The Voice of the Child in Family Law:

Exploring Strategies, Challenges, and

Best Practices for Canada

Michael Saini, PhD, MSW, RSW

Pathways to co-parenting

March 31, 2019

The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views

of the Department of Justice Canada or the Government of Canada

2

Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by

any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission,

unless otherwise specified.

• You are asked to:

- exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced;

- indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author

organization; and

- indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the

Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation

with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada.

• Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from

the Department of Justice Canada. For more information, please contact the Department of

Justice Canada at: www.justice.gc.ca

©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Justice and Attorney

General of Canada, 2019

The Voice of the Child in Family Law: Exploring Strategies, Challenges, and Best Practices

for Canada.

J4-132/2023E-PDF

978-0-660-46652-1

3

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................................................................. 4

Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................................ 5

Chapter 1: Introduction and Objectives of the Project........................................................................................................ 7

Chapter 2: A Brief History of Children’s Voices in Canada .............................................................................................. 8

Chapter 3: Brief Review of Children’s Experiences of Providing Voice ..........................................................................13

Children’s Input into Parenting Plans ............................................................................................................................13

Reasons why Children want their Voices Heard ...........................................................................................................14

Children’s Capacity in Decision-Making ......................................................................................................................15

Effects of Children’s Participation ................................................................................................................................15

Children’s Advice ..........................................................................................................................................................16

Summary .......................................................................................................................................................................16

Chapter 4: Methods for Including Children’s Voices in Family Law Matters ..................................................................17

Non-Court Child Inclusive Methods .............................................................................................................................17

Children Talking with Parents ..................................................................................................................................18

Children Sharing their Views with Professionals ......................................................................................................19

Child-Inclusive Mediation .........................................................................................................................................20

Court Based Child-Inclusive Methods ...........................................................................................................................21

Child-Inclusive Conferencing ....................................................................................................................................21

Appointment of Children’s Lawyer ............................................................................................................................22

Children Interviews of Children within Parenting Plan Assessments .......................................................................23

Voice of the Child Reports .........................................................................................................................................25

Child-Inclusive Collaborative Law............................................................................................................................26

Judicial interviews with children ...............................................................................................................................27

Children’s testimony in court (children as witnesses) ...............................................................................................30

Post-Court Order for Opportunities to Hear Children’s Voices ....................................................................................31

Child-Inclusive Parenting Coordination ...................................................................................................................31

Children’s Voices in Supervised Access Services ......................................................................................................32

Summary of Methods ....................................................................................................................................................33

Chapter 5: Prevalence of child-inclusive methods in family law ......................................................................................34

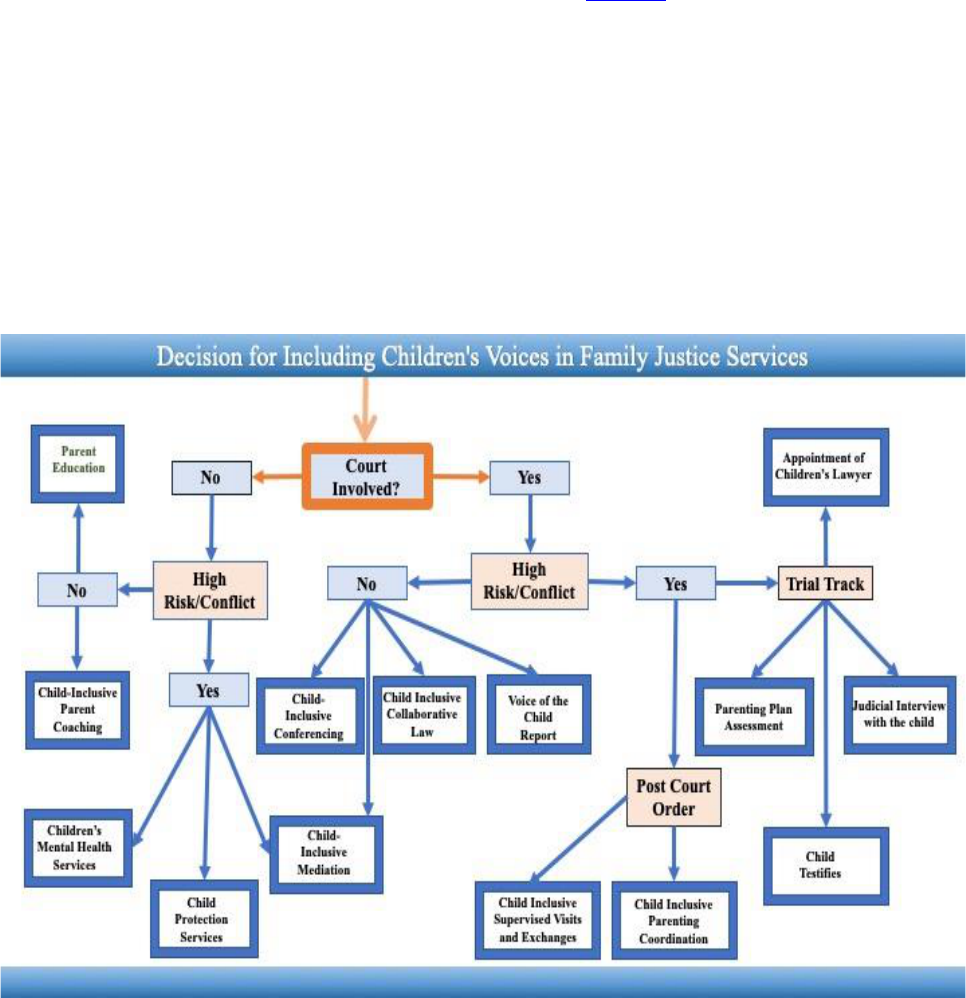

Chapter 6: Decisions for including child-inclusive methods .............................................................................................35

Figure 1: Decision tree for choosing method for child inclusion ......................................................................................36

Summary ...........................................................................................................................................................................38

Chapter 7: Discussion and Implications ............................................................................................................................39

Enhancing a Child-Centric Family Justice System ........................................................................................................40

Practice considerations ..................................................................................................................................................41

Considerations for Parents Hearing Children’s Voices .................................................................................................41

Future Research .............................................................................................................................................................42

Appendix A – Methodology ..............................................................................................................................................43

4

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the generous research assistance of Lily Chapnik Rosenthal, a graduate

student in the combined social work and law program at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work

and the Faculty of Law at the University of Toronto, who was instrumental during the information

retrieval process, the appraisal of the included studies and the legal case analysis.

This project could not have been possible without the financial support of the Department of Justice

Canada. I am indebted to the representatives from Family, Children and Youth Section (FCY) and

the Research and Statistics Division (RSD) at the Department of Justice Canada.

5

Executive Summary

Objectives of the Project

The objective of this project is to collect and collate research, describe existing methods to include

the children’s voices in family law in Canada (and internationally where relevant), to identify themes,

and to develop a comprehensive and accessible literature review. This review provides descriptions

of promising practices applicable to various aspects of the voice of the child and discussions of case

law.

