REPORT ON

FEDERAL-PROVINCIAL-TERRITORIAL

CONSULTATIONS

Fall 2001

Custody,

Access and

Child Support

in Canada

Custody, Access and

Child Support in Canada

REPORT ON

FEDERAL-PROVINCIAL-TERRITORIAL

CONSULTATIONS

Presented to the

Federal-Provincial-Territorial Family Law Committee

Prepared by

IER Planning, Research and Management Services

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the views of

the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Family Law Committee.

Aussi disponible en français

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i

INTRODUCTION 1

Report Structure............................................................................................................................................1

Summary Report ...................................................................................................................................1

Appendices............................................................................................................................................1

The Family Law Committee .........................................................................................................................2

THE CONSULTATION PROGRAM 3

Purpose of the Consultation ..........................................................................................................................3

Methodology.................................................................................................................................................3

Design of the Consultation Program .....................................................................................................3

Development and Distribution of the Consultation Document and Feedback Booklet ........................ 4

Development and Use of the Discussion Guide....................................................................................4

Receipt of Briefs and Letters.................................................................................................................4

Implementation of the Workshops........................................................................................................4

SUMMARY OF THE CONSULTATIONS: WORKSHOPS AND SUBMISSIONS 7

Best Interests of Children..............................................................................................................................7

Specifying Factors in the Divorce Act...................................................................................................8

Specific Factors.....................................................................................................................................9

The Opinion of Youth Participants .....................................................................................................14

Roles and Responsibilities of Parents .........................................................................................................17

Factors Enabling Good Parenting After Separation or Divorce..........................................................17

Awareness of and Improvements to Services .....................................................................................20

Using Terms Other Than Custody and Access....................................................................................24

Options for Legislative Terminology..................................................................................................27

Summary of Predominant Themes on Terminology ...........................................................................36

Family Violence..........................................................................................................................................38

Issues Facing Children ........................................................................................................................39

How Well Does the Family Law System Promote the Safety of Children and Others? .....................40

Terminology and Legislation: Messages and Specific Issues .............................................................41

Perspectives on the Five Legislative Options .....................................................................................46

Mechanisms for Ensuring Implementation of Legislation..................................................................49

Improvements to Services...................................................................................................................49

High Conflict Relationships........................................................................................................................54

Promoting the Best Interests of Children ............................................................................................54

Legislative Approaches.......................................................................................................................55

Legislative Options .............................................................................................................................56

Improvements to Services...................................................................................................................60

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

Children’s Perspectives...............................................................................................................................61

Taking Children’s Perspectives into Account.....................................................................................62

Should Children’s Perspectives be Better Incorporated? ....................................................................62

How to Incorporate Children’s Perspectives.......................................................................................64

Meeting Access Responsibilities ................................................................................................................66

Encouraging Parents to Meet Access Responsibilities .......................................................................67

Promoting Meeting Access Responsibilities Through the Law .......................................................... 68

Services to Support Meeting Access Responsibilities ........................................................................ 70

Child Support..............................................................................................................................................72

Child Support in Shared Custody Situations.......................................................................................73

Impact of Access Costs on Child Support Amounts...........................................................................76

Child Support for Children at or Over the Age of Majority................................................................ 78

Child Support Obligations of a Spouse Who Stands in Place of a Parent........................................... 80

SUMMARY OF THE CONSULTATIONS 82

Best Interests of Children............................................................................................................................82

Roles and Responsibilities of Parents .........................................................................................................83

Family Violence..........................................................................................................................................83

High Conflict Relationships........................................................................................................................84

Children’s Perspectives...............................................................................................................................84

Meeting Access Responsibilities ................................................................................................................85

Child Support..............................................................................................................................................85

Child Support in Shared Custody Situations.......................................................................................85

Impact of Access Costs on Child Support Amounts...........................................................................86

Child Support for Children at or Over the Age of Majority................................................................86

Aboriginal Perspectives ..............................................................................................................................86

Services.......................................................................................................................................................87

NEXT STEPS 88

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

APPENDIX A: REPORT ON YOUTH WORKSHOPS 91

APPENDIX B: REPORT ON ABORIGINAL WORKSHOP 107

APPENDIX C: REPORT ON PROVINCIAL AND TERRITORIAL WORKSHOPS 119

Alberta ......................................................................................................................................................119

British Columbia.......................................................................................................................................133

Manitoba ...................................................................................................................................................145

New Brunswick.........................................................................................................................................163

Newfoundland and Labrador ....................................................................................................................173

Northwest Territories ................................................................................................................................213

Nova Scotia...............................................................................................................................................233

Nunavut.....................................................................................................................................................243

Ontario ......................................................................................................................................................251

Prince Edward Island ................................................................................................................................275

Quebec ......................................................................................................................................................289

Saskatchewan............................................................................................................................................ 355

Yukon........................................................................................................................................................375

APPENDIX D: LIST OF BRIEFS AND BACKGROUND MATERIALS RECEIVED 383

REPORT ON FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL- TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

i

——

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The federal, provincial and territorial governments held nation-wide consultations

on custody, access and child support issues from early April to the end of

June 2001. Canadians with an interest in these issues contributed their views

through some 2,300 feedback booklets, 71 written submissions and 46 workshops,

all of which are summarized in this report. The results of the consultations, as

presented in this report, will be used to inform the Federal-Provincial-Territorial

Family Law Committee’s work on its Custody and Access Project as well as the

discussions of federal, provincial and territorial Ministers Responsible for Justice.

They will also provide valuable qualitative information on recurring issues and

themes for a report to Parliament on custody, access and child support to be tabled

by the federal Minister of Justice before May 2002.

The following topics were addressed during the consultations:

• best interests of the children;

• roles and responsibilities of parents after separation or divorce;

• family violence;

• high conflict relationships;

• children’s perspectives;

• meeting access responsibilities; and

• child support.

The key points raised by participants on each of these topics are described in the

following pages.

BEST INTERESTS OF CHILDREN

Respondents were asked to identify what children need when their parents separate

or divorce. They suggested the following needs:

• physical safety and emotional, psychological and financial security;

• as great a level of stability and consistency as possible during and after the

process of separation;

• their voices to be heard and their integrity to be respected;

REPORT ON FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL- TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

ii

——

• to not feel burdened with responsibility for the separation or for parents’

behaviour;

• to not participate in their parents’ dispute or in legal or court processes; and

• to feel that their particular cultural and developmental needs are being

considered.

Some respondents thought that children need to maintain contact with both parents

at all times. Other respondents were of the opinion that, in cases of high conflict

between parents or family violence, children’s needs are best met by limiting

contact with the aggressive or violent parent.

Those in favour of including in the Divorce Act a list of factors for determining

children’s best interests thought that it could provide useful guidance for judges

and parents to help ensure that they consider relevant concerns when making

decisions on custody and access. Those arguing against including a list of factors

said that such a list would exacerbate conflict and competition between parents.

They also feared that the use of a list would exclude the consideration of unlisted

factors and discourage assessment of the particular circumstances of each family

situation. Finally, others thought that establishing a list would neither make court

decisions more predictable nor reduce disputes.

With regard to support services, respondents often indicated that existing services

should be better publicized and made more accessible to all, regardless of gender or

location. According to these respondents, improvements to such services would

include the following characteristics:

• Better coordination between community and government services would

improve accessibility of services for children.

• A conciliatory approach would be preferable to resorting to the legal system.

• Information, education and counselling and other support services must be

readily available to help parents focus on their children’s needs.

• More community-based services and mediation services are required, and the

number of children’s advocates must be increased.

