomtology in college students. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11,

677–688.

Meaux, J. B., Green, A., & Broussard, L. (2009). ADHD in the college student: A block in the

road. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16, 248–256.

Norvilitis, J. M., Ingersoll, T., Zhang, J., & Jia, S. (2008). Self-reported symptoms of ADHD

among college students in China and the United States. Journal of Attention Disorders,

11, 558–567.

Norwalk, K., Norvilitis, J. M., & MacLean, M. G. (2008). ADHD symptomatology and its

relationship to factors associated with college adjustment. Journal of Attention Disorders,

1–8.

Prevatt, F., Lampropoulos, G. K., Bowles, V., & Garrett, L. (2011). The use of between session

assignments in ADHD coaching with college students. Journal of Attention Disorders,

15, 18–27.

Pryor, J. H., Hurtado, S., DeAngelo, L., Blake, L. P., & Tran, S. (2010). The American

freshman: National norms fall 2010. Los Angeles, CA: Higher Education Research

Institute, University of California, Los Angeles.

Rabiner, D. L., Anastopoulos, A. D., Costello, J., Hoyle, R. H., & Swartzwelder, H. S. (2008).

Adjustment to college in students with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11, 689–

699.

Reaser, A., Prevatt, F., Petscher, Y., & Proctor, B. (2007). The learning and study strategies of

college students with ADHD. Psychology in the Schools, 44, 627–638.

Richards, T. L., Deffenbacher, J. L., & Rosén, L. A. (2002). Driving anger and other driving-

related behaviors in high and low ADHD symptom college students. Journal of Attention

Disorders, 6, 25–38.

Safren, S. A., Perlman, C. A., Sprich, S., & Otto, W. (2005). Mastering your adult ADHD: A

cognitive-behavioral treatment program therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford

University Press.

Shaw-Zirt, B., Popali-Lehane, L., Chaplin, W., & Bergman, A. (2005). Adjustment, social skills,

and self-esteem in college students with symptoms of ADHD. Journal of Attention

Disorders, 8, 109–120.

Solanto, M. V. (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD: Targeting executive

dysfunction. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Upadhyaya, H. P., Rose, K., Wang, W., O’Rourke, K., Sullivan, B., Deas, D., & Brady, K. T.

(2005). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, medication treatment, and substance use

patterns among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent

Psychopharmacology, 15, 799–809.

Weyandt, L. L., Iwaszuk, W., Fulton, K., Ollerton, M., Beatty, N., Fouts, H., . . . Greenlaw, C.

(2003). The internal restlessness scale: Performance of college students with and without

ADHD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 36, 382–389.

Wolf, L. E. (2001). College students with ADHD and other hidden disabilities: Outcomes and

interventions. In J. Wasserstein, L. E. Wolf, & F. F. LeFever (Eds.), Adult attention

deficit disorder: Brain mechanisms and life outcomes (pp. 385–395). New York, NY:

New York Academy of Sciences.