Background

There is a heightened awareness that children’s views and preferences must be taken into

consideration when making decisions regarding their living arrangements. Article 12 of the United

Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, a treaty that Canada has signed and ratified,

specifies that children capable of forming their own views have the right to express those views

freely in all matters affecting them and that the child’s voice should be given due weight according

to the child’s age and maturity. The Convention does not, however, specify how children’s voices

should be heard. There remains debate in the literature about the strengths and limitations of the

various approaches that have emerged for facilitating children’s voices within family justice

services.

Key Findings

There is now recognition in both Canadian legislation and case law of the importance and value of

children’s participation in family justice procedures. Family legislation in almost all Canadian

jurisdictions now explicitly provides that the views of children must be considered as a factor in

making decisions based on their “best interests”, frequently with a proviso, such as “where these

views can reasonably be ascertained” or considering the age and maturity of the child.

To meet the need for hearing children’s voices in the context of separation, there has been a

growing emphasis on court-based services (Voice of the Child Reports, custody assessments, child-

inclusive parenting coordination, judicial interviewing) to provide children and youth with the

opportunity to provide their views about parenting plan considerations to complement the views of

their parents in the context of child custody disputes.

Less attention has been paid to providing children the opportunity to share their views about

parenting plan issues outside of the court context. This is especially concerning given that the

majority of parenting disputes will be resolved without ever going to trial, thus leaving many

children without adequate alternatives to share their views about decisions made regarding

parenting time post-separation.

Given that, for some children, there may be a risk associated with speaking to their parents about

their views and preferences, children need to be safeguarded from potential strain caused by their

parents’ inability or unwillingness to listen to their children.

6

Parent education programs and support groups can teach skills that help parents learn to listen to

their children and to talk with their children about their experiences of the separation process and

how parenting plan issues may affect their daily lives.

Children may report their views and preferences to their teachers, which may place the teachers in

the family law dispute as third-party collateral sources of children’s views. There has been a lack of

attention to the role of the teacher and further attention is needed to help teachers support children’s

voices when they are shared within the school setting.

When there is ongoing conflict between parents, children should be given the opportunity to speak

with a mental health professional. These professionals can listen to children outside of the court

process to provide children with the opportunity to talk about their views on their parents’

separation, their views about parenting options and any frustrations they may be experiencing due to

being caught in their parents’ dispute.

For the majority of families, parenting plan issues will be resolved without necessarily going to

court. For families involved in the courts, specialized methods for child inclusion and legislative

support for these programs have been established. It is important to consider children’s unique

needs and situation to determine which method may work best for a particular child to share their

experiences.

In situations of court involvement with lower levels of parental conflict and little risk of the child

developing loyalty conflicts with their parents, it may be useful for parents to use mediation offered

to them at entry into the courts. Mediation can quickly and efficiently create a parenting plan that

meets the needs of their children. Child-inclusive mediation approaches (e.g., interviewing children

about parenting plan issues and then integrating these views into the mediation with the parents) can

enhance children’s voices and provide opportunities for children’s participation process.

A Voice of the Child Report allows children to have their views and perspectives shared in family

disputes without necessarily requiring involvement of a lawyer or a full assessment by a mental

health professional. Voice of the Child Reports may provide a low-cost method for children to share

their experiences and provide input into parenting plan issues.

In higher-risk situations, such as cases involving child abuse, intimate partner violence, or

alienation, a parenting plan assessment may be the preferred approach for considering children’s

views. Parenting plan assessments typically entail a systematic and comprehensive consideration of

the various factors and issues involved in the dispute.

Judicial interviewing may be best reserved for cases moving towards trial preparation. The judge is

given the opportunity to speak with the child to understand from the child’s point of view and to

have a better understanding of the factors of the case to determine whether and when a trial should

proceed.

Implications

The extent to which children’s voices can be heard will depend on the services available to elicit

information and the adults and professionals’ ability to facilitate children’s input in post-separation

decision making.

7

There is no “best way” to hear from children during the family justice process. Several methods

have been developed to facilitate children providing their voices in the context of family law, but

many of these methods seem underutilized. For example, child-inclusive mediation and independent

legal representation for children are available in only a small portion of the high-conflict cases in

the courts.

It is clear from children’s reports that they want their voices included in decisions that affect them.

Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Children also supports hearing

children’s voices in all decisions that affect them. Based on the research, there needs to be increased

opportunities to hear children’s voices in family justice processes and a substantial investment to

support children’s access to these services, regardless of geographical location, culture and

language.

Another way to support hearing children’s views is to develop innovative services and approaches

outside of the court system to hear children’s voices. It seems counterproductive to give children the

opportunity to have input into the parenting plan only if the parents are unable to resolve these

issues and therefore turn to the courts to assist in these matters. To maximize children’s voices, the

family justice field needs to consider innovative ways to hear children’s voices outside of the court

process.

Chapter 1: Introduction and Objectives of the Project

Children can often be at the heart of parenting disputes, leaving parents, decision-makers, lawyers,

social workers, researchers, policy professionals and other practitioners asking important questions

about how to best ascertain the views of children. While the voice of the child can be defined in

different ways, it generally involves direct and indirect opportunities for children to have input into

decisions regarding parenting plans post-separation and the mechanics of making the wishes of

children known during parenting disputes, divorce or separation.

The increased focus on children's views in family law matters has led to important academic and

policy conversations regarding the optimal strategies and opportunities for including children’s points

of view when creating parenting plans post-separation and divorce. The Department of Justice Canada

has been actively considering children’s voices in family law matters and has spearheaded a number

of important projects regarding the methods for including children’s voices. This work includes a

collection of reports produced between 2002 and 2012 on the voice of the child in family law.

1

These

reports explain the rationale for hearing the voice of the child in family law matters, the domestic and

international legal background on the voice of the child, the historical debates in voice of the child

scholarship and the role of counsel for children. Current research on the voice of the child has shifted

1

Lorne D. Bertrand, Joanne J. Paetsch, Joseph P. Hornick & Nicholas Bala, “A Profile of Legal Aid Services in Family

Law Matters in Canada” (2002) Ottawa, ON: Department of Justice Canada; Ronda Besner, “The Voice of the Child in

Divorce, Custody and Access Proceedings” (2002) Ottawa, ON: Department of Justice Canada; Pauline O’Connor,

“Voice and Support: Programs for Children Experiencing Parental Separation and Divorce” (2004) Ottawa, ON:

Department of Justice Canada; Rachel Birnbaum, “Divorce and The Voice of the Child in Separation/Divorce

Mediation and other Alternative Dispute Resolution Processes” (2009) Ottawa, ON: Department of Justice Canada.

8

from questions about why the voice of the child is important to how to include the voice of the child.

Scholars have also noted that children want their voices heard without the constraints of social and

legal obstacles.

2

Given the opportunity, children generally appreciate the opportunity to share their

views.

3

There remains considerable debate about the key strategies to hear the voices of children in family

law matters. Several methods have been developed to hear children’s voices both within the context

of court services (e.g., judicial interviewing) and outside of the court process (e.g., child-inclusive

mediation). Children are also typically interviewed as part of child custody assessments performed

by social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists. Voice of the Child Reports provide children

with the opportunity to share their experiences, views and preferences regarding parenting plans.

Children can also share their views with lawyers who in turn share these views with the court. In

cases where family disputes are moving towards a trial, children may have the opportunity to meet

with the judge.