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF PARENTS

AFTER SEPARATION OR DIVORCE

In response to a question about what factors enable “good parenting,” respondents

identified a wide variety of issues relating to the parents themselves and their

relationship, the support offered to both parents by the legal system, and the various

support services in place.

REPORT ON FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL- TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

iii

——

Respondents stressed the need for improved educational services (for parents as

well as for the legal profession), support services (such as supervised access centres

or “parenting coordinators”) and legal aid services. To improve the effectiveness of

services, respondents suggested that services be offered in a more coordinated,

timely and accessible manner.

Participants were asked whether the terms custody and access, which are currently

used in the Divorce Act, should be changed. The main argument in favour of

changing the terminology is that the terms custody and access have negative

connotations of ownership and promote the concept of a “winner” and a “loser”,

which leads to an adversarial process and perpetuates a perceived anti-male bias in

the current system. Those opposed to changing the terminology maintained that it is

well understood by Canadians and within the legal system, that it is useful in

situations in which sole custody is in the best interests of the children (for example,

in situations of violence), and that resources would be required to define the new

terms.

Some respondents thought that narrowing the definition of custody and introducing

the term parental responsibility would be more appropriate. They felt that a more

neutral terminology would encourage parents to divide their responsibilities

themselves (without assuming a 50-50 split of responsibilities). Some respondents

voiced the following arguments against this proposal: the proposed terminology is

too vague and, therefore, may lead to greater conflict and litigation; and children

need to have only one primary caregiver, which the term parental responsibility

may preclude.

Those in favour of replacing current terminology with the term parental

responsibility highlighted the fact that the term emphasizes parents’ responsibilities

towards their children as opposed to parents’ rights. Some respondents suggested

that individual responsibilities must be detailed in the law; while others said such a

list of responsibilities would be counter-productive.

Those who preferred the option of replacing the current terminology with the term

shared parenting said that the presumption of shared parenting gives both parents

equal responsibility for parenting, promotes a low-conflict framework for

allocating parental responsibilities, and ensures that children have access to both

parents and extended family. Respondents who disagreed with this option took the

position that the shared parenting model is not always realistic, may have negative

effects on children (for example, when family violence is an issue), and does not

acknowledge situations in which a parent may not be fit nor willing to care for the

children.

REPORT ON FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL- TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

iv

——

FAMILY VIOLENCE

Several respondents indicated that family law legislation should contain three

points about family violence:

• a statement that the best interests of children are the first priority;

• a clear definition of violence (in particular, the scope of the definition); and

• an allocation of burden of proof (in particular, whether this should rest with the

alleged victim or with the alleged perpetrator, and what should be done in the

meantime to protect children).

On the other hand, others thought that the current legislation should not be

changed. Participants raised the following arguments, among others:

• Strong legislative and procedural processes are already in place to address

concerns of family violence. Violence is a factor that is currently carefully

considered in court through the “best interests” test;

• Highlighting family violence could lead to increased false allegations of

violence. This could lead to inadequate consideration of other factors of

significance to the best interest of children;

• Government involvement in resolving issues of family violence should be

minimal;

• It is more important to ensure affordable services (such as counselling or

supervised access) than focusing on making legislative changes.

Furthermore, some respondents mentioned the difficulty of attempting to define

violence correctly in legislation and that governments should develop awareness

programs and provide training on the realities of family violence to service

providers and the legal community (for example, judges).

With regard to the legislative options presented in the consultation document,

respondents differed about what is in the best interests of children. Some thought

that children’s safety should be the priority, while others insisted that the priority

was the children’s access to both parents. Those who gave priority to the safety of

the children supported limiting contact between the children and the violent parent

as well as the decisionmaking of this parent unless he or she could prove that such

a limit was not in the children’s best interests. Those who felt access to both

parents should be the priority supported a presumption of “maximum contact,”

except when there was proof that the parent had been violent towards the children.

REPORT ON FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL- TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

v

——

Some respondents suggested that the overall approach to services addressing the

needs of children in situations of family violence should be based on the following

principles: best interests of the children; prevention of violence; sensitivity to

cultural differences; ensuring safety; and gender sensitivity. Many people were of

the opinion that structural and organizational changes are needed to improve the

current provision of services, including the following:

• more community-based services;

• sufficient funding;

• improved coordination of services; and

• greater accessibility to services.

HIGH CONFLICT RELATIONSHIPS

Some respondents said that high conflict situations were, in fact, another form of

family violence. They felt that distinguishing between situations of high conflict

and those involving family violence implies that a certain level of violence is

acceptable. Other respondents thought that high conflict situations are a natural by-

product of the divorce process. They said that although parents may be in a high

conflict relationship it does not mean that they are not able to care for their

children.

Those respondents who agreed that the law should deal with the problem of high

conflict relationships generally supported a combination of options 2 and 3 or of

options 2 and 4 (from those presented in the consultation document). Both

combinations would result in a very detailed agreement about parenting

arrangements, which supporters felt would reduce the likelihood of further

litigation and conflict between the parents. The two combinations differ on whether

that agreement would be achieved through a mandatory dispute resolution process

(which some respondents felt would be ineffective in a high conflict situation) or

through the courts.

CHILDREN’S PERSPECTIVES

Young people were asked to discuss their views on whether children’s perspectives

should be considered during discussions on custody and access, and, if so, how this

should be done. Both the young people and other respondents indicated that

children’s perspectives are currently considered to varying degrees, depending on a

number of factors.

Some respondents thought that children should not be consulted because their

views would not be considered anyway, and that the emotional consequences

would be too great. Others added that very often children would not understand the

situation well enough to make a decision. According to some respondents,

REPORT ON FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL- TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

vi

——

children’s opinions, if they are considered, should not be the sole basis for

decisions that affect children.

Many young people thought that children should be better informed about their

parents’ difficult relationship but should remain outside their parents’ dispute and

should be consulted at the time of separation. Some women’s rights organizations

and some Aboriginal respondents echoed this position.

Some young people spoke in favour of the possibility of expressing their views to a

neutral third party (for example, a mediator). These participants also identified

factors that should determine children’s level of involvement: age; professional

support; ability to provide information; relationship with parents; and emotional

well-being. Special needs, the presence of family violence or high conflict

relationships, and cultural values should also be considered.

Several respondents emphasized the need to safeguard children’s well-being

throughout their participation in the decisionmaking process. This would involve

the following:

• adequate representation by a children’s advocate;

• protection from any repercussions from the parents; and

• information about the reasons for the decisions being made.

MEETING ACCESS RESPONSIBILITIES

Respondents said there are two main issues to be addressed with regard to meeting

access responsibilities: denial of access by the custodial parent; and non-exercise of

access. Respondents felt that both of these situations were equally detrimental to

children’s welfare, and proposed that tools such as parenting plans, parental

education and counselling be considered as ways to encourage parents to meet their

access responsibilities.

Respondents recognized that it would be very difficult to resolve the problem of

non-exercise of access through the law. They thought that forcing an uninterested

parent to have contact with his or her children would not be in the children’s best

interests and might even be dangerous.

Respondents did, however, feel that there were some areas in which legislation

could be useful in addressing the problem of denial of access, specifically, by

means of enforcement orders, alternatives to court-based solutions, and supervised

access centres.

REPORT ON FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL- TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

vii

——

CHILD SUPPORT

Respondents provided input on several questions concerning child support.

With regard to calculating child support amounts in shared custody situations, some

respondents raised concerns about time or cost being the sole determining factors.

Respondents supported transparent guidelines or a formula-based approach for

determining the amount of child support to be paid in shared custody situations.

With regard to unusually high and unusually low access costs, respondents thought

that both situations should be addressed in child support guidelines and legislation.

With regard to the payment of child support once children are at or over the age of

majority, some respondents favoured paying some or all of the child support

directly to the children, which would reassure the parent paying the support that the

money is being spent on the children. Other respondents were not in favour of

direct payment, pointing out that the custodial parent continues to have expenses

related to maintaining a home for the children, regardless of the children’s age.

PARTICIPANTS’ PERSPECTIVES

The consultations uncovered a wide range of views among Canadians based on

individual experience, professional opinion and the perspectives embraced by the

organizations participants represented. From these opinions, three recurring themes

emerged:

• many men’s organizations (and other non-custodial parent support groups)

supported implementing the recommendations of the Special Joint Committee

on Child Custody and Access;

• many women’s organizations argued that the consultation process and options

did not recognize gender issues and, therefore, that a gender analysis should take

place before proceeding;

• many professionals (e.g. lawyers and service providers) said that the term

parental responsibility had merit as a flexible option that could address many of

the concerns raised by other respondents, with or without changing existing

terminology in the area of custody and access.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

1

——

INTRODUCTION

This summary report was prepared by IER Planning, Research and Management

Services, which was retained to support and assist the nationwide federal-

provincial-territorial consultations on custody and access and child support. The

findings in this report will be used to inform the Federal-Provincial-Territorial

Family Law Committee’s discussions on its child custody and access project and

will form part of the background to the report to Parliament that the federal

Minister of Justice will table before May 2002.

The consultation sought specific comment on a consultation document developed

by the Family Law Committee, entitled Putting Children’s Interests First: Custody,

Access and Child Support in Canada. In a parallel process, workshops were held in

all provinces and territories in Canada, including specific workshops for Aboriginal

stakeholders and youth.

REPORT STRUCTURE

The report on the consultations comprises two main parts: the summary report and

the appendices.

Summary Report

This report summarizes comments on the options, key messages and

recommendations received from Canadians, and reflects their understanding of

laws and issues related to custody and access and child support in Canada.

As noted under “Methodology” below, the material summarized in this report was

provided through briefs, letters, feedback booklets and workshops. Because of the

nature of the consultation process and topics, comments in this report are not

attributed to any one person or organization.

Appendices

The appendices are separate reports summarizing the input received at workshops

for youth (Appendix A), for Aboriginal people (Appendix B) and in each province

and territory (Appendix C). Appendix D contains a list of written submissions and

explanatory material received by IER.

IER developed most of the appendices from notes taken at the workshops in each

province and territory, supported by notes from IER staff who attended each

session, with the exception of Nunavut. Some provinces and territories (namely

Quebec, Newfoundland and Northwest Territories) wrote their own report on the

consultations that took place and submitted it for inclusion here. The report on

youth was compiled by the facilitators of the youth workshops in Winnipeg and

Toronto, with support from facilitators of the youth workshops in Moose Jaw and

Montreal. Key findings from all these reports are included in the summary report.

This report is a

summary of the

results of nation-wide

consultations on

custody and access

and child support

issues in Canada.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

2

——

THE FAMILY LAW COMMITTEE

The Family Law Committee is a long-standing committee of federal, provincial and

territorial government officials who are well acquainted with family law. The

committee has a federal co-chair and a provincial co-chair and reports to the

federal, provincial and territorial deputy ministers responsible for justice issues.

The committee’s work supports and is approved by the Deputy Ministers and

Ministers responsible for Justice across Canada.

The Family Law Committee is reviewing legislation and services to find ways to

help families work out the best arrangements for children during and after

separation and divorce. It has adopted an integrated, child-focused approach to its

work. The Family Law Committee’s child custody and access project encompasses

research, analysis, and policy and program development among federal, provincial

and territorial policy advisors and service providers. This project is also looking at

the recommendations of the Special Joint Committee on Child Custody and Access.

The project is to be completed by spring 2002. The Family Law Committee

developed the consultation document to support the consultations on custody and

access and child support.

The Family Law

Committee is a long-

standing committee of

government officials.

Its work supports and

is approved by the

Deputy Ministers and

Ministers responsible

for Justice across

Canada.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

3

——

THE CONSULTATION PROGRAM

PURPOSE OF THE CONSULTATION

The purpose of the consultation was to seek advice, input and comments on options

related to custody and access and child support in support of the Family Law

Committee’s custody and access project.

METHODOLOGY

Key elements of the methodology for the consultations included the following:

• design of the consultation program;

• development and distribution of the consultation document and feedback

booklet;

• development and use of the workshop discussion guide;

• receipt of briefs and letters from individuals and groups; and

• implementation of the workshops in each province and territory.

Design of the Consultation Program

The Department of Justice Canada initiated a nationwide bidding process for a

contractor to help it, in collaboration with the Family Law Committee, design and

implement the consultations. IER, an independent consulting firm specializing in

consultation and communication since 1971, won the contract.

IER presented the Family Law Committee with several options for the design of the

consultation program. IER then helped develop a coordinated approach to the

workshops in each province and territory. This included writing a logistics guide

for the organization of the workshops, a facilitator manual for coordinated

facilitation of the discussion topics, and a discussion guide for facilitators and

participants at the workshops. More information on the discussion guide is

provided below (see “Development and Use of the Discussion Guide”). IER held

two facilitator training sessions, one in Prince Edward Island and one in British

Columbia, to coordinate the facilitation of the workshops.

The purpose of the

consultation was to

seek advice, input

and comments on

options related to

custody and access

and child support.

IER helped develop a

coordinated

approach to the

workshops in each

province and

territory.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

4

——

Development and Distribution of the Consultation Document and Feedback

Booklet

The Family Law Committee developed a consultation document entitled Putting

Children’s Interests First: Custody, Access and Child Support in Canada.

Approximately 10,000 consultation documents were distributed by the Department

of Justice Canada, the provinces and territories. Copies were also sent to members

of Parliament. The consultation document was also available on the Internet and on

request from the Department of Justice Canada. Each document included a

feedback booklet and a postage-paid envelope to make it easy for people to return

their comments. The document was also produced in Braille, and two such copies

were requested.

IER received 2,324 completed feedback booklets. The initial deadline for receiving

written comments was June 15, but this was extended to July 6. Approximately

55 percent of the booklets received contained identical answers. The key points in

the responses, whether submitted once or many times, are included in the main

report.

Development and Use of the Discussion Guide

IER developed a discussion guide based on the consultation document to introduce

in-person workshop participants to the workshop topics and the discussion

questions. There were two parts to the discussion guide: the first included the

custody and access topics to be discussed at the workshop; the other listed

government services available in each province and territory. The discussion guide

was produced in modules so that each province and territory could select topics for

discussion at the workshops and the appropriate listings of government services.

Receipt of Briefs and Letters

Many participants in the consultation program provided their comments on

custody, access and child support in the form of written submissions. A total of

71 submissions were received by the extended deadline of July 6. These

submissions were reviewed, and the key points are summarized in this report.

Written submissions received after July 6 were forwarded to the Department of

Justice Canada for information and are not included in this report. Appendix D lists

the titles and authors of all the written submissions.

Implementation of the Workshops

Workshops in the Provinces and Territories

In all but two provinces and territories, justice ministry officials invited the

participants, organized the workshops and arranged facilitation services.

For the workshops in Manitoba and Ontario, IER organized workshops, invited the

participants, and provided facilitation services when requested. IER developed

initial lists of potential participants with an interest in custody and access and child

support issues. These lists were expanded through referrals from initial contacts

The Family Law

Committee developed

a consultation

document entitled

Putting Children’s

Interests First:

Custody, Access and

Child Support in

Canada.