This project explores the different ways that the voice of the child can be considered in Canada and

the various approaches to include children’s voices within the context of Canadian family law (e.g.,

parenting plan assessments, Voice of the Child Reports, legal representation of a child, and judicial

interviews of children).

4

Further, this review provides descriptions of promising practices for bringing the voice of the child

into decision-making processes and discussions of case law where relevant. This report presents the

best available research and legal analysis regarding children’s voices and updates the picture of how

to incorporate children’s voices in family law situations in Canada. The review of research and law

serve to inform policy makers, family law practitioners, parents and the public. The promising

practices and discussion of advantages/disadvantages address the cultural changes of family law

that are needed to better address children’s voices within current practices.

Chapter 2: A Brief History of Children’s Voices in Canada

Historically, children in Canada have not had the opportunity to participate in decisions of custody

and access.

5

Until the last few decades, children were viewed as lacking the capacity to participate

in family law matters, as needing protection from parental conflict

6

or from being put in the middle

2

Rachel Birnbaum & Michael Saini, “A qualitative synthesis of children's participation in custody disputes” (2012) 22:4

Res. Soc. Work Pract. at 400.

3

Rachel Birnbaum & Nicholas Bala, “Views of the Child Reports: The Ontario Pilot Project” (2017) 31:3 Int J Law

Policy Family, at 344.

4

Supra note 2.

5

H.T.G. Andrews & Pasquale Gelsomino, “The Legal Representation of Children in Custody and Protection

Proceedings: A Comparative View” in Rosalie Abella and Claire L. Heureux-Dube eds., Family Law: Dimensions of

Justice (Toronto: Butterworths, 1983) 241; Ronda Bessner, The Voice of the Child in Divorce, Custody and Access

Proceedings. Department of Justice, Canada, 2002-FCY-1E (Ottawa, 2002) Online: dsp-

psd.communication.gc.ca/Collection/J3-1-2002-1E.pdf at 2, citing C. Bernard, R. Ward, & B. Knoppers, “Best Interests

of the Child Exposed: A Portrait of Quebec Custody and Protection Law” (1992-93), 11 Can. J. Fam. L. 57 at 136.

6

Anne Graham & Robyn Fitzgerald, “Taking Account of the “To and Fro” of Children’s Experiences in Family Law”

(2006) 31:2 Children Australia at 30; Virginia Morrow & Martin Richards, “The Ethics of Social Research with

9

of their parents’ disputes.

7

It was assumed that if children could be insulated from post-separation

decision-making, they would be sheltered from the turmoil of their parents’ relationship

breakdown.

8

Another assumption was that parents know what is in their child’s best interests

9

and,

hence, that adults adequately represent children’s views.

10

Legal and mental health authorities characterize this debate as one between the “rights” and

“protection” of children. For example, some child advocates favouring the protection of children

have typically viewed childhood as a special time, associated with an inability to make significant

decisions and dependency on parents or other care providers. Children's rights advocates, in

contrast, have focused on the child’s self-determination and equal treatment regardless of age.

In more recent years, some academics, judges and practising lawyers

have taken the position that it

is in the best interests of children that they participate in decisions that affect them and that they be

listened to and taken seriously. As a Superior Court justice noted:

11

Another myth that needs to be dislodged is that harm befalls a child from

participating in the decision-making process. This has often been a

rationalization for leaving the child’s voice out. Some experts feel it can

be harmful for the child to be left out of the decision- making process. The

more paternalistic approach overlooks the reality that the child is already

harmed by the turmoil in his home and the stress that litigation has

brought upon everyone.

The voice of the child is now a predominant consideration when identifying the factors relevant for

creating parenting plans among separating families. The social science and legal literature identify

the risks and benefits of listening to the voice of the child.

12

There is a substantial body of research

that indicates that children want input into family matters that affect them, that they want to be

heard, they want to be made aware of the circumstances that impact them and they want to have a

voice in identifying what is important to them.

13

Children also express how they wish to be engaged

in processes involving them even if they are not making final decisions.

14

Moreover, listening to

Children: An Overview”. (1996) 10:2 Children and Society 934-944; Nicola J. Taylor, Anne B. Smith & Pauline Tapp,

“Children, Family Law and Family Conflict: Subdued Voices”. (1999)

7

Robert E. Emery, “Children’s Voices: Listening—And Deciding—Is an Adult Responsibility” (2003) 45 Arizona Law

Review 621–627. Richard A. Warshak, “Payoffs and Pitfalls of Listening to Children” (2003) 52 Family Relations 373-

384.

8

Carole Smart, “From children’s shoes to children’s voices” (2002) 40:3 Family Court Review 307-319.

9

A. O’Quigley, “Listening to children’s views: The findings and recommendations of recent research” (2000) York:

Joseph Rowntree Foundation; J. Timms, “The Silent Majority—The Position of Children Involved in the Divorce and

Separation of Their Parents” (2003) 9:2 Child Care in Practice 162-175.

10

Supra note 1.

11

Judge A. P. Nasmith, “The Inchoate Voice” (1991-92), 8 Can. Fam. L.Q. 43-54.

12

Supra note 1.

13

Supra note 1.

14

Supra note 2

10

children’s voices is supported in the research as it contributes to parental harmony and less

conflict.

15

,

16

The extent to which children’s voices can be heard will depend on the adults involved and whether

they are willing to listen to children and able to incorporate the children’s input in post-separation

decision making.

17

This means that voice of the child is impacted by different people and different

processes. Practically speaking, these factors make it important for service providers and

professionals to ensure that the child who voices their views has the capacity to do so and is not

impaired by the influence or circumstance brought upon them by, for example, the level of parental

conflict.

There is growing interest in many countries around the world to incorporate children's views in

court proceedings. This is largely due to the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the

Child. Article 12 of this Convention requires that States party to the Convention:

1. Assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the

right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the

views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and

maturity of the child.

2. For this purpose, the child shall in particular be provided the

opportunity to be heard in any judicial and administrative proceedings

affecting the child, either directly, or through a representative or an

appropriate body, in a manner consistent with the procedural rules of

national law.

18

Article 3 of the Convention states:

1. In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or

private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities

or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary

consideration.

After Canada ratified the Convention in 1991,

19

the Special Joint Committee on Child Custody and

Access recommended in 1998 that children in Canada have the opportunity to “be heard when

parenting decisions affecting them are being made” and to “express their views about the separation

15

Jill Goldson, “Hello, I’m a Voice, Let Me Talk: Child-Inclusive Mediation in Family Separation” (2006) Center for

child and family policy research, Auckland University.

16

Jennifer McIntosh, “Child Inclusion as a Principle and as Evidence-Based Practice: Applications to Family Law

Services and Related Sectors” (2007) AFRC Issues: Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse.

17

Rachel Birnbaum & Michael Saini, “A Scoping Review of Qualitative Studies about Children Experiencing Parental

Separation” (2013) 20:2 Childhood 260-282.

18

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol.

1577, p. 3.

19

Jean-Francois Noel, “The Convention of the Rights of the Child” (2015) Department of Justice. Available online at

https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/fl-lf/divorce/crc-crde/conv2a.html

11

or divorce to skilled professionals whose duty it would be to make those views known to any judge,

assessor, or mediator making or facilitating a shared parenting determination.”

20

Canadian courts have referenced Article 12 of the Convention in their decisions dating back to the

1990s,

21

as they are working with the principle that children’s views are a vital component of the

family law process when taken together with other factors. Former Justice Donna Martinson’s

widely cited 2010 decision of the Supreme Court of Yukon highlights children’s views as a vital

component of the decision-making process in family law:

. . . in my respectful view all children in Canada have legal rights to be

heard in all matters affecting them, including custody cases. Decisions

should not be made without ensuring that those legal rights have been

considered. These legal rights are based on the United Nations Convention

on the Rights of the Child and Canadian domestic law.

The Convention . . . says that children who are capable of forming their

own views have the legal right to express those views in all matters

affecting them, including judicial proceedings. In addition, it provides that

they have the legal right to have those views given due weight in

accordance with their age and maturity. There is no ambiguity in the

language used. The Convention is very clear; all children have these legal

rights to be heard, without discrimination. It does not make an exception

for cases involving high-conflict, including those dealing with domestic

violence, parental alienation.

A key premise of the legal rights to be heard found in the Convention is

that hearing from children is in their best interests. Many children want to

be heard and they understand the difference between having a say and

making the decision. Hearing from them can lead to better decisions that

have a greater chance of success. Not hearing from them can have short

and long term adverse consequences for them. While concerns are raised

by some, they can be dealt with within the flexible legal framework found

in the Convention.

22

The court then goes on to list all the manners in which children should participate in their own legal

proceedings, and where the participation must be meaningful, which include that children should:

1. be informed, at the beginning of the process, of their legal rights to be

heard;

2. be given the opportunity to fully participate early and throughout the

20

Parliament of Canada, For the Sake of the Children: Report of the Special Joint Committee on Child Custody and

Access (December, 1998)

21

Johns v Hickson, [1996] S.J. No. 806 at para 9; P (CL) v P (JE), 2015 SKQB 13 at para 16; Seymour v Seymour, 2012

SKQB 161 at para 88.

22

2010 YKSC 44 at para 47. Followed in: Children's Aid Society of Algoma (Elliot Lake) v PC-.F, 2017 ONCJ 898;

Nunavut (Director of Child and Family Services) v T (E), 2017 ONCJ 898; K (NJ) v F (RW), 2011 BCSC 1666;

Jarvis v Landry, 2011 NSSC 116.

12

process, including being involved in judicial family case conferences,

settlement conferences, and court hearings or trials;

3. have a say in the manner in which they participate so that they do so in

a way that works effectively for them;

4. have their views considered in a substantive way; and

5. be informed of both the result reached and the way in which their views

have been considered.

23

Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child indicates that the views of the child shall

be given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child, including the opportunity

to be heard in any judicial proceeding. The expectation is limited to children who are capable of

forming their own views and does not provide directives on how best to assess children’s capacity

to have their voices heard. For example, given that children mature and develop at different rates,

the Convention does not specify an age at which children attain capacity, nor does the Convention

define “capacity.”

The General Comment No.12 of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child anticipates that

children will have a sufficient understanding of the issues on which they are giving their views, but

not a comprehensive understanding.

24

As the complexities of the issues surrounding a child’s input

into decisions increase, the demand for maturity increases proportionately. By way of example,

given that many professionals have difficulty fully understanding the complexities of high conflict

families, it is naive to think that a child or even an adolescent will.

The question of whether children should be given a voice in custody and access disputes has been

answered by most in the affirmative. However, the question has now transformed to how that

participation should take place.

25

The Convention does not specify how children’s voices should be

heard. From research and practical perspectives, there remains debate in the literature about the

strengths and limitations of the various approaches for facilitating children’s voices within family

justice processes.

The discussion above documents the historical shift in the role and presence of the voice of the child

in family law. The role of the Convention and Canadian case law demonstrates that children’s

voices should be considered in family law matters that affect them. One of the most pressing issues

on the voice of the child in family law is simply how best to hear from children. In what follows,

the report examines the different ways in which the court can hear a child’s views and preferences,

and explores the merits and shortcomings of each approach.

23

2010 YKSC 44 at para 47. Followed in: Children's Aid Society of Algoma (Elliot Lake) v PC-.F, 2017 ONCJ 898;

Nunavut (Director of Child and Family Services) v T (E), 2017 ONCJ 898; K (NJ) v F (RW), 2011 BCSC 1666; Jarvis v

Landry, 2011 NSSC 116.

24

Convention on the Rights of the Child, Committee on the rights of the Child, Fifty-first session, (Geneva, 25 May-12

June 2009).

25

Carolyn Savory, “A Voice for "The Small": Judicial "Meetings" in Custody and Access Disputes” (2013) 28

Canadian Journal of Family Law at 227.

13

Chapter 3: Brief Review of Children’s Experiences of Providing Voice

This section provides a summary of the experiences of children providing their views in family law

matters.

26

Increasingly children and youth are expressing that they want to share their “voice” in the

decision-making processes that fundamentally affect their lives post-separation. The research on

children’s desire to be included suggests that they want to be kept informed, and want their needs

and interests heard, but usually do not expect to make decisions. Adolescents are much more likely

to be involved when major decisions affecting them are made, and to want to express explicit

preferences about these decisions.

27

Children’s Input into Parenting Plans

Research suggests that despite advances in actively involving children, children have largely

remained absent from the decision-making process during parental separation and/or divorce.

28

Qualitative studies of children’s experiences of providing input into parenting plans consistently

show that, despite wanting to have their voices heard, many children report not being provided the

opportunity to provide their input.

29

According to one study, for example,

30

half of children report

no involvement in the decision of where they will live following parental separation. Other research

indicates

31

that youth are typically unsure of their rights, and youth report that adults, including their

parents, do not listen to them. Those who have “some say” are typically adolescents at the time of

parental separation. Children who report having some say in the decision making about parenting

plans were generally satisfied that their views were considered.

32

Children also describe wavering between wanting to be involved and feeling hurt by the processes

of their parents’ separation. While children want to be treated with respect and as capable of being

involved in the process, they also describe feelings of vulnerability, change and loss.

33

A study in

26

Judith Cashmore & Patrick Parkinson, “Children’s and Parents’ Perceptions on Children’s Participation in Decision

Making after Parental Separation and Divorce” (2008) 46 Family Court Review 91–104.

27

Stephanie Holt, “The Voice of the Child in Family Law: A Discussion Paper” (2016) 68 Children and Youth Services

Review 139-145; Patrick Parkinson, Judith Cashmore & Judi Single, “Adolescents' Views on the Fairness of Parenting

and Financial Arrangements After Separation” (2005) 43:3 Family Court Review 429-444; Anne Stafford, A. Laybourn,

Malcolm Hill & Moira Walker, “Having a Say’: Children and Young People Talk about Consultation” (2003) 17

Children & Society 361-373.

28

Judith Cashmore, “Children's Participation in Family Law Decision-Making: Theoretical Approaches to

Understanding Children's Views” (2011) 33:4 Children and Youth Services Review 515-520; Christina Sadowski &

Jennifer E. McIntosh, “On Laughter And Loss: Children's Views of Shared Time, Parenting And Security Post-

Separation” (2016) 23:1 Childhood: A Global Journal of Child Research 69-86; Sofie D. J. Maes, Jan De Mol & Ann

Buysse, “Children’s Experiences and Meaning Construction on Parental Divorce: A Focus Group Study” (2012) 19:2

Childhood: A Global Journal of Child Research 266-279.