IER received 2,324

completed feedback

booklets.

A total of 71 written

submissions were

received.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

5

——

and from suggestions by provincial, territorial and federal officials. Names of

additional participants suggested by some organizations were included in the

invitations when it did not result in organizations having more than one

representative at each consultation. Potential participants were then contacted by

telephone and e-mail to determine interest and availability.

Between one and six workshops were held in each province and territory, for a total

of thirty-eight. Eight other workshops were held on youth and Aboriginal

perspectives; see below. Representatives from the federal government and the

provincial and territorial governments attended each of the sessions. Staff from IER

also attended the workshops, except in Nunavut.

Participants invited to the provincial and territorial workshops represented a range

of interests in custody and access and child support matters: social service;

education; enforcement; legal community; child welfare; women’s groups; men’s

groups; grandparents’ groups; and Aboriginal organizations, among others.

Approximately 750 people participated in the workshops. The organizations that

participated in the in-person workshops are listed in each provincial or territorial

report in Appendix C.

The workshops took place between April 10 and June 28, 2001. Each provincial

and territorial jurisdiction addressed the topic of roles and responsibilities of

parents. Other workshop topics were selected by each province and territory from

those listed in the consultation document, as follows:

• best interests of children;

• family violence;

• high conflict relationships;

• children’s perspectives; and

• meeting access responsibilities.

Some provinces and territories also held discussions on child support issues.

Workshops for Y outh

Seven workshops for youth were held: one organized by the Saskatchewan

government in Moose Jaw, and six organized by the Department of Justice Canada:

two in Winnipeg, two in Toronto and two in Montreal in June 2001. The 69 youth

participants ranged in age from 10 to 17 years. For the workshops organized by the

Department of Justice Canada, the participants were initially identified through

random calls by local market research firms, and then selected according to criteria

that ensured a range of age groups, and that gender, ethnicity and other factors were

considered. Appendix A reports on the youth consultation, including the selection

process and criteria.

There were seven

workshops for youth.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

6

——

In addition, workshops for youth organized by an independent firm were held in

Quebec City, Montreal and Trois-Rivières in May and June 2001. The results are

found in the report on the consultations in Quebec in Appendix C.

Workshop on Aboriginal Perspectives

A workshop was held in Ottawa to obtain Aboriginal perspectives on custody and

access and child support issues. The workshop included opening and closing

ceremonies led by an elder of the Bear Clan, and the workshop facilitators were

Aboriginal. The following topics were discussed in the workshop: custody and

access issues concerning Aboriginal peoples; best interests of children from the

Aboriginal perspective; and roles and responsibilities of parents. A total of

18 participants attended. Appendix B is a report on the workshop.

A workshop was held

in Ottawa to obtain

Aboriginal

perspectives on

custody and access

and child support

issues.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

7

——

SUMMARY OF THE CONSULTATIONS:

WORKSHOPS AND SUBMISSIONS

This section summarizes Canadians’ responses to the questions asked in the

consultation document. It includes input received through the in-person workshops

and written submissions (briefs and feedback booklets). The information presented

synthesizes the wide range of opinions put forward by Canadians on these topics.

BEST INTERESTS OF CHILDREN

In Canada, family laws relating to parenting decisions are based on the principle of

the “best interests of the child.” People making decisions that affect children during

and after separation and divorce must take children’s best interests into account.

Some, but not all, provincial and territorial laws list specific factors that parents are

to look at when making decisions about their children. These factors include

children’s ages and special needs, their relationships with the important people in

their lives, the role of extended family, cultural issues, the history of the parenting

of the children and future plans for them.

Currently, the federal Divorce Act does not set out factors that parents should

consider when determining the best interests of children. Some people think that it

should. A list of factors might educate people about the things that they should

consider when making decisions that affect their children.

There are varying opinions on this issue. Some say that listing factors would

neither increase the predictability of outcomes nor decrease litigation. In fact, in

comparing provinces and territories that have a list of factors with those that do not,

there is very little difference in the types of custody and access orders issued.

Adding a few key factors could be helpful, but having too many might make the list

too long and difficult to use.

Respondents were asked whether adding factors to the section of the Divorce Act

that covers “best interests of the child” would be helpful and, if so, what those

factors could be.

The topic of best interests of children was addressed with two questions:

• Would adding factors to the “best interests” section of the Divorce Act help

people make decisions about children that are in the children’s best interests?;

and

• If factors were to be specified, what should they be?

Respondents were

asked whether adding

factors to the section

of the Divorce Act

that covers the “best

interests of the child”

would be helpful and,

if so, what those

factors could be.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

8

——

Specifying Factors in the Divorce Act

There were a number of positions presented in favour of and against adding a list of

factors to the “best interests” section of the Divorce Act.

Reasons for Listing Factors

Some people suggested that federal legislation that identifies factors to be

considered by judges and others is desirable and an improvement in family law.

Listing factors in the legislation would do several things:

• greatly assist judges;

• provide guidance for divorcing parents who are developing their own parenting

arrangements on what factors they might consider when looking at their

children’s futures;

• ensure that all relevant concerns regarding the best interests of children are

considered in a systematic way within the decisionmaking process;

• compel parents and judges to consider a wider range of factors and family

situations when determining children’s futures; and

• dispel the mystery surrounding the rationale for decisions and instead promote

clear and traceable decisions, leading to better understanding by parents.

Furthermore, participants pointed out that the definition of the best interests of the

child has to recognize that the notion of the traditional family no longer applies to

all families and that different types of families need to be accepted without

stereotype.

Participants also suggested that it is important to harmonize federal legislation with

provincial and territorial legislation. This would reduce confusion by providing a

consistent framework for decisionmaking.

Reasons for Not Listing Factors

Some people did not agree that the Divorce Act should include a list of factors.

Their concerns included the following:

• The presence of legislated factors might limit the discretion of judges to deal

with the unique situations of divorcing couples;

• There is a risk that significant but unlisted factors would not be taken into

consideration;

• There could be problems deciding how to rate different factors for families

(e.g. cultural and economic differences);

Arguments in favour

of listing factors in

the Divorce Act.

Arguments against

listing factors in the

Divorce Act.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

9

——

• A checklist approach would mean that each factor could be evaluated without

full understanding of the children’s environment or what is at stake;

• Listing the factors might spark a more competitive or contentious discussion

between parents, inviting them to aggressively promote their position on each

factor; and

• Establishing a list would neither make court decisions more predictable nor

reduce disputes.

Some men’s and women’s advocacy groups said that the question of the rights of

custodial and non-custodial parents must be resolved before a meaningful

discussion can be had about factors affecting the best interests of children. The

women’s groups taking this position said that the mother’s role of nurturer and

primary caregiver should be acknowledged. The men’s groups taking this position

said that both parents should have the right to a shared or equal parenting role

(including equal time with their children and equal participation in

decisionmaking).

Other respondents proposed alternatives to listing all the factors, including these:

• a general definition of the best interests of the child, which could evolve over

time and is flexible and easily applied to individual situations;

• guidelines or principles in the Divorce Act that help ensure that children’s needs

and abilities are met; and

• a statement that it is in the children’s best interests that decisions about children

be made in an atmosphere of collaboration, respect and dialogue, rather than

conflict.