29

Anne Graham, Robert Fitzgerald & R. Phelps, “The Changing Landscape of Family Law: Exploring the Promises and

Possibilities for Children’s Participation in Australian Family Relationship Centres” (2009) Lismore: Southern Cross

University; C. Brand, G. Howcroft & C. N. Hoelson, “The Voice of the Child in Parental Divorce: Implications for

Clinical Practice and Mental Health Practitioners” (2017) 29:2 Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health 169-

178.

30

Parkinson, supra note 27.

31

C. Reeves, “Youth Included! Youth Recommendations for Children and Youth Participation in British Columbia’s

Family Justice System” (2008) The Social Planning and Research Council of British Columbia.

32

Cashmore, supra note 28.

33

Supra note 6.

14

Scotland found that children’s voices can be overlooked and/or dismissed when the parents are

preoccupied with the interparental conflict.

34

Reasons why Children want their Voices Heard

Children want the opportunity to express their views within custody disputes and feel that their

voices should be represented in discussions about their living arrangements and relationships with

their parents. Children express a number of reasons for why they think it is important to have their

voices heard, including wanting to be acknowledged as an important voice in the family dispute and

to be better informed about parenting plan decisions.

35

Children emphasize the importance of fairness and equal opportunity to be part of the decision-

making process

36

and that they want to be consulted.

37

Other reasons for wanting to be heard

include to make sure that the decisions reflect their needs and to be made aware of the parenting

plan so that they are more informed and better able to cope with changes and transitions.

38

When

children aged eight to twelve years rank, in order of importance, a number of reasons why children

should be involved in decision making, children consistently put at the top of their lists: “to be

listened to”; “to let me have my say”; “to be supported”, and at the bottom: “to get what I want.”

39

Although some adults may perceive that children’s voices in family justice matters equates with

allowing children to become the sole decision-makers, it appears that many children actually want

an opportunity to express their views and be heard, not the power to ultimately make custody and

access decisions.

40

34

Gill Highet & Lynn Jamieson, “Cool with Change: Young People And Family Change (Final Report)” (2007)

Scotland’s Families/Centre for Research on Families and Relationships.

35

Rachel Birnbaum, Nicholas Bala & Francine Cyr, “Children’s Experiences with Family Justice Professionals and

Judges in Ontario and Ohio” (2011) 25 International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 398–422.

36

Dale Bagshaw, “Reshaping Responses to Children When Parents Are Separating: Hearing Children’s Voices in the

Transition” (2007) 60 Australian Social Work 450–465; Alan Campbell, “The Right to Be Heard: Australian Children’s

Views about their Involvement in Decision-Making Following Parental Separation (2008) 14 Child Care in Practice

237–255; Tapologo Maundeni, “Seen but not Heard? Focusing on the Needs of Children of Divorced Parents in

Gaborone and Surrounding Areas, Botswana” (2002) 9 Childhood 277–302.

37

Alan Campbell, “The Right to Be Heard: Australian Children’s Views about their Involvement in Decision-Making

Following Parental Separation” (2008) 14 Child Care in Practice 237–255.

38

Rachel Birnbaum, “Listening to Youths about their Needs and Preferences for Information Relating to Separation

and/or Divorce” (2007) Department of Justice, Family, Children, and Youth Section, Justice, Canada.

39

N. Thomas & C. O’Kane, “Children’s Participation in Reviews and Planning Meetings when they are ‘Looked After’

in Middle Childhood” (1999) 4 Child & Family Social Work 221-230.

40

Maria Coley, “Children’s Voices in Access and Custody Decisions: The Need To Reconceptualize Rights and Effect

Transformative Change (2017) 12 Appeal 49-72 Available online at

https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/appeal/article/viewFile/5454/3397

15

Children’s Capacity in Decision-Making

Several factors are generally considered with respect to the capacity of children and adolescents to

make decisions including age, context and development.

41

The amount of weight given to the

child’s voice increases proportionally with the age of the child.

42

Children and adolescents are not

generally invited to share their views in final decision-making post-separation, yet the weight

assigned to their voice and their input as they get older is often akin to determination.

When assessing children’s capacity to provide input, it is also important to consider the context of

the family dynamics. For example, in family breakups that include higher levels of interparental

conflict, children’s age should not be the only factor to consider. Older children and adolescents

experiencing interparental conflict can be more vulnerable to the influence of their parents and

therefore the extent to which their decisions are independent is questioned.

43

When stuck in their

parents’ conflict, some children may be motivated to protect their relationships with their parents

and may not want to upset their parents by expressing views that may be contrary to the

expectations of their parents. When these factors prejudice children’s input, there is a question as to

what their independent views might be if they were isolated from these dynamics. Moreover,

children attempt to predict what they believe their parents wish to hear, which often results in

inconsistent statements of their wishes.

44

Effects of Children’s Participation

Researchers have come to recognize the advantages of talking directly to children about their

experiences with sharing their views of parenting plans, rather than relying on reports mediated by

adults.

45

Child participation is considered essential to making good decisions that affect children,

whether the child is a party to court proceedings, the subject of a proceeding, a witness or an

affected third party to the decision-making.

46

Children’s lived experiences are considered distinct

from those of adults and considering these experiences can help make legal decisions better for the

children.

Researchers report that children generally view their participation in family justice services as

beneficial.

47

Including children’s voices in decision making contributes directly to their well-being

and adjustment, and can help them cope more effectively with the transitions of separation and

divorce.

48

Including children in parenting plan determinations may also increase their feelings of

41

P. Grootens-Wiegers, I. M. Hein, J. M. van den Broek, & M. C. de Vries, “Medical Decision-Making in Children and

Adolescents: Developmental and Neuroscientific Aspects (2017) 17:1 BMC Pediatrics 120.

42

Joanne Paetsch, Lorne Bertrand, Jan Walker, Leslie MacRae & Nicholas Bala, “Consultation on the Voice of the

Child at the 5th World Congress on Family Law and Children’s Rights” (2009) [unpublished]

43

Kirk Weir, “High Conflict Disputes: Evidence of the Extreme Unreliability of Some Children Ascertainable Wishes

and Feelings” (2011) 49:4 Family Court Review 788-800.

44

Ibid

45

Carrie Brand, Greg Howcroft & Christopher Norman Hoelson “The Voice of the Child in Parental Divorce:

Implications for Clinical Practice and Mental Health Practitioners” (2017) 29:2 Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental

Health 169-178.

46

Supra note 40.

47

Supra note 6.

48

Joan Kelly, “Psychological and Legal Interventions for Parents and Children in Custody and Access Disputes:

Current Research and Practice” (2002) 10 Va. J. Soc. Pol’y & L. 12.

16

competency and independence.

49

The most significant theme emerging from the research is the

importance of keeping children informed, respecting their views, listening to them, and considering

them in decision making.

Conversely, excluding children from meaningful participation in parenting plan decisions can have

a negative impact on their overall adjustment and understanding of the separation process. Research

suggests that when children are excluded from parenting plan decisions, they can feel more

distressed, insecure, rejected and angry.

50

Children report a sense of helplessness due to the lack of

control and limited input they have regarding divorce-related decisions.

51

Many of these children

experience confusion due to the failure of their parents to explain divorce-related decisions.

52

Children’s Advice

Children’s main advice for other children experiencing parental separation is not to let their parents

decide on parenting arrangements alone and to talk to adults, including their parents, mental health

professionals and legal professionals, about what they want to happen in terms of the parenting plan

post-separation and divorce. Studies indicate that children believe that other children should be

consulted and that they should have someone they could talk with about their adjustment problems

(e.g., parents, friends, counsellor, a judge).

53

Children state that they should be included in

decisions, they should be provided the opportunity to share their views and they should be able to

talk about their feelings about the separation and divorce. They also suggest that sharing their views

should not compromise their relationship with their parents.

Children’s advice for professionals working with children post-separation is to talk less and listen

more, get to know the children outside of the parental conflict, including their hobbies and interests.

Children also want more feedback about what is happening in the decisions regarding the parenting

plans.

54

Summary

This chapter reviews experiences of children providing their views in family law matters. Children

are increasingly expressing a desire to share their “voice” in the decision-making processes in

family justice processes that fundamentally affect their lives. Research emphasises the importance

of considering the voice of the child, giving children the opportunity to share their voices, and

giving sufficient weight to children’s views based on the age, developmental stages and capacity to

make decisions that affect them. The next chapter considers the various methods that have been

49

Supra note 46.

50

Supra note 48.

51

Nancee Biank & Catherine Ford Sori, “Encouraging Children’s Stories of Divorce” (2012) 4 Journal of Clinical

Activities Assignments & Handouts in Psychotherapy Practice Assignments & Handouts in Psychotherapy Practice 15-

40.

52

Wendy Sturgess, Judy Dunn & Lisa Davies, “Young Children’s Perceptions of Their Relationships with Family

Members: Links with Family Setting, Friendships, and Adjustment” (2001) 25:6 International Journal of Behavioral

Development 521–529.

53

Supra note 36.

54

Rhonda Bessner, “The Voice of the Child in Divorce, Custody and Access Proceedings” (2002) Family, Children and

Youth Section, Department of Justice Canada, 2002-FCY-1E.

17

developed both within Canada and abroad as means for hearing the voices of children in family

justice services.

Chapter 4: Methods for Including Children’s Voices in Family Law Matters

Methods for including children’s voices in family matters are situated along a continuum of

litigation involvement, from services outside of the court process (e.g., child-inclusive mediation

services) to methods embedded within the context of litigation (e.g., judicial interviews). Framing

methods for including children’s voices along the continuum of the legal process helps to

underscore the many services provided to children as their parents follow the various pathways of

the family justice system. The continuum also helps to identify and consider the various

opportunities afforded to children to provide their views and preferences about parenting plan

decisions. The continuum further underscores the gaps in services for hearing children’s voices

within the context of separation and divorce.

Exploring opportunities for including children’s voices in the continuum of the legal process

provides a framework for exploring, not just the opportunities for children’s voices to be heard

within the courts, but also the opportunities for children to have greater voice earlier in the

separation and process. Not all children’s parents will be engaged in the family justice system to

resolve their disputes and there is a current focus to move families out of court quicker and into

dispute resolution services to resolve their disputes without court involvement.

55

Given that the vast

majority of separating parents will settle their parenting plan disputes without substantial legal

involvement, and that they will usually settle their disputes within one year of initial application to

the courts,

56

providing only court-based methods for including children’s voices eliminates

opportunities for a substantial number of children to have their voices included in parenting plan

decisions.

Although there is much less attention to earlier opportunities to have children’s voices heard

(mostly because the case law is more specific to the legal side of children’s voice), it is nevertheless

important to consider opportunities both within and outside of the court process for hearing

children’s voices. To support children’s voices both within court processes and outside of the

courts, the consideration of the various methods for including children’s voices in services that fall

along the continuum from a processes outside of the courts to methods embedded in the context of

litigation.

Non-Court Child Inclusive Methods

Although not directly part of the family justice system, it is nevertheless important to consider non-

court related approaches for hearing children’s voices given that the majority of children will not be

offered opportunities to speak to a judge, lawyer, or court-based mediator or mental health

professional about their views of parenting plans that affect them.

57

When parents are not directly

55

Michael Saini, Rachel Birnbaum, Nicholas Bala & Brenden McLarty, “Understanding Pathways to Family Dispute

Resolution and Justice Reforms: A Court File Analysis & Survey of Views of Professionals in Ontario” (2016) 54:3

Family Court Review 382-397.

56

Mary Allen, “Profile of Child-Related Family Law Cases in Civil Court” (2013) Available online at

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2013001/article/11781-eng.htm.

57

Supra note 55.

18

involved in the family justice system to resolve their parenting disputes, children can become

silenced in the decision-making process.

Children Talking with Parents

Family law problems can be resolved in various ways and court is not the only option for parents.

Some view out-of-court dispute resolution processes and resolution through agreements as the

preferred option for solving parenting disputes, with court-based resolution processes being a

valued, but not always necessary.

58

When parents agree to parenting plans outside of the court, there

has been little focus in the literature about how best to engage children’s voices into these decisions.

Children discuss the desire to be part of the decision-making process at earlier stages in the divorce

process, including at the point where the parents decide to separate.

59

For some children,

particularly for those whose parents resolve their disputes without legal involvement, speaking with

their parents may be the opportunity to have input in the parenting plan and to share their views and

preferences.

There are several challenges associated with children sharing their views with their parents. Most

children report that their parents do not provide them with adequate opportunity to be part of

conversations about parenting plans post-separation.

60

Studies of children’s perspectives of their

parents’ separation indicate that children do not receive adequate support during their parents’

separation, are not given sufficient explanations of what is happening to their families, and most

have no input into parenting plan determinations.

61

Parents may not be emotionally ready to hear

their children, as separated parents have been found to show decreased parenting competency post-

separation.

62

Parents may have lower emotional availability and sensitivity for their children during

this time.

63

Parents may also continue to blame the other parent for the family breakdown and may

participate in negative disclosures about the other parent, which has been found to affect the child’s

closeness and satisfaction with their parents.

64

Being placed in the middle of their parents’ dispute

can feel overwhelming for children and can induce feelings of guilt.

Children can be further put in the middle of their parents’ dispute if the parents eventually decide to

use the courts to resolve disagreements and carry with them their child’s views to augment their

arguments to the courts. In these cases, the courts have noted that parents may have a vested interest

in misrepresenting the child’s views, or pressuring the child to express a certain view. As the court

in M (DG) v M (KM) noted, since parents “clearly ha[ve] a personal stake in the outcome of the

58

Peter Salem & Michael Saini, “A Survey of Beliefs and Priorities About Access to Justice of Family Law: The Search

for a Multidisciplinary Perspective” (2017) 55:1 Family Court Review 120–138

59

Supra note 36.

60

Judith Cashmore & Patrick Parkinson, “Children's and Parents’ Perceptions on Children's Participation in Decision

Making after Parental Separation and Divorce” (2008) 46 Family Court Review 91-104.