Specific Factors

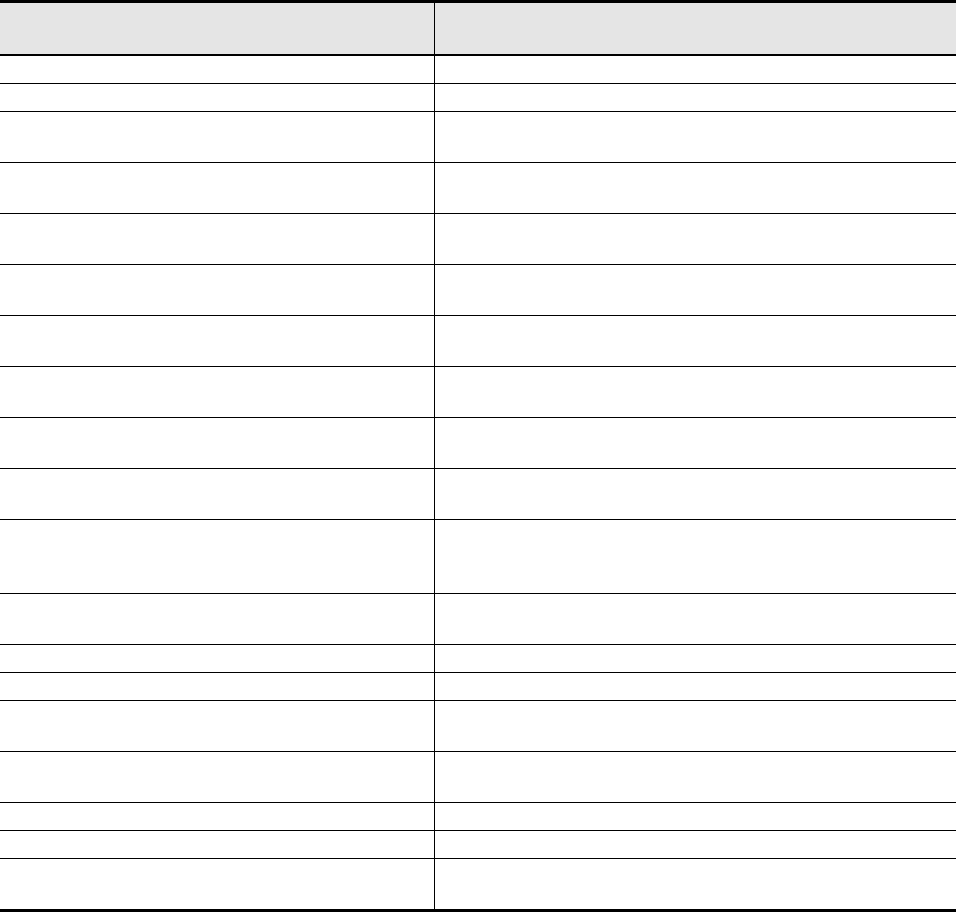

To identify factors that define the best interests of the child that might be included

in the federal legislation, respondents were first asked to identify the needs of

children when their parents divorce. Their responses formed the basis of the

discussion on factors that could be specified in the Divorce Act. A table

summarizing these factors is on pages 15 and 16.

Stability and Consistency

Although participants acknowledged that each family’s situation is unique, they

generally agreed that children need a safe, stable, healthy and loving environment

during separation and divorce. Specific factors mentioned included the following:

• Parents must show respect for their children;

• Parents must not involve or blame their children for the dissolution of the

marriage;

Some men’s and

women’s advocacy

groups said that the

question of the rights

of custodial and non-

custodial parents

must be resolved

before a meaningful

discussion can be had

about factors

affecting the “best

interests of children.”

Children need a safe,

stable, healthy and

loving environment

during separation

and divorce.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

10

——

• The children’s daily routine, standard of living and relations with the extended

family must continue both during and after separation;

• Both parents must have “rules” in their homes (there was disagreement about

whether these should be the same rules or whether each parent could have his or

her own);

• Children must have a clear idea about the time they will spend with each parent;

• Parents should inform children of the parenting arrangements ahead of time;

• Parents should follow through as much as possible with arrangements they have

made with the children; and

• Stability in the children’s lives outside of the family—in the community, schools

and day care—must be maintained.

Health and Safety

Participants strongly emphasized safety. Children must live in an environment that

is calm and free from conflict. However, participants disagreed on what safety

entails. Some people said that children’s safety refers to their whole environment:

physical, emotional, psychological and financial, as well as the assurance that basic

needs, such as housing and medical care, will be met. Other people focused on the

importance of keeping children out of any disagreements, conflict and, in some

cases, violence between parents.

When children’s safety is compromised, measures to protect children must be in

place and enforced. There was disagreement, however, about the types of measures

that are appropriate when abuse is alleged but has not yet been investigated.

Children Should Not Carry Any Burden

The children’s integrity—both respecting their lives and views and ensuring that

they do not feel the burden of responsibility for the separation or divorce—also

came up in discussion. Respondents felt that children’s burdens would be

minimized if the following occurred:

• parents communicated openly and honestly with their children throughout the

divorce process;

• children were heard and had the opportunity to express their own opinions

(issues related to children’s perspectives are discussed starting on page 61);

• appropriate services and intervention were available for children to help them

live with and adapt to the separation;

• parents ensured that their children do not take responsibility for their parents’

well-being;

Children must live in

an environment that

is calm and free from

conflict.

The children’s

integrity—both

respecting their own

lives and views and

ensuring that they do

not feel the burden of

responsibility for the

separation or

divorce—also came

up in discussion.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

11

——

• parents acknowledged that children need time to grieve for the separation of

their family;

• children were not made to be mediators or messengers, forced to report to and

from the other parent;

• children were given permission to love both parents without guilt or fear of

recrimination (therefore, it is important that parents refrain from commenting

negatively about the other parent in front of the children);

• children did not have to choose between parents; and

• children did not have to worry about adult problems, such as money or child

support.

Extended Family

Parents must allow their children to care for any new partners and their new

extended family when it is safe to do so and while respecting the importance of the

children’s ongoing contact with siblings and existing extended family. Extended

family members can provide the necessary support and continuity in children’s

lives; however, they must also be aware of children’s need for ongoing

communication and support, free from conflict. The Yukon Children’s Act was

held up as an example of how to address these issues in legislation. The Act has

been amended to include grandparents among those who can apply for custody of

and access to children. This change is especially important in the North because in

First Nations communities, grandparents are actively involved in raising their

grandchildren.

Protection from Conflict and the Court Process

Children should be protected as much as possible from ongoing participation in the

legal system, and should not be forced to take on adult responsibilities. It is vital

that parents not use children as leverage or “pawns” to gain control of the situation.

Children should be also protected from witnessing any kind of conflict or violence.

Cultural and Developmental Needs

Children’s ever-changing developmental needs are a factor, and it is important that

children develop positive self-esteem and their own cultural identity. Respondents

felt that children must have the opportunity to learn from both parents about their

cultural backgrounds. Respondents also mentioned that the concept of the “best

interests of the child” is foreign to many immigrant families, because their ideas

about children’s upbringing are often based on different cultural customs.

Parents must allow

their children to care

for any new partners

and their new

extended family while

respecting the

importance of the

children’s ongoing

contact with siblings

and existing extended

family.

Children should be

protected from

ongoing participation

in the legal system.

It is important that

children develop

positive self-esteem

and their own

cultural identity.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

12

——

Northern and Aboriginal Communities

Several factors were raised that deal specifically with the needs of children in

northern and Aboriginal communities:

• There is greater deference towards children in the North and they traditionally

have more input into where they go after divorce or separation;

• Many children are not registered at birth and have trouble throughout their lives

accessing resources;

• Traditionally, it is considered appropriate and better for children to reside with

their mother; and

• A large part of the population moves often, either to or from the North, which

can create problems for children when their parents separate or divorce. One

parent may decide he or she no longer wants or is able to remain in the North, or

he or she might be forced to leave to find work.