61

M. Gollop, A.B. Smith & N.J. Taylor, “Children's Involvement in Custody and Access Arrangements” (2000) 12:4

Child and Family Law Quarterly 396-399.

62

Michael Saini, “Reconceptualizing High-Conflict Divorce as a Maladaptive Adult Attachment Response” (2012) 93:3

Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services 173-180.

63

Katie E. Sutherland, Shannon Altenhofen & Zeynep Biringen, “Emotional Availability during Mother–Child

Interactions in Divorcing and Intact Married Families” (2012) 53:2 Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 126-141.

64

Tamara D. Afifi, & Tara McManus, “Divorce Disclosures and Adolescents' Physical and Mental Health and Parental

Relationship Quality” (2010) 51:2 Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 83-107.

19

proceedings,”

65

courts should use caution when children’s views are reported via a parent.

Additionally, some courts may question children’s views being too similar to a parent’s position in

litigation, and will give them less weight when this occurs, seeing this as an indication of parents’

views unduly influencing by the child.

66

Most jurisdictions in Canada provide parent education programs for separating and divorcing

parents to provide them with information, skills, and development activities to help them better

cope with the family breakdown and to focus their attention on the needs of the children. Very few

of these programs actually focus on how to talk with children about their views on parenting plan

issues while protecting them from the conflict. For example, the Parenting After Separation

program in British Columbia

67

includes the goals of helping parents make careful and informed

decisions about their separation and to ensure that these decisions are based on the best interests of

their children. There is no mention of whether parents are informed about how best to listen to their

children post-separation.

Children Sharing their Views with Professionals

When children do not feel comfortable talking with their parents about their experiences with

parental separation and views about the parenting plan, they may turn to professionals. For example,

recent research identifies children speaking with their teachers and mental health professionals

about their views and preferences on parenting plan arrangements. School teachers may not be the

best adults for children to share their views about parenting plans with, as research finds that school

staff are often ill-equipped to listen to children about their parents’ separation. They often lack the

expertise for directing children to the appropriate services.

68

Teachers can face legal and ethical

challenges when working with students and their families and many are discouraged from becoming

involved in child custody matters.

69

The role of mental health professionals (e.g., child protection workers, therapists), in hearing

children’s views about post-divorce arrangements has become more prominent.

70

Mental health

professionals, however, may lack the training for working with children post-separation and

divorce. For example, a recent survey of child protection workers in Ontario found that the child

protection workers often feel pressured to take sides in the parents’ disputes and prematurely close

their files without considering the views of children in these disputes.

71

Parent coaching has recently emerged as a specialized service for separating and divorcing parents

serving as an informed educator and consultant to the parents. The parent coach, usually a mental

65

2000 ABQB 593 at para 24.

66

Milliker v Milliker, 2005 SKQB 455 at para 32.

67

Parenting After Separation. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/life-events/divorce/family-justice/who-can-help/pas

68

Linda Mahony, Kerryann Walsh, Joanne Lunn, & Anne Petriwskyj, “Teachers Facilitating Support for Young

Children Experiencing Parental Separation and Divorce” (2015) 24:10 Journal of Child and Family Studies 2841-2852.

69

C. E. Hatton, “The Experiences of School Counselors with Court Involvement Related to Child Custody”

(2015) Available from PsycINFO. (1694709828; 2015-99131-088).

70

C. van Nijnatten & E. Jongen, “Professional Conversations with Children in Divorce-Related Child Welfare

Inquiries” (2011) 18:4 Childhood: A Global Journal of Child Research 540-555.

71

Michael Saini, Tara Black, Elizabeth Godbout & Sevil Deljavan, “Feeling the Pressure to take Sides: A Survey of

Child Protection Workers’ Experiences about Responding to Allegations of Child Maltreatment within the Context of

Child Custody Disputes” (2019) 96 Children and Youth Services Review 127-133.

20

health professional, typically has specialized knowledge of the effects of family breakdown,

knowledge regarding the legal system, and competence in the skills necessary for effective

coaching.

72

When parent coaching includes child-inclusive frameworks, the children are typically

included and receive education and support for sharing their views with their parents.

There are also a variety of existing programs for children experiencing parental separation and

divorce, most of which are intended to provide children with the opportunity to express their voices

and needs within the context of their parents’ separation and divorce disputes. These programs do

not appear to be widely available across Canada.

73

In addition, these programs do not afford the

opportunity for children to have input into parenting plan decisions.

Child-Inclusive Mediation

Children’s participation in mediation, a dispute resolution process to help parents resolve conflict,

varies widely across Canada, and even within individual provinces and territories. Many Canadian

provinces now offer mediation to separating or divorcing parents to assist families resolve parenting

plan issues outside of court.

Child-inclusive mediation brings the child into the process of family dispute resolution. In one

model, for example, a child specialist is engaged in the process to interview the child to gain an

understanding of the child’s emotional needs, and expressed wishes.

74

The child specialist then

participates in the mediation with the parents, incorporating the child’s perspective on child-related

issues in the mediation session without subjecting the child to the adult session or requiring the

parents to modify the session due to the child’s presence.

75

Commentators and researchers are divided over whether, and how, children should be included in

their parents’ mediation concerning parenting plan issues. Proponents argue that including children

gives them a sense of control over their fate, a place to express and deal with feelings they may not

be expressing to their parents, and lets them know what is happening.

76

Opponents argue that it is in

children’s best interests not to be included in mediation because it places children in the middle of

their parents’ dispute and burdens children with the responsibility of making adult decisions.

77

Results from the social science research suggest that involving children in mediation can have a

positive effect on mediation outcomes, including agreements with more parenting time for non-

residential parents and more communication provisions.

78

Some research suggests that parents and

72

Lindsey N. Plante, “Ending in A Way that Allows for New Beginnings: A Divorce Coaching Curriculum” (2014)

Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology, Ann Arbor.

73

O’Connor, supra note 1.

74

Jennifer McIntosh, “Child-Inclusive Divorce Mediation: Report on a Qualitative Research Study” (2000) 18:1

Mediation Quarterly 55-69.

75

Stacey Platt, “Set another Place at the Table: Child Participation in Family Separation Cases” (2016) 17 Cardozo 749-

765.

76

Ibid.

77

Robert Emery, “Children’s Voices: Listening—and Deciding—is an Adult Responsibility” (2003) 45 Ariz. L. Rev.

621.

78

R. H. Ballard, “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Child Informed Mediation” (2013) Available from ProQuest

Dissertations & Theses Global: Health & Medicine; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: Social Sciences.

(1425265132).

21

children in child-inclusive mediation believe that children gain a sense of relief, a lighter burden, a

clearer perspective, and the experience of being heard.

79

Child-inclusive mediation also has been

found to decrease court motions following the final resolution of issues addressed in mediation.

80

Child-inclusive mediation provides the children of separating families an opportunity to be heard. It

is, moreover, an essential opportunity for disputing parents to focus on children’s needs and wishes.

The financial and emotional savings to families from successful mediation, removing the need for

costly, lengthy, and profoundly negative legal processes and trials, may well justify the additional

cost of including children in the mediation process. Providing child-inclusive mediation for families

experiencing lower levels of conflict can also free judges to hear and determine only the most

intractable cases. Even in cases that do not settle, children benefit from child-inclusive mediation

processes, knowing that their parents care about how they feel and knowing that their parents are

making attempts to settle the parenting dispute peacefully. Disadvantages of child-inclusive

mediation include instability of government funding to support these programs. Including children

in the mediation process can also increase the cost of mediation given the extra cost of including a

child specialist to interview the children and then report back to the mediator.

81

Court Based Child-Inclusive Methods

Many of the court-related child-inclusive methods for hearing the voices of the child are primarily

in the context of helping the court in its decision-making as opposed to having children contribute

to the decision-making in concert with their parents. Several Canadian and international pilot

studies have been developed to better respond to children’s voices within the context of court-based

disputes regarding parenting plans. Many of these seem promising, but further evaluation is needed

to assess the impact of listening to children and integrating their voices in parenting plan disputes.

Child-Inclusive Conferencing

Most recently, the Australian family courts developed a new service to involve children’s voices

within their parents’ disputes at the initial stages of court involvement. Child Inclusive

Conferencing involves a meeting with the parents and children with a Family Consultant, qualified

social workers or psychologists, ordered by the court and without the presence of lawyers. The

Child Inclusive Conference is intended to give the court an understanding of the family situation,

and particularly of the children’s experience.

82

According to the model, the Family Consultant interviews each parent and the children and then

assists the court by making suggestions about what needs to be considered for the children. The

Family Consultant also provides an opportunity for the parties to discuss arrangements for the

79

Supra note 74.

80

B. N. Rudd, R. K. Ogle, A. Holtzworth-Munroe, A. G. Applegate & B. M. D'Onofrio, “Child-Informed Mediation

Study Follow-Up: Comparing the Frequency of Relitigation Following Different Types of Family Mediation” (2015)

21:4 Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 452-457.

81

Supra note 75.

82

Family Court of Australia. Child Inclusive Conferencing Fact Sheet. (nd) Available at

http://www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fcoaweb/reports-and-

publications/publications/child+dispute+services/child-inclusive-conferences.

22

children and negotiate their own agreement. The process usually involves the Family Consultant

first speaking with the adults and then with the children about what has been happening and what is

important to them. After seeing the children, the Family Consultant may give feedback to the adults

about the children’s views and preferences.

Child Inclusive Conferencing is unique to Australia and has been developed by court-based mental

health professionals with very little statutory and regulatory guidance. While there are no known

Child Inclusive Conferencing in Canada, recent research from Australia details

83

how this can be

effectively implemented. Results based on a small sample of Family Consultants balance the right

of the child to be heard with the responsibility to ensure the child’s safety and the child’s best

interests. Furthermore, the Family Consultants suggest that to truly listen to the views of the child,

the child needs to have a more substantial role in identifying and determining what is in their best

interests and deciding what matters that affect them. The Family Consultants reported that they

considered how much weight the court might give to the child’s views in their decision making.

Based on these findings, Child Inclusive Conferencing could serve as a framework to guide the role

of Family Consultants or other similar professionals within Canadian family justice processes. Child

Inclusive Conferencing seems to provide an important model for including children’s voices within

court-based services and has the potential of providing children with meaningful contributions to

parenting plan decisions while also protecting their safety and their relationships with their parents.

However, research would need to be conducted in Canada on a pilot basis to determine the fit of

Child Inclusive Conferencing within existing family justice services.

Appointment of Children’s Lawyer

Different provinces offer different options for child representation. Ontario has the most

comprehensive method for representing children, through the Office of the Children’s Lawyer

(OCL), which is empowered to litigate custody and access issues. In Prince Edward Island, there is

no legislation for child representation in family law matters, but they do have an Office of the

Children’s Lawyer. In Quebec, a child has the right to be heard, meaning that a lawyer will be

appointed for them as soon as they wish to exercise this right. Limited resources exist in Nova

Scotia for a child’s lawyer to be appointed. This is in comparison to Alberta, Quebec, New

Brunswick, Nunavut and the Yukon, which have no equivalent government office, and where the

courts appoint Legal Aid lawyers for children when needed. In British Columbia, children are not

considered parties for the purposes of legal aid and as a result, assessments are more common than

full representation.

Studies in Canada and abroad have found that most children are supportive of having a lawyer

represent them in court. Most children are satisfied with their legal representation as they believe

their lawyers are neutral, objective, and trustworthy.

84

In contrast, other studies have noted that

children generally do not benefit from talking to lawyers as these children feel that representation

was more like intervention and discussions felt like interrogations.

85

83

Vicki Banham, Alfred Allan, J. Bergman & Jasmin Jau, “Acknowledging Children’s Voice and Participation in

Family Courts: Criteria that Guide Western Australian Court Consultants” (2017) 5:3 Social Inclusion 155-163.

84

Rachel Birnbaum & Nicholas Bala, “The Child's Perspective on Legal Representation: Young Adults Report On

Their Experiences with Child Lawyers” (2009) 25:1 Canadian Journal of Family Law 11-71.

85

Alan Campbell, “For Their Own Good: Recruiting Children for Research” (2008) 15:1 Childhood 30–49.

23

With different possibilities across Canada for appointing a lawyer for a child, courts have also taken

different approaches. For example, in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice decision in Collins v

Petric, the court sets out three instances where it is not necessary to appoint a lawyer for a child,

including where: a full assessment has been made; the appointment of a lawyer would significantly

delay the proceeding; or the introduction of a new party might be upsetting for the child.

86

The Quebec Court of Appeal in F (M) v L (J) has stated that if a child is mature enough to have an

opinion, a low threshold, then the child’s lawyer has a duty to advocate this position.

87

The

appointment of a lawyer cannot be tied into the parties’ litigation. Otherwise, there exists an

understandable concern that the child’s representative will not be neutral to the parent’s interests.

Advantages of child legal representation include that children may benefit from having their own

advocate to explain the court proceedings to them, including possible case outcomes. Children’s

legal representation may informally help parents settle disputes and refocus attention on the child’s

needs. Disadvantages of child legal representation include some children not feeling they benefit

from talking to lawyers, preferring instead to keep family issues within the family. Further, some

children do not respond well to interactions with their lawyers.

88

It is also important to point out that

the high cost of legal representation and the limited funds and resources to publicly support these

programs limit the number of children who are able to access the services.

Children Interviews of Children within Parenting Plan Assessments

A significantly less direct way to incorporate a child’s voice within court-based processes is through

the involvement of a court-appointed or private parenting plan assessor. This assessor completes a

comprehensive parenting plan assessment and makes a report to the court. Psychiatrists,

psychologists, social workers, and other mental health professionals routinely conduct these

parenting plan assessments.

There are differing models across Canada for how costs are allocated for parenting plan

assessments. For example, in Nova Scotia, the costs associated with assessments are shared between

the court, the Nova Scotia Department of Justice, and the parents if they earn more than $20,000 per

year.

89

In Manitoba, free parenting plan assessment reports are provided through Family

Conciliation, a branch of Family Services and Housing.

90

In Ontario, parenting plan assessments

can be conducted both by the government at no charge to the parents and for a fee by a private

assessor.

The primary goal of the child’s interview within the parenting plan assessments report is to assist

judges, lawyers, and families by providing expert opinions regarding the level of inter-parental