Parents’ Access

There were diverging views about parents’ access to children. While some people

said that parents must adhere strictly to the access arrangements, others felt that

there should be flexibility to change the agreement when necessary.

Some people said that children need “equal access” to and maximum contact with

both parents, unrelated to financial issues. These people said that in “normal” cases

(in which abuse does not exist), children want to be with both parents. Furthermore,

some respondents said that there should be a shared parenting arrangement unless

there was clear evidence that this would not be in the best interests of the children.

Other suggestions made in relation to access included the following:

• Both parents should be committed to staying geographically near one another to

enable children’s access to and involvement with both parents;

• Maximum contact must be balanced with the need to provide a stable home for

the children; and

• In joint custody arrangements, a certain amount of flexibility is required so both

parents can be responsive to children’s activities and needs.

Support Services

For children’s best interests to be met, the appropriate support services must be

available. Improvements and changes were suggested regarding legal, educational

and emotional support services, specifically that the various community and

government services need to be better coordinated to ensure all services are

accessible to children. The Child and Youth Network in Cape Breton was cited as

Strict adherence to

access agreements

versus flexibility.

Improvements and

changes were

suggested regarding

legal, educational

and emotional

support services.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

13

——

an example of this coordination. Adequate access to services in all communities—

urban, rural, northern and reserve—was also emphasized.

Respondents said that the family law system must be dedicated to the children’s

best interests. Such a system should do the following:

• emphasize a conciliatory approach over the current adversarial process;

• encourage parents to make decisions quickly, avoiding a lengthy process and

minimizing disruption of children’s routines;

• contain a “standard order” or “default position” to counteract parents’

unwillingness to make timely custody and access decisions (however, such a

temporary order would establish a status quo in the law, which may be unsafe

for some children or parents);

• provide adequate resources, such as sufficient legal aid, parental assessments

and children’s needs assessments, to ensure informed and effective

decisionmaking;

• be sensitive to cultural issues;

• acknowledge that the timing and deadlines associated with legal processes do

not take into account the inaccessibility of legal aid and support services for

many Aboriginal communities;

• provide children with a voice to express their views on time-sharing and

parenting arrangements (for example, through their own lawyer, counsellor,

social worker or elder);

• mandate a periodic review of the parenting arrangements to ensure that the best

interests of the children are still being met; and

• facilitate the mediation and settlement of parental break-up outside the courts.

With regard to educational services, respondents suggested changes to the school

curriculum that would support children, including the following:

• courses on separation and divorce issues; and

• proactive educational programs for children of separating parents so they can

understand relationships and develop life skills.

People also suggested programs to educate parents and service providers on the

impact of separation and divorce on children. These are discussed in more depth

below (see “Awareness of and Improvements to Services”).

Changes to the school

curriculum.

Programs to educate

parents and service

providers.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

14

——

With regard to emotional support, respondents made the following suggestions for

services:

• additional information resources (in the appropriate language) that would

support children;

• a mentoring program for children (either with children from intact families or, as

youth participants suggested, with children of divorced parents);

• support groups for children who relocate to another community and lose their

existing social circle;

• counselling and mediation for parents and children;

• community-based clinics and family conflict resolution services (such as the

pilot project in Durham Region in Ontario);

• profiling of families so they can be referred to agencies such as the Children’s

Aid Society (when necessary) and other services (such as counselling and

education) as needed to address the children’s needs;

• mandatory counselling for children who have been exposed to high levels of

conflict;

• efforts by parents to ensure that children feel secure in their homes, and do not

fear being “taken away” by social service agencies;

• the “circle” approach, which is a way to ensure equal balance of power between

service providers, families and elders when discussing and assessing children’s

best interests; and

• assurance that, for Aboriginal children, any psychological assessment or

therapeutic mediation involve an elder to ensure cultural differences are

acknowledged.

The Opinion of Youth Participants

Participants in the workshops described how parental separation and divorce affect

their lives. On the one hand, they identified their disapproval of parents who are

unable or unwilling to resolve their differences. As one participant explained, “I

still love my parents but I have to understand that’s how it is. It’s hard to respect

parents because of their behaviour.”

On the other hand, participants seemed to accept that not all relationships are

successful and that some do not continue. Many participants were able to identify

positive aspects of divorce, such as increasing one’s independence, learning from

mistakes and becoming a stronger person. They expressed concern that parents did

not always work hard enough on their relationships, both before and after the

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

15

——

divorce. Many of the youths acknowledged that it is now harder to trust adults.

Some participants were clearly burdened by their parents’ divorce and had assumed

or were given responsibilities beyond their years (e.g. involvement in financial

decisions). One participant advised the other youths, “You have to look after your

mother, because your dad’s not there anymore.”

Young people are looking to parents and policy makers to create effective and

responsive services that support children when parents no longer live together.

They expect child support obligations to be fulfilled. They want to learn skills that

will enable them to contribute to the decisionmaking process. They expect

professionals to be available, youth-oriented and responsive to their needs. They

worry about the future and their ability to be successful in relationships. They are

searching for effective role models and want parents to take more responsibility for

preparing them for adulthood.

More information on the results of the youth workshops can be found in

Appendix A.

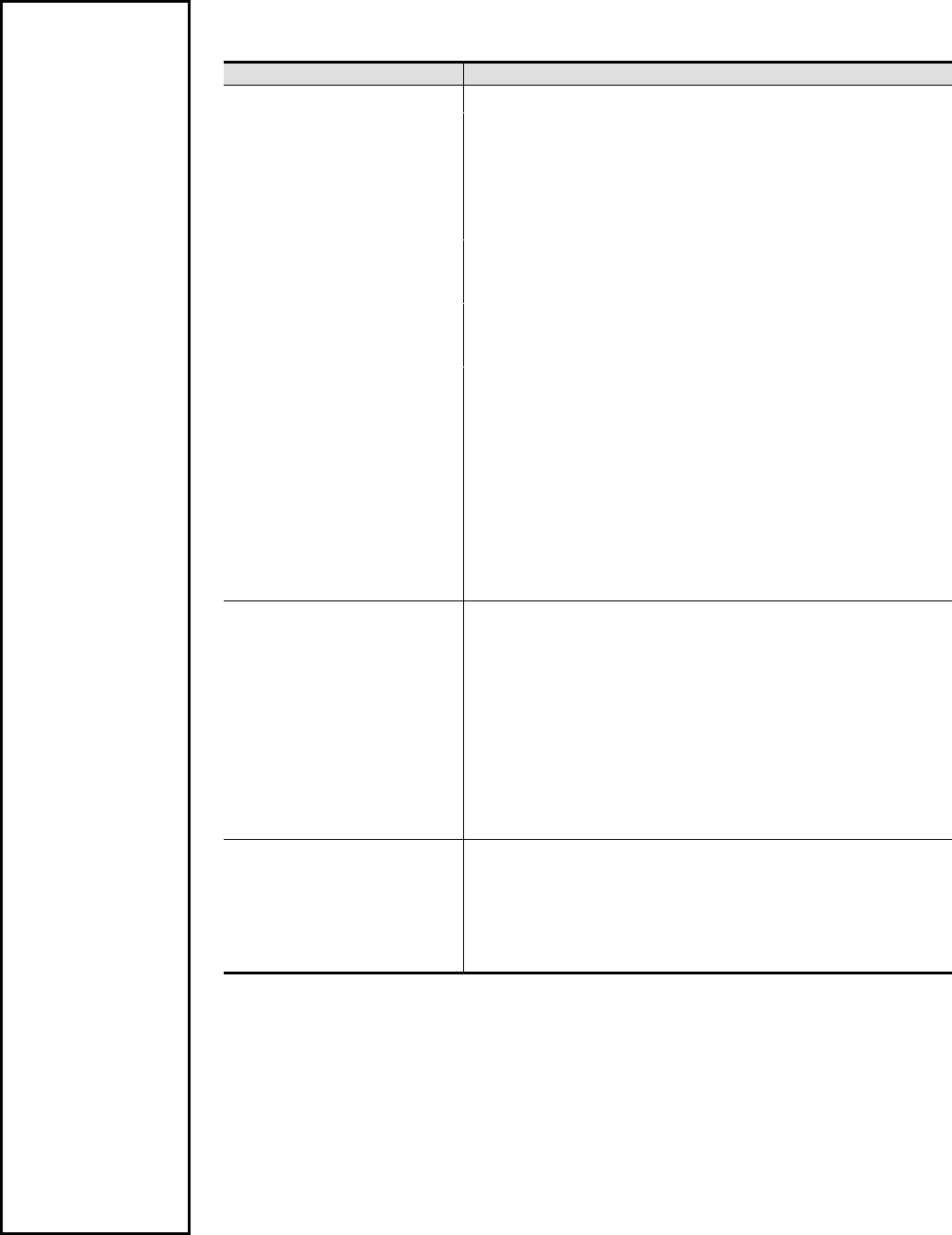

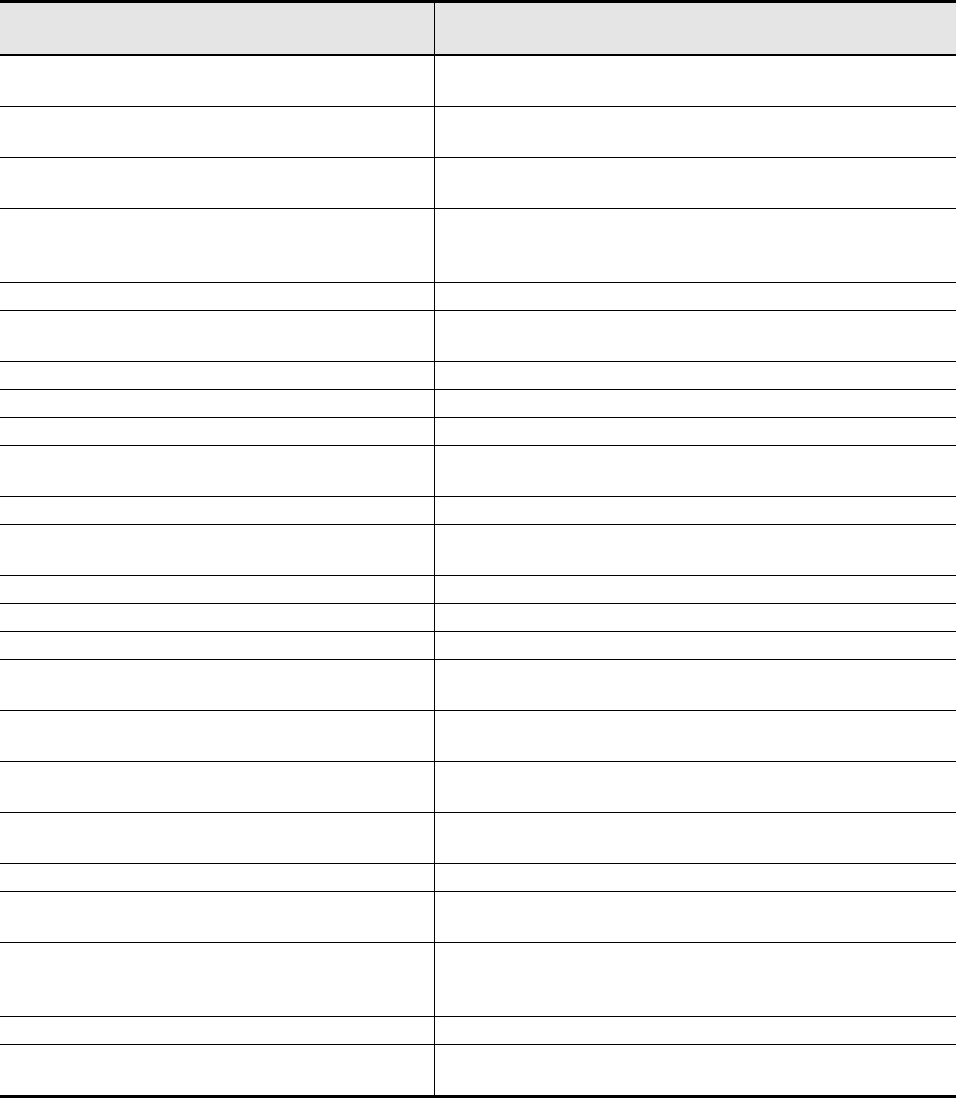

Table 1: Factors That Could be Included in the “Best Interests of the Child”

Section of the Divorce Act

Factors

Related to the

children themselves

Culture, ethnic and religious or spiritual background*

Language

Stability

Healthy and loving environment

Health*

Special needs*

Academic needs

Continuity of daily routine

Similar standard of living

Predictable time spent with both parents

Maintaining same school and day care

Freedom from conflict

Calm environment

Physical, emotional, psychological and financial security

Adequate housing and medical care

Views and preferences*

Culture and traditional knowledge (for Aboriginal children)

Remaining in current neighborhood

Close proximity to both parents

Not worrying about adult issues (e.g. money or child support)

Not forced to take on adult responsibilities (i.e. for siblings)

Continuation of ongoing activities

Age and stage of development*

Development of strong self-esteem

Not afraid of being “taken away” by social service agencies

Personality and ability to adjust*

Current and future educational requirements*

Young people are

looking to parents

and policy makers to

create effective and

responsive services

that support children

when parents no

longer live together.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

16

——

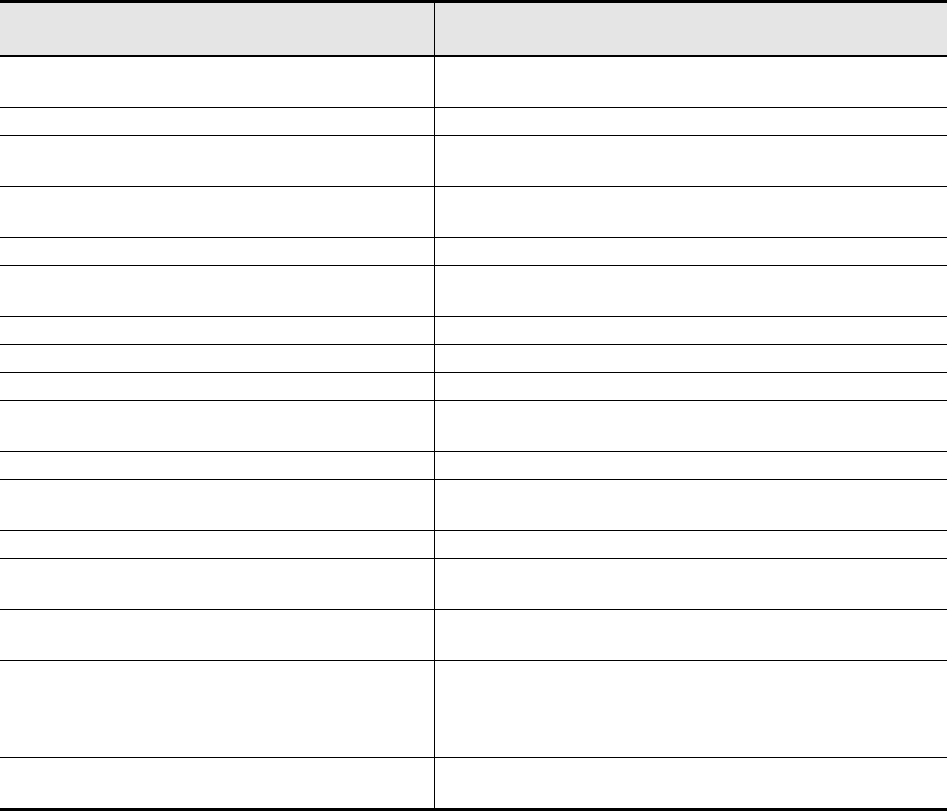

Table 1: Factors That Could be Included in the “Best Interests of the Child”

Section of the Divorce Act (cont’d)

Factors

Related to the

children’s

relationships with

others

Relationship with other members of the family*

Relationship with the wider community*

Relationship with friends

Relationship with siblings*

Relationship with parents*

Relationship with elders

Relationship with grandparents on both sides of the family

Relationship with any person involved in the children’s care and

upbringing*

History of children’s relationships

Equal access to both parents (when abuse is not an issue)

Ability to care for parents’ new partners and new extended family

Related to the

parenting of the

children in the past

Appropriate protective measures when abuse is alleged (not defined)

History of the parenting of the children*

History or pattern of violence

Past conduct of parents that is relevant to their parenting abilities*

Related to the future

of the children

Periodic review of parenting arrangements to ensure they are still meeting

the best interests of the children

Ability of parents to meet ongoing and developmental needs*

Parent’s ability to form and follow through with a plan for his or her

children

Ability of parents and other involved people to cooperate*

Potential for future conflict*

Potential for future violence affecting the children*

Additional factors

to be considered

Parental respect

Parents keeping children out of interparental conflict and violence

Parents not blaming children or making them feel responsible for the divorce

Parents maintaining similar rules for the children and respecting each other’s

rules

Parents respecting arrangements to spend time with children

Parents not using children as messengers or mediators or as pawns or tools

to influence the other parent

Parents communicating openly and honestly with the children

Supervised access that meets California’s standards on safety

Protection for children during participation in legal process

Child advocate (e.g. lawyer, counsellor, social worker or elder)

Appropriate and accessible services for children

Appropriate and accessible services for parents

Parents committed to staying in geographical proximity to facilitate access

Parental flexibility so that children’s needs and activities come first

Legislation that promotes and facilitates mediation rather than the court

system for settling disputes about custody and access

* Identifies factors highlighted in the consultation document and agreed with by some participants.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

17

——

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF PARENTS

This topic looks at how best to define parental responsibilities after a separation or

divorce to ensure that the best interests of children are considered.

When parents separate or divorce, they must work out how they will continue to

carry out their parenting roles and responsibilities. Most separating and divorcing

couples are able to agree and work out their own parenting arrangements. Others

find it difficult to agree on such issues as where the children will live, and who will

be responsible for their day-to-day needs, schooling, religious education and sports

activities. It is even harder for parents to make decisions about their children when

there is mental illness, substance abuse or violence between the parents or directed

at the children.

The following questions addressed the topic of roles and responsibilities:

• What factors enable good parenting after separation or divorce?;

• How aware are you of existing services in your community? How could these

services be improved?; and

• Would using terms other than custody and access make a difference in the way

parenting arrangements are determined after separation or divorce?

Respondents also considered the following five options for changing the

terminology used in legislation relating to separation and divorce:

• keeping the current legislative terminology;

• clarifying the current legislative terminology by defining custody broadly;

• clarifying the current legislative terminology by defining custody narrowly and

introducing the new term and concept of parental responsibility;

• replacing the current legislative terminology with the new term and concept of

parental responsibility; and

• replacing the current legislative terminology with the new term and concept of

shared parenting.

Factors Enabling Good Parenting After Separation or Divorce

To identify factors enabling good parenting after separation, some people began by

defining good parenting. They felt that children’s needs would remain much the

same after a separation or divorce—therefore, parents’ responsibility to fulfil those

needs would remain unchanged. These respondents acknowledged, however, that

some parents would be taking on different roles (in some cases, roles that are new

What is the best way

to define parental

responsibilities after

a separation or

divorce to ensure that

the best interests of

children are

considered?

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

18

——

to them; in other cases, having more responsibility) in fulfilling those needs, and

that they would need to develop new skills.

Some women’s groups said that a thorough gender analysis of parenting issues is

required to ensure that family laws are congruent with Canada’s national and

international commitments to gender-based policies and laws, and that the results

of that analysis would be a basis for good post-divorce parenting.

Some advocates for non-custodial parents said that implementing the

recommendations of the Special Joint Committee on Child Custody and Access

would enable good post-divorce parenting.

Many factors that enable good parenting after separation were identified. They

relate to three areas:

• the parents themselves;

• legislative support; and

• other support available to parents.

Respondents raised many points relating to the parents’ role in meeting their

children’s needs, and what those needs would be during separation and divorce.

These points are addressed starting on page 7.

A table summarizing all of the factors can be found at the end of this chapter

(page 37).

The Parents

With regard to the parents themselves, respondents identified many factors that

would enable good parenting after divorce:

• communication;

• cooperation;

• maturity;

• flexibility;

• willingness to keep the peace;

• ability to come to an agreement (either through mediation or through the court

system) about roles and responsibilities;

• willingness to respect the agreement;

Factors that enable

good parenting are

related to:

• the parents;

• legislative support;

and

• other support.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

19

——

• ability to separate personal issues (dealing with former and current relationships)

from issues that touch on their children’s well-being;

• ability to take responsibility for mistakes and willingness to try again;

• acknowledgment of the existence of cultural differences in child-rearing

practices;

• validation of the parenting abilities of men, as well as of women with disabilities

and gays and lesbian women;

• acknowledgment that a parent is not replaceable by a new partner or extended

family;

• consideration of the specific needs of Aboriginal Canadians (a more in-depth

look at the concerns of Aboriginal Canadians is provided in Appendix B); and

• acceptance of children having access to both parents.

Legislative Support

Some people said that a legal system that recognized both parents as equally

capable and needed by the children would support good parenting. Others said that

the law must take into account women’s social and economic disadvantage, and

argued that the image of the father as an ideal nurturing parent is often inaccurate.

Other points made with regard to the law were the following:

• The law must be flexible enough to recognize that some parents are not

interested in parenting, and that forcing them to be involved in their children’s

lives would be detrimental to the children;

• The legislation must specify the need for a parenting plan that explicitly sets out

each parent’s roles and responsibilities. This would help parents agree and

understand their responsibilities;

• Child support should begin as soon as possible and the parent receiving support

should be open about how he or she uses child support funds (a more in-depth

discussion on child support can be found starting on page 72); and

• Both parents should have and be made to promote adequate access to the

children (a more in-depth discussion on access can be found on page 66).

Other Support Available to Parents

Some respondents said that good parenting implies that parents must seek out

external support for themselves (and for their children) during separation and

divorce. Respondents’ suggestions about the types of services that would be helpful

are discussed below.

REPORT ON FEDERAL

-

PROVINCIAL

-

TERRITORIAL CONSULTATIONS

——

20

——

Awareness of and Improvements to Services

People were aware to varying degrees of the services available in their community.

Most felt that those services are not well publicized, nor do they adequately meet

the needs of parents during separation or divorce.

However, the opposing view was also expressed. Some people said that, as people

enter freely into marriages, they are solely responsible for their own well-being